On the thirteenth day of November in the year of our Lord 1988, the Murder, She Wrote episode Snow White, Blood Red aired. It was the fourth episode of the fifth season, and it’s one of my all-time favorites. (Last week’s episode was Mr. Penroy’s Vacation.)

Jessica has come to the mountains in order to enjoy a ski vacation with her nephew, Grady, who has not yet arrived. (This is merely a setup; Grady is not in this episode.)

The episode starts out on a foreboding note. A figure in a red ski jacket (who turns out to be Jessica) is skiing down the slopes as opening credits and ominous music play, then another skier in a white jacket begins to follow her.

At the bottom we discover that it was only a friend of hers named Johnny.

They joke a bit about Jessica being out of practice. (Johnny said she skied rather well, and, indeed, the stunt double we watched ski down the slopes did look to be in good practice.) It then comes up that there’s a big snowstorm expected the next day which will prevent all skiing, which Jessica takes relief at as she expects to pay for her heightened activity today. It’s a decent working-in of the upcoming plot point of the storm, but I’m not sure it’s really necessary. Storms, as acts of God, do not require foreshadowing in a mystery story.

It comes out that Johnny, as well as many other people present, are hopefuls for the US world cup ski team. There is one person present who has already made it, a fellow by the name of Gunnar Tilstrom. Johnny then excuses himself to help a cute young woman having trouble attaching her boots to her skis and the scene shifts to inside the pro shop.

The woman on the left is Anne. The man is Mike. They’re married and own the place. Mike is reminding Anne that she has to keep track of the inventory and she angrily replies that she made a mistake and asks how long he’s going to keep berating her. It’s an overreaction to his gentle tone, which suggests that she’s over-sensitive for some reason.

Jessica then walks in and witnesses a bit of the fight. She’s there to pick up something she ordered, which came in about an hour ago. As Anne gets the box, Jessica notices the crossbow on the wall:

Jessica remarks on it and Anne jokes that they use it to shoot beginners who clog up the expert course.

Jessica’s order turns out to be a blue ski suit she’s bought for Grady as a present, and remarks that the entire vacation is a present to him as she hasn’t seen him for three months.

The phone rings and Anne acts about as guilty as humanly possible, saying it would be better if the caller called back later. Mike comes over and takes the phone and asks if it’s Gunnar, but the person on the other end hangs up. Jessica asks if the coat can be put on her bill and high-tails it out of there, while Anne asks Mike how he could humiliate her like that and he replies that he was about to ask her the same thing. I guess we’ve found out why she’s over-sensitive to criticism.

We then cut to the bar, where we see Gunnar returning a landline telephone he borrowed to make the call.

We then cut over to a young woman named Pamela who is about to join Gunnar, having watched his disappointment as he handed back the telephone.

“Pitty, Gunnar. The old Swedish charm’s beginning to fail you,” she purrs in a delightful posh British accent.

There is some banter, but it turns out that she represents a ski product company which has an endorsement deal with Gunnar that she negotiated, and she remonstrates with him because she’s heard rumors that he won’t compete in the world cup. He explains that he’s won plenty of things before now and is pushing thirty years old and could end up crippled like Mike and have to spend the rest of his years running a ski resort like Mike. (Interestingly, the actor, Eric Allan Cramer, was 26 at the time the episode aired, making this a rare case of playing older. Fun fact: five years later Cramer would play Little John in the Mel Brooks movie Robin Hood: Men In Tights)

Meanwhile, Gunnar still has some skills, such as attracting women, and he sees himself marrying a rich widow who hasn’t been too ravished by the passage of time. Pamela counters that she heard he doesn’t confine himself to widows, and offers as evidence the rumor that a month ago he had an adventure in Tahoe was with the wife of a vindictive gangster.

Gunnar tells Pamela, basically, that he’s sorry for her that she was enough of a sucker to believe in him but that doesn’t alter his plans. Pamela leaves, disappointed, while Gunnar smiles.

