Following my reviews of Whose Body?, Clouds of Witness, and Unnatural Death, I re-read the fourth Lord Peter Wimsey mystery, The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club. This time old General Fentiman is discovered dead in his high backed chair in the smoking room of the gentleman’s club called the Bellona Club. I believe that “Bellona” comes from the Latin root bellum, meaning war, as all the members seem to have been in the army and served in some war or other.

Old General Fentiman’s death would have been remarkable only for life imitating art—there were (apparently) plenty of jokes at the time about someone dying in a gentleman’s club and no one noticing because of the rules against disturbing other members—except for the very curious circumstance that his aged sister had died at about the same time and the terms of her will left her fortune to her brother only if he was alive at the time of her decease; should she have outlived him her fortune was to go to a distant relative to lived with her. The general’s family solicitor happens to be the same Mr. Murbles who is the family solicitor of the Wimseys, and he asks Lord Peter to investigate to see if a definite time of death can be established for the old man.

The mystery takes a few twists and perhaps the same number of turns and introduces a new friend of Lord Peter—the sculptor Marjorie Phelps—who we’ll meet again in Strong Poison. It’s a bit less conventional than the first three Lord Peter mysteries, but I recommend The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club. An exploration of English upper class society in the 1920s is always interesting. Incidentally, the title is partially a reference to this—people keep referring to the old General’s death as “unpleasant” or “the unpleasantness” so often Lord Peter starts remarking on it. It’s a decent mystery, and though not one of Sayers’ best, it’s quite enjoyable.

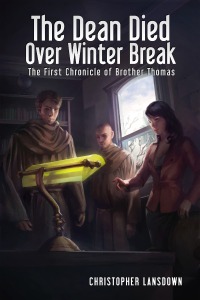

If you like murder mysteries and especially if you like Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey stories, you might like my murder mystery, The Dean Died Over Winter Break.

(If you haven’t read the story and don’t want spoilers, stop reading here.)

(In what follows, I discuss the structure and execution of The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club with the purpose of learning from it because it is a good story. Everything I say should be understood as an attempt to learn from a master mystery writer. Criticism should in no way be taken as disparagement, as I dearly love the Lord Peter stories.)

The first and most curious thing to note about The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club is that it is really two (connected) stories. The first half of the book is the story of trying to figure out when old General Fentiman died. The second half is trying to figure out who murdered him. This is an interesting choice in that the first half of the book feels less important than it really is. It also has the effect of shifting who the important characters are halfway through the book. In the beginning it was Major Fentiman and the mysterious Oliver. Well, the somewhat mysterious Oliver. He’s not really a very plausible character on one’s first read through the book, and I think it’s nearly impossible to suspend one’s disbelief about him on subsequent read-throughs. It doesn’t help that Lord Peter doesn’t believe in Oliver either. On the other hand, this does give the book a twist, and it gives the characters a chance to act in ways they might not have, had murder been suspected from the beginning.

Now, this sort of twist can be done in one of two main ways:

- The solution to the early mystery is provided by solving the murder.

- The solution to the early mystery leads us to the mystery of the murder.

The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club is a variant of #2. Technically the early mystery (when General Fentiman died) is solved shortly before the murder mystery is discovered, but Lord Peter has arranged things so that the exhumation of the body proceeds anyway and the murder is discovered. Upon consideration, this may actually be a third way for this twist to be done:

3. The sleuth investigates the early mystery as a pretext for investigating what he believes is a murder but can’t yet prove is.

Once it is discovered that General Fentiman was poisoned, it is revealed that Lord Peter expected it and wrangled the exhumation of the body specifically to prove it. I do wish that Lord Peter wasn’t quite so subtle about it, though, as the early investigation doesn’t feel connected to the murder investigation, at least on my first two readings. So when Inspector Charles Parker congratulates Wimsey on having handled the case masterfully, it feels a little un-earned.

Which brings up the subject I find very interesting of the good Inspector. This is the second to last book in which he plays a major role, and he only plays that roll in the second half of it. Since the early mystery about when old General Fentiman died was not a police matter, Parker had nothing to do with it. Now, one could chalk this up to the limitations of a police officer as a friend to a sleuth, but this need not be the case at all. Charles Parker was a good friend of Lord Peter; the two could have discussed Lord Peter’s case over cigars and wine at Lord Peter’s apartment. And yet Sayers didn’t do that. And in the very next book we get introduced to Harriet Vane, with whom Lord Peter falls instantly in love. (In fact, I believe he fell in love with her prior to the first page of Strong Poison.) I can’t help but wonder if Sayers tired of Charles Parker, or simply felt he was deficient as a foil for Lord Peter. In any event, he had given her good service and she in turn gave him a good retirement—he would be promoted to Chief Inspector and marry Lady Mary Wimsey.

