On the twentieth day of November in the year of our Lord 1988 the Murder, She Wrote episode Coal Miner’s Slaughter first aired. (Last week’s episode was Snow White, Blood Red.)

Set in rural West Virginia it’s in a small town where the major employer is the Colton Mining Company, which mines for coal. The episode opens at the Coal Miner’s Shindig, where a banner proclaims that the shindig is celebrating “Top Productivity.”

The camera pans over many people dancing to fiddle music, until it finally comes to rest on three people.

The older man on the right is Tyler Morgan. The man in the middle is his son, Reese Morgan, and he hates everything about this shindig, declaring it to be a waste of good company money. The woman is Nora Morgan. She is Tyler’s husband and Reese’s mother. From everything he says, they seem to have done a terrible job raising him.

The shindig is Tyler’s way of getting the men to accept a work speedup. Reese thinks that they should instead use computers to run the company, which would save them 20%. Tyler answers that he ran the company at a profit for thirty years, not by using computers, but by using his brain, and he’s going to keep it that way until they carry him out feet-first.

I don’t know whether they’re going to carry this through, but they’re setting up a John Henry type story of man vs. machine. It’s a very unrealistic man-vs-machine scenario. Computers, and especially the computers of the late 1980s, could not run a mine in any meaningful sense. What they could do is a whole lot of calculations. The labor that they would replace would have been done, not by the wise old man, but by a group of clerks whose names he probably didn’t know because he treated them, insofar as he could, like machines. The flip side of this is that the old man’s only real objection to computers would be their cost and reliability. The John Henry story they’re setting up is less John Henry vs. the spike driving machine and more John Henry who wanted to keep using a rock to drive spikes rather than upgrading to a hammer.

That said, realism is, of course, not the point. Rather, this is setting up a favorite theme of Murder, She Wrote: that old things are still valuable.

The issue with bringing computers into a business, apart from their expense and reliability, is that they are specialized tools which most people are not familiar with because they are new tools. Older people will have developed considerable skills with tools that are used differently—slide rules, desk calculators, binders of paper, etc. The new tools require different skills and so the older people will feel like their built-up skill’s value has become diminished (because it had). This has some unfortunate side-effects, though in reality it mostly made people uncomfortable for a year or two and then they became more productive with the new tools. There did become something of a class of maintenance workers for the new machines which were not needed for the old tools, just as the advent of cars created the job of car mechanic which did not exist in the age of horses. This did also create a feeling of dependency which many found unwelcome. Again, though, in practice people got used to this very quickly since almost none of them did their own plumbing or their own electrical work, and they owned cars which (in the 1980s) most of them took to mechanics to keep in working order. The modern world is highly interdependent because of all of the specialized tools that we have, and that does come with tradeoffs. They are, for the most part, livable tradeoffs. Civilization has always involved interdependence and it was no less doable to run away from civilization and live off of squirrel stew in the mountains in the 1980s than it was in the 1680s.

Murder, She Wrote did not address the real concerns of people actually doing the work, though. It addressed the concerns of people who saw this coming in their future or else (judging by the denture and term life insurance commercials which tended to play at commercial breaks) had retired and would never be taking the trouble to learn the new ways because they were never again going to do that work. Portraying computers as something that replaced human beings’ humanity, rather than low-level clerks drudgery, speaks to those concerns far more symbolically.

Anyway, Tyler walks off and Reese remarks to his mother that his father can’t die soon enough to suit his tastes. His mother rebukes him, saying that he owes his father respect. Reese replies by asking what kind of respect his father showed his mother, cheating on her all these years?

They’re certainly planting the motives thick for the old man’s death.

Taylor gets up and makes a speech, thanking everyone for coming, saying that the mine has been extremely profitable, and that what’s good for the mine is good for the miners. When he says this last part, a woman calls out, “That’s a lie and you know it!”

(It’s good to see that shoulder pads are still alive and well in 1988.)