Next, after an establishing shot of the ski slopes, we meet Gunnar’s coach, Karl.

He just spoke to Pamela and is concerned that Gunnar isn’t going to enter the world cup. They’ve worked together for two years on this! Gunnar says that he hasn’t decided what he’s going to do, but whatever it is, it will be without Karl. Karl grabs Gunnar’s arm and says, “You need me!” Gunnar shoves him to the ground and replies, “I need no one, least of all, you.”

I think we’ve got a decent number of suspects planted, now.

We now shift to evening in the hotel restaurant. Pamela is talking to a young skier named Larry McIvor.

He’d love to endorse her products, but he wonders what she needs him for since she has a contract with Gunnar. She likens the business world to a downhill course laced with rocks. He’s her insurance policy in case something goes wrong. He golly gosh sure could use the money ma’am, and proposes that they sleep on it. When Pamela raises her eyebrows, he’s deeply embarrassed and tries to assure her that’s not what he meant. Pamela smiles at his naive wholesomeness and says that he really is a delight, and offers her hand. They shake and the camera moves on to a new couple who Jessica runs into.

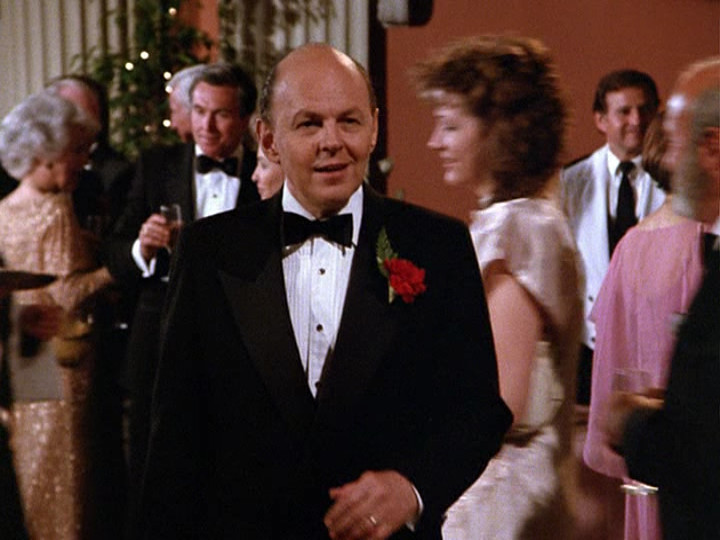

They’re husband and wife. His name is Ed McMasters, hers is Sylvia, and they’re from New York City. He invites Jessica to join them for dinner, “if you don’t mind eating with a cop.” She replies, “Not at all. They’re some of my favorite people.”

They talk over dinner for a bit, then at the end of the song that was playing the lead singer welcomes everyone to the Sable Mountain lodge and then calls out some of the world-class skiers present. “I don’t have to tell you, they stand to win a few gold medals at the next world-cup meet.” I wonder if they would have had to pay money to be able to say, “the winter Olympics.”

Anyway, they put the spotlight on the various people that he calls out for applause, and this results in everyone seeing who Gunnar was having dinner with.

Anne makes the best of this, then the camera gives a closeup of Anne picking up a highly distinctive gold lighter. These kind of closeups tell us that the thing in the center of the camera is important, so take a good look.

She looks around and here eye catches her husband staring at her from right behind Jessica, who looks and sees it. He walks off and the scene changes to outside, in the morning at first light. The storm has started and the snow is falling, but Gunnar is going for a ski.

As he’s going down on the slopes we see a crossbow raised. We then see the view through the crossbow’s scope and the crosshairs take aim at Gunnar. Right as he jumps a small rise the bolt finds its way home and Gunnar falls. He rolls to a stop, dead.

The camera fades to black and we go to our first commercial break.

