Much of what drives the plot of a murder mystery are the problems with a murderer who wishes to avoid capture has to solve. In no particular order, the big ones are:

- Finding an opportunity to commit the murder

- Planning how to commit the murder

- Acquiring the tools necessary for the murder

- Committing the murder without (living) witnesses

- If possible, having an alibi for the time of the murder

- Disposing of the murder weapon

- Disposing of the corpse (I’m including making it look like accident/suicide here)

(Some of these problems are really alternatives to each other; for example if one has an alibi for the time of the murder, one doesn’t need to bother with disposing of the body. If one can acquire the murder weapon in an untraceable way, one can leave it next to the corpse with a label “murder weapon” helpfully attached to it. Etc.)

In writing a murder mystery, these are the questions the writer needs to answer and—at least the way I work—before writing the actual mystery. Actually, let me back up for a second and explain by way of my theory of murder mysteries:

A murder mysteries is actually two stories: a drama told backwards, and a detective story told forwards.

I think it’s fine to write a murder mystery by the seat of one’s pants as long as it’s only the detective story one is “pantsing”. If you’ve written the drama (the murderer’s story) ahead of time, you can’t get into too much of a mess with the detective story. Where people go wrong is in not having first figured out the drama in its natural order so that they can gradually tell it backwards. (NOTE: there will be people who can successfully write murder mysteries in a completely different way. I’m not trying to lay down laws everyone must follow.)

That’s what I mean by needing to figure out the murderer’s solution to his intrinsic problems first. Once you’ve figured out how the murderer has planned his murder, you can then work out how the murder actually happened, at which point you now have a coherent story for the detective to detect. I find this order of doing things very helpful for two main reasons:

- This mirrors reality; it’s the order in which murders actually do happen. This means that there’s precedent for it being a workable system.

- One has complete freedom for the first decisions one makes. And it’s in the murder itself where plot holds are the most damaging to a murder mystery. Thus starting here gives one the fewest temptations to try to hide a plot hole in order to preserve what’s already been done.

This also lets you decide ahead of time, in a coherent way, what mistakes the murderer made (i.e. what evidence they left), so that you know where to direct your detective to look.

Types of Murder Weapons

So, the question I want to consider is how the murderer acquires the murder weapon. There are several categories which each have their advantages and their shortcomings:

- Ready to hand

- Store-bought

- Home-made

A ready-to-hand murder weapon, such as a kitchen knife used to murder someone in the kitchen, has the benefit of being untraceable, since there is an obvious explanation for what the kitchen knife was doing there. The downside is that such things are unreliable and so unlikely to be in a planned murder. (Of course, one can always abscond with the knife beforehand then bring it so that it looks like it was snatched up in the heat of the moment.) Ready-to-hand weapons are also very likely to be simple—knives, pokers, hammers, etc. People very rarely leave loaded guns, crossbows and bolts, etc. lying about. This means that ready-to-hand weapons will require one to get very close to the victim and use a great deal of physical force. This eliminates squeamish murderers. And most modern people are pretty squeamish.

A store-bought murder weapon is likely to be in good working order and quite possibly useful for killing at a distance and without much force. The downside is that they are—at least in theory—traceable. Guns, crossbows, etc. have serial numbers. Shop keepers have memories and many big box stores have comprehensive video surveillance. Acquiring these things in an untraceable way can be done, but it takes far more work and premeditation, since the best bet here will be to buy them on the secondary market, in cash, months or better yet years before the murder. This requires a very patient—or lucky—murderer.

Home-made murder weapons offer a good compromise between ready-to-hand and store-bought. Building supplies like plywood, hinges, rubber bands, and so on are basically untraceable. And there are a ton of very deadly weapons one could very realistically make. If you don’t believe me, just watch a few episodes of The Slingshot Channel. The downside here is that one requires a fairly competent murderer with at least a few tools. The problem this introduces is one of personality: people who are patient and good at problem solving just don’t seem like the murdering sort. However much of a problem the victim is, there’s probably also a non-lethal way around the problem they pose.

Accomplices Make Everything Easier

One practical way around most of the problems brought up in the murder weapon section is an accomplice. Even better for the problem of murder weapon acquisition is the anonymous accomplice. As long as the murder weapon isn’t directly traceable to a name (i.e. isn’t a new gun/crossbow recently bought at a gun/bow shop), this will greatly obfuscate the trail of the weapon. If the detective doesn’t know whose footsteps to retrace, he will have a very hard time retracing them.

An anonymous accomplice can also go a long way in solving the problems of personality introduced by the choice of a murder weapon. Two people can be more patient than one, an accomplice who wouldn’t murder anyone himself might still help a lover or friend to buy or make a weapon, and so on.

(In fact, the ability for two people to have two personalities is sometimes revealed in just this way—the detective is talking about the contradictions in the murderer’s behavior and someone says, “It’s like our murderer is two different people… wait a minute!”)

Of course, this introduces its own set of problems since now the relationship must be explained. I think that the most typical motivations for the assistance are:

- Romantic interest

- Financial interest

Though this makes sense since they are the two big motivations for nearly everything and especially for nearly everything which is really bad. The other big motivation in human life is religious zeal, and while you probably could come up with a story in which a radical Muslim murders a Jew out of religious zeal, it would be hard to come up with a story in which he wanted to conceal it (though you could have friends do that over his objections) and in the current environment I doubt that such a story would be well received.

There is another way in which accomplices make things easier, though: being twice as many people they make twice as many mistakes—that is, they leave twice as many clues. Worse yet from the perspective of the murderer and better yet from the perspective of the detective, they can have the motivation to double-cross each other.

As with all solutions to a problem in a murder mystery, an accomplice solves some problems and causes others. This is why it’s better in real life to always do right, of course, because then all of your problems will at least be good problems to have, but in fiction it’s what has made mystery such an enduring genre.

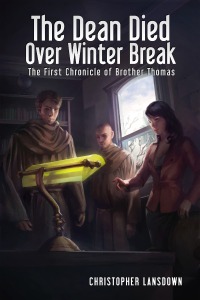

If you enjoy murder mysteries, please consider checking out my murder mystery, The Dean Died Over Winter Break.

You must be logged in to post a comment.