She walks forward. He says, “I don’t believe we’ve met,” and she replies, “Actually, we have. Ten years ago, at my father’s funeral.” Her name is Molly Connors.

Tyler lays the southern stuff on thick, “Joe’s little girl? Well. Well. Well. You certainly have turned into a right fine filly.”

They talk back and forth a bit, but the upshot is she’s just passed the bar exam and her first case is to prove that he killed her father.

He replies that it will be quite hard to prove what never happened, especially from the inside of a jail cell, and directs the Sheriff to arrest her for trespassing on private property by attending a private party at a private venue to which she was not invited.

She says that he’ll never make this stick. He says maybe so and maybe not, but it might take a while to find out. (The judge is fishing at Tyler’s private fishing lodge and while Tyler will give the judge a call, if the trout are biting, the judge may well refuse to come back early from his vacation.)

As the Sheriff is taking Molly out of his car next to the police station, her grandfather (name of Eben) shows up and demands her release.

The Sheriff refuses. Eben goes for his shotgun but the Sheriff tells him, at gunpoint, to not pick it up. Molly pleads that she’ll be alright. She is entitled to a phone call and she knows someone who will help.

That someone is, of course, Jessica.

She arrives by bus, presumably the next day.

The next scene is the Sheriff talking with Molly; he offers her the advice not to fight fights she can’t win. She tries to accuse him of following his own advice, but he maintains that he does his best to uphold the law. He then opens the cell and tells her to get going as her bail has been paid in person.

(Obviously, this aspect of getting the legal system wrong is probably pure convenience, but for the record: bail is set by a judge at the defendant’s initial arraignment (which is required to take place within 48 hours of arrest or, if the arrest was on a weekend, within 72 hours). Bail is not set by Sheriffs or by a standard schedule. With the judge out of town, it would not be possible for Molly’s bail to have been set, so Jessica could not possibly bail her out.)

They do some chit-chatting to establish that they know each other (she was one of Jessica’s brightest protegés), then leave the Sheriff’s office. On the way out they run into Carlton Reid.

He came to bail her out as well. He’s the local miner’s union representative. He’s mighty glad to see that she’s out.

Tyler shows up at this exact moment and walks over and politely tells Molly that he seems to have underestimated her resourcefulness. This is a bit odd because all he really wanted was for her to stop interrupting the shindig, but whatever. I guess his villain nob needs to be turned up to eleven.

He then looks disapprovingly at Jessica and says, “I’m not sure about the wisdom of bringin’ a stranger in on something that’s none of her affair.” I’m not really clear on how Molly isn’t effectively a stranger since she was last here as a young child.

Jessica objects to this on the grounds that she and Molly aren’t strangers. I suppose she’s deliberately missing the point for some reason that’s not immediately obvious.

Tyler replies that it’s good that they’re so close since Eben’s place is hardly big enough for him and Molly. A young boy then offers that Jessica can stay with “us.” The camera then pans over to them.

The boy’s name is Travis and his mother is Bridie Harmon. They own a boarding house up the road. Rooms are $10 a day, meals are extra, and she locks up at 11:00pm. Jessica accepts. As Bridie tries to leave she has to call Travis several times because he’s busy having a staring contest with Tyler.

After they leave, Tyler bids Jessica welcome to Colton, then walks off and the scene shifts to dinner at Eben’s house. Jessica compliments the cooking and they reminisce about how Molly’s mother helped with the PTA and when Molly was in Jessica’s class, lugging around a huge book of Shakespeare. Apparently she and her mother moved to Cabot Cove after her father died. From West Virgina to Cabot Cove is quite a move, though it’s later explained that this was because her mother had kin in Maine. Anyway, the big Shakespeare book was the one thing of Molly’s father that she brought with her to Maine. We also get the detail that everyone in town knows that the explosion which killed Molly’s father was no accident (according to Eben).