When we come back from commercial break, Jessica is looking outside as a weather report says that the storm is looking to be far worse than feared and roads are becoming impassible. She walks down into the crowded lobby with her suitcases and meets Pamela, who says, “welcome to Bedlam. They say it’s going to be an hour but I suspect it’s going to be a lot longer than that.”

They’re not explicit but I suspect that everyone wants to leave because the storm has made skiing too dangerous. I’m not sure if that’s really a thing at mountain ski resorts, but it is at this one.

The van to drive people down the mountain and into town has temporarily broken, btw, and the scene shifts to Larry trying to help Mike with it. He pronounced the fuel line frozen and it is possible that the pump has gone bad too. (I’m a bit suspicious of this diagnosis since since the freezing point of gasoline is around -100F.) Mike asks Larry if he can fix it and Larry isn’t sure. Then Johnny walks in and brings the news that Gunnar has been found, dead, by some dumb teenagers who were skiing in the storm.

The scene shifts to the pro shop where the crossbow and all of its bolts is missing. The glass was shattered and a uniformed security guard reports that the back door was smashed in. Mike says that they need to get the cops up here but Anne walks in and says that there’s no way that’s going to happen. All of the roads are closed and will be until the storm lets up.

The scene shifts to Jessica’s room, where Mike and Anne ask her to investigate the death. People are beginning to panic and the appearance of something being done will help keep them calm. Jessica points out that they have a policeman staying with them—Lt. McMasters. Anne shakes her heard. The McMasters left early this morning, driving off before the storm hit.

Jessica doesn’t know what she can do but to the great relief of Mike and Anne, she agrees that whatever it is, she will do it.

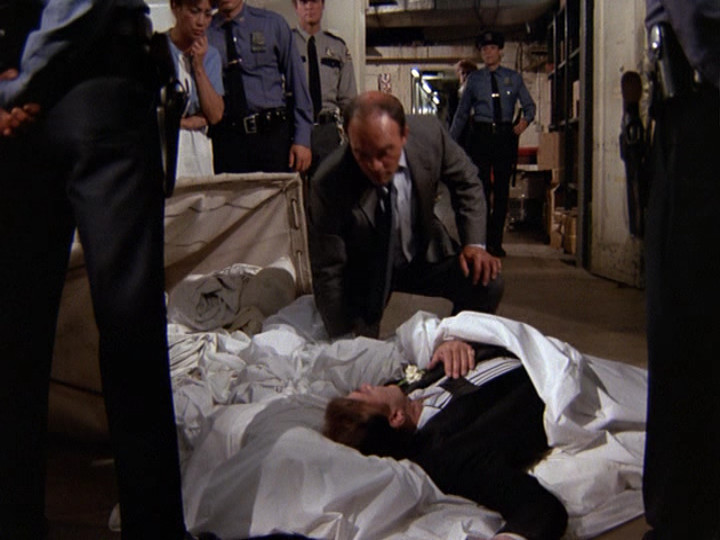

The scene shifts to her taking a look at the body.

The man standing with her is a doctor. Dr. Lewis. He objects that he is a gynecologist, not a forensic pathologist, but Jessica merely answers that necessity creates strange bedfellows.

Ed McMasters then walks in through the curtain and explains that they ran into a snow bank “about the size of the Chrysler building” and turned around. He looks at the body and asks Jessica for her opinion. Jessica tries to turn the case over to him but he demurs and agrees only that he will help her. He leaves, then Dr. Lewis asks if he can go and Jessica gives him permission.

She then begins to look through Gunnar’s jacket. She finds a room key, specifically room 301. She ponders the meaning of this as a mournful clarinet considers the question with her.

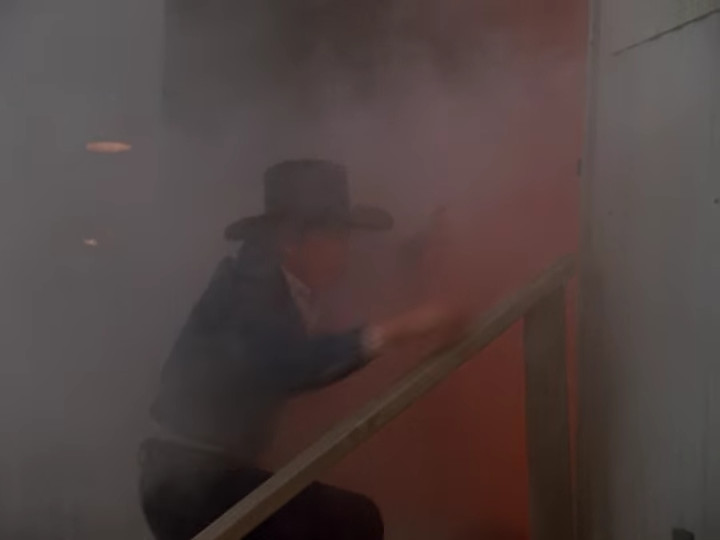

The scene then shifts to Jessica coming into the main room from outside. One of the things that’s done very well in this episode is visually suggesting the strength of the storm.

Still images only partially convey how inhospitable it is outside. Part of it is the difficulty people have in opening doors and the speed with which they come in and get the door closed again. The episode does a good job of showing how much everyone is at the mercy of the storm.

Anne stops Jessica and gives her a clue. After he left a phone message came in for Gunnar. “Urgent. Call me. (702) 555-0980. Vicki.” Jessica recognizes 702 as a Nevada number. She goes to her room and calls the number. A tough-sounding male voice answers and says, “Tartaglia residence.” Jessica asks to speak to Vicki and the voice replies, “Mrs. Tartaglia isn’t here at the moment. Who’s calling?” The tough voice is insistent on asking the question, “Who is this?” when Jessica doesn’t answer. Instead, she just hangs up the phone and picks up the room key that had been in Gunnar’s pocket.

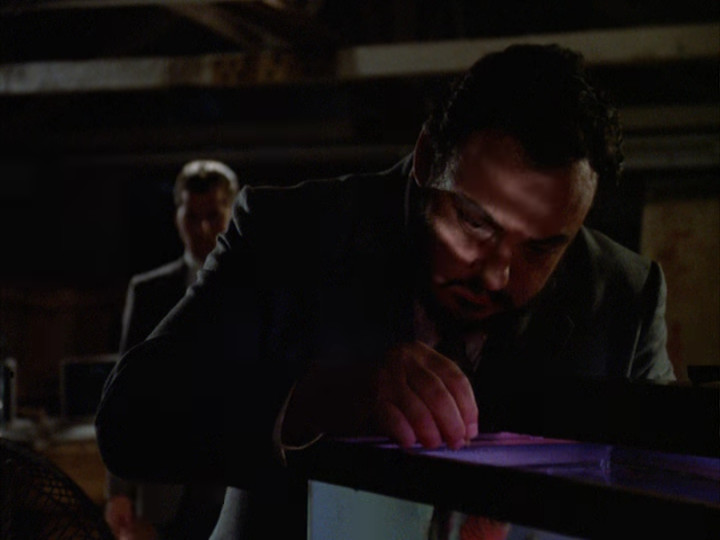

We then see Mike go into a dark room and begin looking for something.

Jessica walks out and shows him Anne’s golden cat lighter. Mike assures Jessica that Anne didn’t kill Gunnar. He left around 6am and Anne left around 7am. Mike knows because he was in an empty room at the end of the corridor watching.

These are the facts salient to the mystery; there is some interesting characterization where Mike explains that he and Ann were engaged prior to the accident which crippled him and while Anne went through with the marriage, he couldn’t bring himself to believe that she really loved him for him, rather than for the athlete he had been. This drove them apart, and you can see that he regrets it, giving some hope for the couple.