Next we see Tyler receiving a phone call from an unnamed caller. Tyler recognizes the caller, though, as he says, “I thought I’d be hearing from you.” He then accepts an appointment to meet the caller at the cabin in half an hour. After the caller hangs up he thinks that Nora is listening in on the phone again, though when he asks if that’s her listening in, the phone just clicks. He then puts on his coat and leaves his house.

Then we see Molly dropping Jessica off at the boarding house. After she says goodbye Bridie asks if Jessica needs anything else because she’d like to lock up and get to bed. A minute later, Jessica goes to close the window and sees Bridie, outside, putting on a coat and covertly hurrying off somewhere.

Over at the cabin, we see the shadow of someone with a gun walking along.

The mysterious figure looks in the window and sees Tyler putting logs on the fire. It puts the handgun away and then slowly opens the door and takes a rifle from a rifle stand next to the door, aims at tyler, cocks, and shoots. We get an exterior shot of the cabin in the storm for a moment, then fade to black and go to commercial.

It’s pretty irresponsible for the rifles to be kept loaded in the rifle stand, but I suppose that was mostly just to save the time of creeping around and finding the ammunition and loading the rifle.

We come back from commercial to a bright and cheerful day.

After a few seconds of panning the camera to allow people to get back from the bathroom, Jessica walks along a bridge. When she gets to the other end Tyler’s son, Reese, tells her, at gun point, to stop moving. The scene then shifts to inside of the cabin where the Sheriff asks Jessica whether it’s a bit early for a city woman to be prowling about and she replies that she wouldn’t know, being from a small town, herself.

Apparently Jessica was walking to Eben’s house and took the wrong path, bringing her onto Morgan land. The Sheriff tells Reese that he can handle it alone and doesn’t take no for an answer, so Reese leaves. Jessica catches on that Tyler is dead and begins asking about it. The Sheriff says that, from the condition of the body, he died somewhere between 11:00 and 11:30 last night, but he’ll know more when the county boys in Yanceyville get done with him. He’s got plenty of ideas for who killed Tyler but no evidence to back up any of them.

He asks Jessica where she was between 11:00 and 11:30 last night. She tells him that she was in bed then sleeping, but would be hard-pressed to prove it. The Sheriff tells her to not worry about it since she doesn’t seem like the kind of woman to kill a man she barely knew and moreover she looks about as handy with a gun as he is with knitting needles. She asks why he asked where she was if she didn’t need an alibi, and he replies that he was hoping she might be able to supply an alibi for someone who does need one.

So far, the Sheriff is my favorite character in this episode, by far.

The Sheriff and Jessica go to Eben’s house, where Molly is surprised that Tyler is dead and Eben merely calls it hill justice. The Sheriff points out that the law calls it murder and he needs to know where they were. Molly got a flat tired on the way home from dropping Jessica off and so she didn’t get home until 11:30. Eben stayed put the whole night.

The scene then shifts to town, where Jessica and Molly come out of some building. Carlton Reid comes up and offers to give them a lift home. With the way tongues are wagging they’re likely to run into trouble if they stay. Molly will not be intimidated, though, and, spotting Mrs. Morgan and Reese, goes up and gives her condolences. These are about as well received as you might imagine, given that the Morgans believe she killed their husband/father.

Jessica and Carlton come up to try to make matters worse, Jessica in a somewhat conciliatory tone and Carlton in a far more aggressive tone (he all but accuses Reese of killing his father).

The Sheriff interrupts this to bring the news that he found Tyler’s rifle in molly’s car when he took her up on the offer to search where he wanted that she indignantly made when he was talking with them earlier.

He arrests her for the murder of Tyler Morgan and we go to commercial break.

When we come back we hear Jessica asking the Sheriff “What do you mean, no bail?”

He explain that mountain folk have long memories and short fuses, not to mention funny ideas about the law, and if he let Molly out on bail he might as well hang out a sign saying “hunting season is open.”

Jessica’s protests are interrupted by Eben storming to get Molly. When the Sheriff tells him that he can see her but he can’t take her home, Eben threatens that he’ll be back and he won’t be alone. (There’s also some talk by Jessica of appealing to higher authorities which Eben disregards.)