The scene shifts to a bunch of young men who are all, I assume, hopefuls for the world cup team who are drinking and sharing raucous memories of Gunnar. Larry gets up and excuses himself because he can’t drink and be merry with Gunnar dead.

Jessica walks up to Lt. McMasters, who watched the scene, and asks him what just happened (she saw Larry walking off looking upset). He replies, “I don’t know. I think it’s an Irish wake.”

Jessica then asks him if he’s made any progress on the murder weapon, but he hasn’t. Anne isn’t keen on a room-by-room search since everyone is already on edge. Neither of them point it out, but it would be a bit far-fetched for the crossbow to be in someone’s room, anyway. When you have the great outdoors to hide something in, it’s a far more sensible choice than storing it in a place which is tied to oneself.

Jessica then spies Pamela and joins her.

Pamela wastes little time in saying that she barely knew Gunnar and had no reason to kill him. Backing off from the abruptness, this turns into a conversation about Gunnar and how the list of people who wanted to kill him was long, though he could turn on the charm when he wanted to. She runs off a list of Gunnar’s flirtations with women that made the tabloids, including the one where he took up with the wife of a mobster and barely made it out of town with his life. This catches Jessica’s attention. She then asks Pamela why she sounds so bitter and Pamela admits that Gunnar was about to ruin the $3M endorsement contract with his womanizing.

Then scene then changes to a storage room where ominous music plays as gloved hands uncover the crossbow and pick up an arrow, showing it off to the camera.

Then we fade to black and go to the midpoint commercial break.

When we come back from commercial break, pamela is working out on an exercise bicycle while larry is doing overhead press on a weight machine. After a few seconds of introductory noises to let people hurry back from the bathroom, Larry says, “Maybe I’m just a dumb farm boy, but where I come from people have respect for the dead.”

Pamela tries to comfort him, saying that they didn’t mean harm and tragedy affects people differently. He’s in no mood for it, though, an accuses her of being there to make sure he will sign the contract. She denies it and he walks off to the locker room. Then Karl the trainer walks in and drunkenly accuses her of murdering Gunnar and threatens to kill her if he finds out he’s right.

After this threat session, Pamela goes to the woman’s locker room where, to her surprise, she hears the shower running. She sees clothes on the ground and, going to inspect them, finds them soaked with blood. She then goes into the shower room and finds Larry’s corpse, dripping blood, hung by the neck with a rope tied to the shower head, the water running over him. As you might imagine, the music is extremely tense. This is probably the most dramatically tense scene that’s been in a Murder, She Wrote episode. The tension is especially heightened by the fact that the murderer had to be close by since there wasn’t much time for the crime to be committed.

Pamela does the sensible thing and screams as loud as she possibly can. (That’s not a joke. This is a situation for attracting as much attention as humanly possible.)

The scene changes to her in her bedroom with Jessica. She is distraught, wondering who could possibly want to have killed such a nice kid. Lt. McMasters then walks in and says that, as near as they can figure—the gynecologist is a bit outside of his field of expertise—Larry was knocked unconscious in the men’s locker room, dragged to the women’s locker room, stabbed with an arrow, stripped, and hung up in the shower. Jessica says that this makes no sense and McMasters replies that (of course it makes no sense) they’re dealing with a luny, a certified hazel nut.

Anne comes into the room to say that there’s more bad news—the phone lines are down. They can keep up internal communications with their generator, but they are completely cut off from the civilized world.

Jessica asks if Sylvia (Lt McMasters’ wife) can stay with Pamela for the time being. She saw a vehicle with a CB radio in it—red, with a Massachusetts license plate—and she thinks that they should try very hard to get in touch with the police. Anne says that she’ll try to find out who owns it. McMasters says that he’s going to talk to the Norwegian ski coach, who seems not entirely right in the head.