The scene shifts to the boarding house where Jessica is talking with Carlton Reid about how the miner’s legal society will help out. They’re interrupted by Bridie arguing with Travis. She demands to know where he was and he says that he was out hunting. She asks, incredulously, “until 3am?” He replies that he’s not a baby anymore and can stay out at night if he wants to, then adds in a highly accusatory tone that she does.

Carlton follows Travis outside and talks with him a bit. It’s done in such a way as to incriminate Travis, which almost certainly means that he’s innocent.

After Carlton leaves Jessica gets Bridie to come help her open a window that always sticks after the rain, then tries to ask her about her having gone out as if it was small-talk. Bridie lies, though, and says that she didn’t go out. After some pressing, she admits that she was Tyler’s mistress because she needed financial help. Though they got closer over time. However, she was worried Travis would find out since he was nearly grown.

I’m not sure what she’s talking about here; Travis looks like he’s twelve and the actor was fourteen at the time of filming, which is not “nearly grown.” He’s still quite a bit shorter than she is. Be that as it may, this was her concern and so she went up the cabin last night to try to end it once and for all.

When she got there, Tyler was dead.

She didn’t call the Sheriff because that would have let the whole town know about her and Tyler. Jessica was surprised that no one knew and she said that Nora (his wife) had an idea a few years ago and she threw such a fit it scared Tyler off of seeing her for a while. She doubts that Nora knew he’d started up again, though. If she did, she’d probably have killed Tyler.

Jessica takes this as her cue to go interview Mrs. Morgan.

Her pretext is asking for Mrs. Morgan’s help in calming down the situation which Reese is stoking. Not much comes of it except for admiring Reese’s skill with a gun, which she takes to be responsible for the shooting ribbons near a bunch of guns over the fireplace and Mrs. Morgan saying that they’re actually hers, not her son’s.

Jessica congratulates her but she demurs. Around here most people can shoot the petals off of a daisy before they’re ten years old. They’re interrupted by a phone call from the funeral parlor and Jessica goes to leave. As she’s almost out the door Nora tells her that she’s sorry that she couldn’t help—Reese is much like his father: it takes a loaded gun to get his attention.

On her way home Carlton drives by and picks her up, saying that there’s trouble—the Sheriff says that he’s got Molly cold. Jessica objects that the loaded gun was obviously planted. Carlton concurs, saying “Hell yes. I mean, anybody could have grabbed that gun out of that unlocked rack by the door and shot Tyler.”

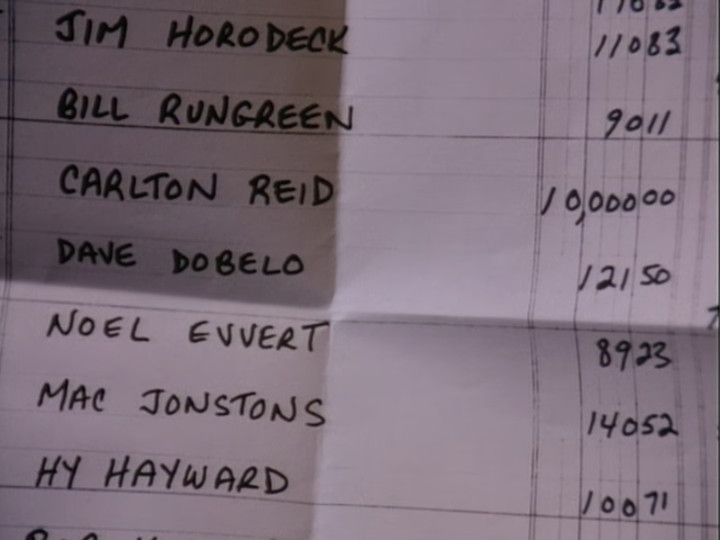

After making this unnecessarily detailed and thus incredibly self-incriminating statement he then explains that that’s not all the Sheriff has, though. Reese went through the cabin and found a ledger sheet had been stolen out of the company’s 1978 payroll. (This is the year that Molly’s father was killed.) The Sheriff thinks this cinches it.

Complicating the matter, Eben has gathered his friends and is planning to storm the jail to take Molly. Jessica suspects that if Reese finds out, there’s likely to be an all-out war.

They arrive at the Sheriff’s office just as Eben and his mob are coming.

Jessica tells Carlton to get the Sheriff while she tries to hold them off. The sound of a gun being cocked announces that Reese and his men have showed up. Both groups file into the area in front of the Sheriff’s office. You can’t see it in this picture but a surprising number of the men on both sides are armed only with sticks or gardening implements, which is a bit odd given that they would all almost certainly own a half-dozen rifles each.

Jessica looks back and forth, worriedly, and we go to commercial break.

When we get back, there’s some yapping on all three sides until the Sheriff comes out, explaining that he’s going to follow his duty in keeping Molly in jail, but without any uninvited help from Reese.

He points out to Eben that Molly’s innocence is for a court to decide, not them, and Molly would be the first to agree. Eben relents, but with the warning that if any harm comes to Molly a court will not be involved in settling the score. He and his men leave. Reese and his men also leave.

Jessica follows the Sheriff inside.

Jessica makes the point that Molly would not have bothered to steal the payroll records when a subpoena would have forced the company to hand it over, and she told Jessica (in front of the Sheriff) that she was planning to subpoena those very records.

The Sheriff very reasonably points out that this doesn’t make sense as an attempt to frame Molly since only Molly, Jessica, and the Sheriff knew that she was planning to subpoena those records. Jessica admits this and says it leads her to the conclusion that somebody stole the record because he or she didn’t want what was on the records found for his own reasons. (Why old payroll records were kept at Tyler’s cabin rather than at the mining company headquarters was not discussed.)

The Sheriff’s phone call that he was trying to make while he was talking to Jessica finally goes through and he manages to talk to someone who he asks help from, explaining that he lost the key to his rifle rack and needs the guy on the other end of the phone to pick the lock. Jessica suddenly realizes what she heard earlier and leaves.

We next see Jessica finishing up a phone call back at the boarding house. Bridie comes in and brings her black coffee. Jessica asks Bridie about the explosion which killed her husband and Molly’s father. Bridie said that she and Tyler spoke about it and he always swore that he wasn’t involved. Jessica points out that this phrasing makes it sound like Bridie doesn’t believe it was an accident either and Bridie says that it was a long time ago and best forgotten about.

Jessica pushes and Bridie tells what happened. Her husband had told her that Joe Connors had found some document that proved that there were fishy doings on at the mine and that he was going to read the document aloud at the union meeting the next night but when he went into the mine in the morning he never came out again. That was that. Molly’s mother took her to kin in Maine. Eben and some friends nearly tore Joe’s place apart looking for the proof but never found anything.

Jessica then says that she may know who killed Tyler Morgan and why, and when she goes to Eben’s house she may find the evidence to prove it. Bridie asks if she oughtn’t to tell the Sheriff her suspicions and Jessica replies, “the moment that I have proof.” This allows the setting up of the complicating factor of Travis eaves-dropping on them. His face looks like he’s planning trouble. Then, after an establishing shot of Eben’s house…