In the next scene Jessica and Mike Lowry go to the red vehicle and call the Sheriff. They manage to report the second murder, but the Sheriff says that the roads are impossible and the helicopter can’t fly in this storm. They’ve got to hang on. Then everything goes to static for some reason which isn’t obvious but doies at least get us out of the conversation.

Mike and Jessica retreat to the pro shop, where Mike laments that this could destroy their business, into which they invested every cent they had.

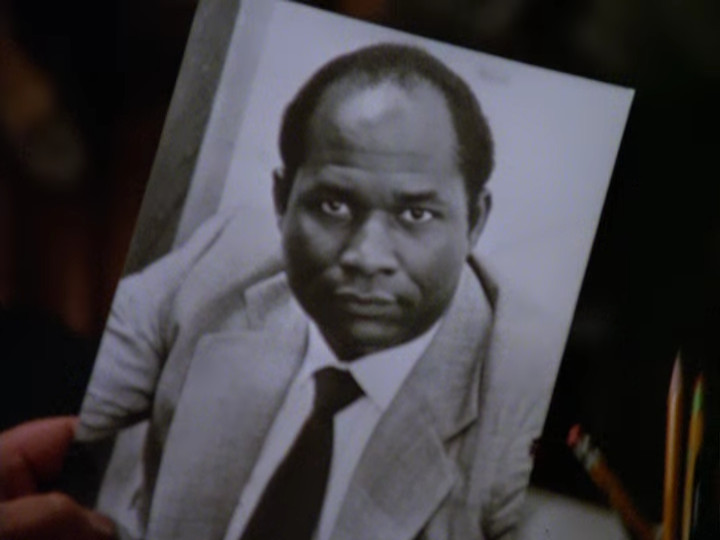

Jessica then notices the photograph of the last US World Cup team and asks if it was Mike’s idea to invite everyone up. The people in the picture are Gunnar, Larry, Johnny, and Mike (before his accident). Now two of the men in the photograph are dead. Jessica doesn’t know what it means, but there must be some reason for these killings.

Then they hear a crash and begin to investigate. As they do, Johnny comes through the door, his left arm bleeding.

In the next scene Johnny is in bed, the gynecologist tending to his wound.

At first blush the wound looks a bit low, but it could possiby be an attempt to stab Jonny in the heart. Johnny says that he was grabbed from behind and stabbed. Lt. McMasters says that they found another arrow nearby on the floor. Johnny didn’t see who it was, not even a sleeve. He fell to the ground and passed out, then woke up when he heard Jessica and Mike.

In the hall the gynecologist remarks that he used to think his practice was dull and repetitive, but has never been so eager to get back to his dull, boring routine in his life. He then quickly walks off.

Lt. McMasters remarks that he can’t blame the good doctor. It’s not much of a vacation to have some screwball going around trying to knock off the next world cup ski team.

Jessica is not so sure. The doctor said that the wound was superficial. Perhaps Johnny stabbed himself to divert suspicion?

McMasters thinks it unlikely. Jessica has done some checking up and Johnny is good but not that good; with Gunnar and Larry out of the way he’s got a much better chance of making the team. McMasters says that it’s a flimsy motive for murder, but Jessica counters that she’s heard worse.

Jessica then says that there is a third possibility—that Gunnar was the only real target. The killer probably planned to hit and run but got stuck in the snowstorm and had to create a smoke screen. McMasters says that this third one is a hell of a theory. Jessica replies that theories are easy to come by, the truth is much harder. She then says that they better hope that the weather clears up so that the police can come in the morning and take the investigation over from them.

The storm, however, rages through the night.

A few hours later Jessica, in bed, receives a call from a panicked Sylvia McMasters. With the sound of sleigh bells jingling in the background she asks if Ed is there with Jessica. Jessica, who was nearly asleep, says that he isn’t. Ed got a call a few minutes ago and rushed out. She doesn’t know who the call was from, but Ed took his gun. Jessica tells her to stay calm and that she’ll try to find Ed.