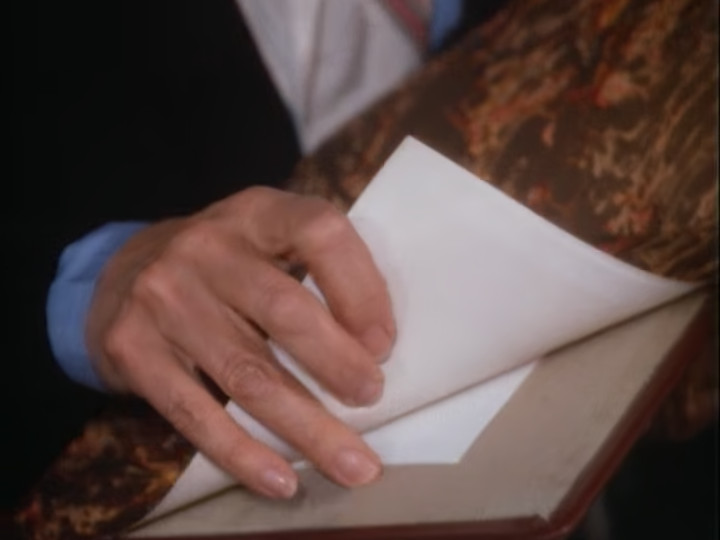

Eben gets cold-cocked while sharpening an ax in his shed. When Jessica comes up to the house, no one answers. So she goes in and checks out the big Shakespeare book which was the one thing of her father’s that Molly had brought to Cabot Cove (meaning that it wasn’t left behind to be searched). Jessica finds a paper carefully hidden in it.

Perhaps he hid it so carefully because he expected someone to come and try to find it while he was in the mine. A bit of a strange precaution to take against his house being searched, but not crazy.

Jessica looks at the document and, her suspicions confirmed, she uses the telephone to call the Sheriff’s office. (She asks the operator to connect her.) While she waits, someone uses an ax to cut the telephone line. And by “someone,” I mean the guy who had earlier provided unnecessary details that incriminated himself in the murder of Tyler Morgan.

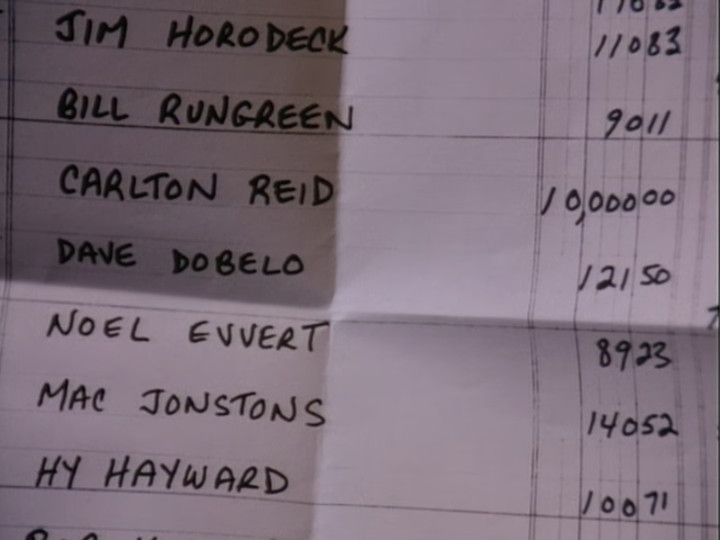

After ensuring that the blade is still sharp, Carlton walks toward the front of the house. As he’s on his way, Jessica notices that the phone line is dead, puts down the phone, and takes a closer look at the payroll and notices some evidence.

A bit weird to put this on the books, but I suppose there was no real downside from the Mine’s perspective. (According to an inflation calculator, $10,000 in 1978 would be worth $49,124.16 in 2023.)

Carlton intercepts Jessica as she walked out the front door. She tries to lie her way out of it but Carlton was looking through the window and saw her find the document in the book. He asks her how she knew he killed Tyler.

She replies that she didn’t know but did suspect because of what he said about the unlocked gun rack next to the door (we even get a flashback). Only someone who had been to the cabin would have known that the gun rack was unlocked and next to the door. Also, Jessica checked up on the union meeting that Carlton was at and while he was there earlier in the evening no one remembered seeing him after the meeting started.

He says that Jessica must think that she’s real smart. Tyler thought he was real smart when he threatened to expose their financial arrangement unless he (Carlton) got Molly off of Tyler’s back.

Jessica asks how far back those financial arrangements went—it must have been a long time. Carlton replies that he never meant to kill Joe. He even offered to cut Joe in on the take, but Joe wouldn’t do it. And as for Danny Harmon (Bridie’s husband), it was just his bad luck that he was working with Joe when it happened. Just like it was her bad luck that she found out the truth with no one around. He pulls out his gun and marches her to his pickup truck. There are places in these hills that only the wolves know about.

As they drive off the front left tire blows out and the car runs through a fence and stops next to a tree that keeps the driver’s side door from opening. Jessica gets out and starts running away. Carlton gets out on the passenger side and starts to follow her but a bullet strikes the ground in front of his feet.

Carlton puts his hands in the air. Travis looks to Mrs. Fletcher to see whether she thinks it would be a good idea to shoot Carlton and Jessica shakes her head in the negative. Travis then relaxes but keeps his gun trained on Carlton, and we fade to Molly and Eben with Jessica at the bus stop.

There’s some minor talk where they ask Jessica the obvious questions and Jessica gives the obvious answer. Then Molly says that the miner’s union has asked her to help with the prosecution against Carlton and if it works out they’re going to put her on retainer to handle all of their litigation. Why, is not said, since she’s done precisely nothing to indicate that she’s a good lawyer.

Jessica gets on the bus and waves, and we go to credits.

I have to say that I’m disappointed that the few remaining moments were spent with Eben and Molly rather than with the Sheriff. I get why they went the way they did, but the Sheriff was the more interesting character.

This was a good episode, overall. It had a complicated mystery with multiple genuine suspects and a least-likely murderer that both legitimately seemed unlikely but also had believable motives for what he did. It also had some decent characters and even a likable and respectable Sheriff.

My biggest complaint is about missed opportunities. Tyler Morgan is a man of tremendous influence within the small town of Colton but half the time is portrayed as if he is the unjust administrator installed by a foreign power who conquered the area. These things are not interchangeable. A man of influence has his influence because he benefits a lot of people in ways that they recognize. A territorial governor can exert influence through power over people he does nothing for, though even that doesn’t tend to last because exerting power costs money while obtaining cooperation tends to be profitable. (For a good example of this, look into why Pontius Pilate was eventually replaced as governor of Judea.)

Tyler Morgan was not the territorial governor of Colton, installed by some foreign power to keep the locals in check. He merely owned the biggest company in town. His having influence would be primarily through the benefits that he gave people and the respect he earned by being beneficial to those people. This is especially true in tight-nit small communities where people had long memories, funny ideas about the law, and most people could shoot the petals off of a daisy by the time that they’re ten. A rich man may be able to get away with bullying people into submission using his money in a city; no one knows each other in a city and everyone is replaceable. In a small town it’s the opposite. A man who wants influence can’t afford to alienate people who have kin nearby that aren’t going anywhere.

The funny thing is that they got this right in the opening scene, where Tyler smiles at all of his workers at the shindig while his fool of a son scowls. He needs the good will of the men there and he knows it. Moreover, he’s clearly well-practiced at being likable to ordinary people, and they generally react well to him. And these are the men who work in his coal mine. How much more must the ordinary people in the community love him, who only benefit from his largess?

All of this is a very missed opportunity in the episode for dramatic tension. Molly’s certainty that Tyler was guilty would be an interesting contrast against the equal certainty of someone who thinks Tyler a saint who would never do something like that. The revelation of Tyler’s affair would hit harder when you think of all the people he let down by it besides just his wife and son. Molly having been wrong that Tyler killed her father would hit harder if there was someone to whom she had to admit that they were right.

That would have been great.

My only other real complaint is mostly just how much we more could have been done had the episode been twice as long, which is not the fault of the writers! They managed to fit a lot into forty seven minutes and they sketched out a bunch of characters who would have been great to learn more about.

There are some nits I am inclined to pick. The biggest among them is that I find it a bit odd that ten-plus year old payroll records were kept in Tyler’s private cabin. It is, frankly, a bit surprising that ten year old payroll records were kept at all. I realize that data retention policies were more primitive back in the 1980s (before a number of high-profile cases of record keeping bit companies in the rear end, as well as some instances of irregular record destruction). And it’s fairly easy to hang onto relatively small records when land (and therefore storage space) is cheap.