Jessica puts on her coat and braves the storm, looking for Ed.

She checks the ski shop but it’s locked. As she does Ed pops out from behind the building with his gun pointed at her and tells her to freeze. After she identifies herself he explains that some guy with a muffled voice called him and said to meet him outside the ski shop because he had information about the case. It sounded like a trap to him so he hid himself and waited.

As they talk a crossbow aims at them from the car barn and then fires, but misses, hitting the wall behind them. As they try to spot where the shot came from, the sound of a motor roars and a ski-mobile drives out of the car barn. McMasters orders the driver to stop, then fires three shots at him. The driver runs up a snow bank and topples over. They rush up and it’s Karl, the ski instructor, dead. Beside him lays the crossbow with two arrows left in its quiver.

The scene fades to black and we go to the final commercial break.

When we come back, Jessica is examining Karl’s ski jacket while Ed is telling Mike and Anne that he got the feeling, when Gunnar was pushing Karl around, that something was going to snap in the big trainer.

Mike says that it’s hard to believe, since Karl was like a father to them.

A phone call comes in with the news that the phone lines are back in operation. Ed is delighted by the news and looks forward to going home to NY. He says he’s going back to the lodge and asks Jessica if she’s coiming, but she’s nowhere to be found.

Outside Jessica is standing with Karl’s coat as the gynecologist comes running up. He begs her to promise that this is the last time she will press him into service as an amateur coroner. She asks if he got “them”, and he replies that he did. While surgery on corpses is not his long suit, he does believe that he extracted the bullets with a minimum of damage. Jessica looks at the bag he handed her and proclaims them two .38 caliber bullets, but did they come from the same gun?

The gynecologist doesn’t understand. He thought it was known that Karl was shot by Lt. McMasters. Jessica replies, “yes, but was he also shot by someone else?” The gynecologist looks confused, then horrified, then says, “You know, I’m afraid that if I ask you what you mean by that, you’re liable to tell me.” Without giving her the opportunity to say anything, he then very politely wishers her a good day and leaves, saying that he’s giving up skiing for something less rigorous, such as needle-point.

Jessica smiles, then goes into the car-barn and looks around. She then notices the jingle-bells on the wall next ot the telephone by the door.

Jessica then catches Sylvia on her way to meet Ed, who is warming up the car. Jessica says that they need to talk. Jessica is surprised that Ed wants to go home so soon and Sylvia explains that she’s anxious to get back to her cat. Ed then walks up and says that they have a busted fuel line, so will be stuck for a while. Jessica then invites Ed to have a seat, saying that there’s been a development.

Jessica then reveals that Karl didn’t kill anyone, he was murdered like the rest. There were two bullets in Karl, but only one of them struck him when he was alive. (If you recall the picture of his jacket, there was only one bullet hole with blood on it. Jessica then shows a second bullet hole in the jacket which we couldn’t see earlier because there’s no blood on it.) When the police check the ballistics, they’re going to find that both bullets came from the same gun. Moreover, they’re going to find that there is no Ed McMasters who works for the NYPD. Also, it was Sylvia who fired the crossbow at them; Jessica heard the sleigh bells in the background of the telephone call and didn’t think about it until she saw the sleigh bells hanging up next to the phone in the barn, but they place Sylvia not in her room, but in the barn. Also, another question is why, having killed Gunnar, didn’t the killer leave? The only people who tried to leave were the McMasters, who only came back because the road was impassable.

Jessica surmises that he was hired by Tartaglia to take vengeance on Gunnar and got trapped by the snowstorm. The rest of the killings were a cover-up when they couldn’t get away.

As the McMasters indignantly rise to leave we can hear the sound of a helicopter overhead and two security guards come out and detain the McMasters at gunpoint. When they clearly give up trying to escape, Jessica turns to Anne, who had just announced that the police have arrived, and we go to credits.