Another thing which is not entirely clear to me is why Carlton was “on the take” to such a large degree. As a union rep, the amount that he could do for the company was not trivial, but nor was it enormous. In theory, he could overlook violations of the union contract or of labor laws, but in practice this would probably be substantially limited by his fellow workers having eyes and ears. He could fail to report some fraction of violations, but if he tried to report none of them he would be found out pretty quickly.

The part where Tyler threatened to expose Carlton unless Carlton got Molly off of Tyler’s back was also a bit weird. There has to be something illegal about bribing a union rep to not report labor law violations and even if not, revealing that he’s been doing it for the last ten years would certainly hurt Tyler’s standing within the community. Further, this would rather unnecessarily tie him to the death of Joe Connors in the minds of the town folk since now he would have (to their minds) a motive for it, whereas mine accidents certainly don’t benefit the mining company and decent people need a reason to commit murder. That said, this was only established in a single line and the crime, if anything, makes more sense without this line, so it’s easy to ignore.

Carlton would have gotten nervous with Molly trying to dredge up the ten year old murder that he committed, so his desire to get rid of the old copies of the records makes sense on its own. What makes a little less sense is why there was only one payroll record he needed to destroy. Presumably he would have needed to get rid of all of the records since they’d all contain payments to him. Perhaps he only got paid once a year or something like that; if he was being paid nearly $50k (in today’s money) that might not be a monthly payment. However that goes, it would make sense that at just about his first opportunity he would sneak off to where the records were kept and try to steal them. On finding Tyler there (which he really shouldn’t have been, given the storm) it could easily have made sense to him to kill Tyler in order to get at the records and that, as a bonus, this would allow him to frame Molly which would pretty effectively end her threat of digging up the past.

Those nits picked, I’ve got to say that I really appreciated how the episode had mostly decent characters. Tyler’s son was an awful cardboard cutout, in part the result of the tyrannical aspect of Tyler that the episode occasionally flirted with, but other than that they were all good.

The Sheriff was, of course, my favorite. He had real depth and felt like he had an actual history to him which shaped his character now. He was a decent man doing his best in difficult circumstances, but he was doing a fairly good job. So often the decent Sheriff in this kind of circumstance has basically given up until he finally finds his backbone because of a stirring speech from the hero. Here, he had a backbone from the beginning, and wasn’t pushed around by Jessica any more than he was pushed around by the local figures.

Bridie was one of the better depictions of a prostitute I’ve seen. She had a weakness of character that would make her give into it, but she had other qualities too; she became emotionally attached to Tyler, for example, and she did care about her son. It was a very human touch that she wanted to break off things with Tyler because her son was getting old enough to realize what was going on, but she was several years too late because he understood much better than she knew. People are very prone to think that they’re getting away with things that they aren’t.

Molly was an interesting kind of ingenue. She grew up in Cabot Cove and went on to get a law degree and pass her bar examines in West Virginia but was still very innocent and had an extremely simplistic view of the world. She accepted without question her grandfather’s fairy tale of the wicked mine owner who smited her father with impugnity but who, for some reason, her grandfather never shot as hill justice, despite whole-heartedly endorsing the concept of hill justice. Since she was one of the last characters we saw, it would have been nice if we saw some growth from having learned the truth that her initial understanding was way off.

Travis, the young son of the miner who was killed as collateral damage of murdering Molly’s father, got a nice ending to his story, where he saved Jessica and captured the man who murdered his father. It was a bit of a pity that the actor didn’t look like he was fourteen years old, as the coming-of-age aspect didn’t come across as much because Travis looked like he was still very much a child. Still, it’s a nice touch that he was the one who brought Carlton to justice.

Next week we’re back to New York city for the episode, Wearing of the Green.

You must be logged in to post a comment.