As I said at the outset, this is one of my favorite episodes. It’s tightly plotted with good characters and an intriguing mystery. By means of a powerful act of nature we have a closed cast of characters. The ongoing murders adds tension and makes the threat of the killer being loose present, while it also creates new clues as well as new things for them to fit into, creating satisfying complexity.

That is not to say that this episode is perfect. Like all the works of man it does have mistakes. For example, we see Jessica packed and ready to leave before Grady even shows up. It’s also a bit weird that Vicki left a message for Gunnar asking him to call her at a phone number that could easily get her husband. I’m not sure what her alternative would be since this was long before cell phones and she probably didn’t have a private phone line, but it’s still a bit unlikely. Also… actually, that’s about the only mistakes which comes to mind, and the first one doesn’t even matter because the plot only needed her to be in the lobby, which required no excuse anyway, and the second one could have been a slightly different message and serve the same purpose. This may be one of the reasons I like this episode so much.

Getting back to what this episode does well, we have a good setup which introduces a large but manageable cast of characters. I think that part of what keeps the large cast manageable is that they fall into several categories. We have the owners, the adjuncts to the ski team (the business woman and trainer), and some fellow guests. This is not the only approach, of course. The best alternative I know of is to give every character a hook to make remembering them easy. That said, this is an excellent approach and gives us manageable complexity.

Another great point is the economy of the setup. We get introduced to everyone, but we also have our corpse before we go to the first commercial break. This balance maximizes the mystery involved. If we were introduced to fewer people, we would have no scope for speculation. If we waited too much longer, we would need some kind of story that would compete for time with the mystery. This point is probably specific to the short-story form (which TV resembles more than it does novels), but it’s worth bearing in mind.

Next on the list of great things about this episode is the snow storm. It is a wonderful complication in the story, both helping and hindering the murderer and the detective alike. It brings in the eternal theme of how man is subject to nature, for all of our technological mastery. It also removes the possibility for modern forensic evidence, turning the mystery into more of a classic and making it more accessible. We all have wits, we do not all have forensic tools.

The gynecologist who is brought in to do the medical work has a real function but also brings in a touch of comic relief which balances out the threat of a killer on the loose who is willing to kill again. This is part of the general excellent pacing, where moments of examination and detection alternate with moments of tension and the killer acting.

The murderer is also well done in this episode. “Ed McMasters” pretending to be a New York City cop is a good way to divert suspicion from himself, but if you pay attention he does play it in a way that’s cagey and not comfortable with the role. He will happily drop the name of recognizable places (like the Major Deegan Expressway), but he mostly refuses to actually do anything that would require the knowledge of how to do real policework. Even when he does, he makes his actions ineffective. Tasked with finding the crossbow, he proposes a room-to-room search which he knows that Anne and Mike will object to and which wouldn’t do any good anyway, while looking like he’s trying.

The one part where he really slipped up in a way that doesn’t make a lot of sense to have slipped up was in actually shooting Karl’s corpse on the snowmobile. There was no reason for him to actually aim at the corpse and he had to know that a bullet which didn’t cause any bleeding would have had to be suspicious. There are two reasonable ways to explain this, though. The first is that he had to be aiming at approximately the right place because Jessica was watching him and he got unlucky and hit the corpse when he meant to miss it. It is not easy to put your bullets where you mean to with a handgun, so this could simply have been, as the kids these days would say, a “skill issue.” The other explanation is that he thought that the most convincing thing to Jessica would be method acting—to actually try to do the thing he was pretending to do—and he expected to fool her long enough to drive away once the roads were clear and then “Ed McMasters” would disappear and it wouldn’t matter that the coroner would discover that Karl was shot after he was dead. And to be fair to this second possibility, the only reason he didn’t escape was because Jessica was quick witted enough to examine the corpse and figure out what it meant.

This episode was just great from start to finish.

In next week’s episode we’re off to the mountains of West Virginia for Coal Miner’s Slaughter.

You must be logged in to post a comment.