I think that part of the problem with Charles Parker was that Sayers never really let him become interesting. She gave him a trait which had the potential to be very interesting, but didn’t commit to it. I mean, specifically, that he read theology in his spare time. So far, so good. The problem is that he didn’t seem to learn anything from it. He never talked about it—even when it would be relevant. I don’t think that Sayers would have had any difficulty in writing such a character since she was a religious and well educated woman. Yet still, she didn’t. For whatever reason she seemed most fond, and most comfortable, with writing non-religious or even irreligious characters. At least intelligent ones. She had no real trouble with the middling or unintelligent religious characters. The one exception I can think of being a priest in Unnatural Death. He was very well done, though he only appeared for a page or two.

Of course, the lesson seems to be a rather obvious one: always commit to your characters. Whatever their traits, commit. And if you can’t commit to a character, pick a different character.

Speaking of characters, like Clouds of Witness, there’s an extremely unpleasant character in The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club. Which, I suppose, does at least fit in with the title. I’m speaking, of course, of Captain George Fentiman. I suppose that he was to some degree a commentary on World War I, but I found the constant fighting with his wife—and nearly everyone else—was wearying.

I don’t mean to suggest that such an unpleasant character serves no purpose, however. Captain George was a suspect, and so his aggressiveness and anger do serve to cast suspicion upon him. For that matter, Farmer Grimmethorpe was a minor suspect in Clouds of Witness. But in neither case were they really developed as suspects. Grimethorpe was given a good alibi, and in any event he would have been far more of a suspect had the victim been beaten to death, not shot at close quarters. Simlarly, Captain George would have been far more of a suspect had old General Fentiman been, well, shot at close quarters, not poisoned.

Further, Captain George pretty clearly had no opportunity to murder old General Fentiman. It is hardly plausible that he kept a fatal dose of digitalin on hand should he happen to run into his grandfather on the street in a place he would never have expected to meet him and to then somehow talk the old man into taking it in a place (a taxi cab) where it is most unnatural to eat or drink anything.

I think that when it comes to lessons for writing murder mysteries, if one is going to give a character traits which make them unpleasant to read about, it is best to make them a highly credible suspect. This can also make some tension where the detective would be only too happy for the unpleasant character to be the murderer, which makes them second guess evidence against the character because they are worried about confirmation bias. It can also serve to make the detective more virtuous when he exonerates someone he has come to dislike. At the same time this can become a trap of making a suspect too obvious so that he isn’t suspected; which can make for a good twist where the unpleasant, angry man did actually commit the murder.

(Incidentally, a complication one doesn’t see too often is an accessory after the fact who is the brains of the operation. One sees often enough an angry man who does the brutal work collaborating with an intelligent man who designs the murder for him, but an intelligent accomplice who enters only to clean the murder up is, I think, uncommon.)

When it comes to the murder in The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, I’m not sure what to make of it. It is established very early that the old general went to Dr. Penberthy shortly before he died, and therefore that Dr. Penberthy had basketfuls of opportunity to poison him. And of course as a doctor he had ample access to digitalin. The only thing he lacked was a motive. And the motive he had was comprehensible enough, though it does feel rather a lot like coincidence. Granted, an explanation is given, though it’s one that’s guessed at. Being old General Fentiman’s doctor, he heard about the family quarrel that would result in Lady Dormer’s money going to Ann Dorland, and so he made her acquaintance and seduced her. But this is still a bit far fetched since the old man never spoke of his sister and I don’t see why he’d take the doctor into his confidence on a matter too painful for him to ever speak of. Especially since he blamed his sister and didn’t feel any guilt he needed to try to rid himself of.

Granted, it’s often a good idea for the murderer to be connected to the deceased in a manner that is not generally suspected. Still, Penberthy just never felt like he was enough of a character to me to justify the secret engagement. I think it’s that he never showed up except in his official capacity as a doctor. This puts him in the same class a butlers and other servants; one fails to suspect him not because one is misled by a clever disguise but because one knows nothing about the character at all, and as mysteries go, everyone whom one knows nothing about is interchangeable.

The obvious exception to the above is where one learns about the culprit under a different identity, learning more and more, until one starts to suspect the service characters of being the other identity. I’m talking about plots where long lost cousin Ernesto, who will inherit, took a job as the butler (having shaved his famous mustaches) in order to poison his wealthy relative and intends to inherit from afar and fire the domestic staff so that they won’t recognize him when he takes possession. That sort of thing is tricky, but can be made to work. Agatha Christie did it well in Murder in Mesopotamia. Chesterton also did it well in The Sins of Prince Saradine, though a short story has different rules than a novel does.

This does not apply to Penberthy, though, since he is revealed to have been Ann Dorland’s fiance on the same page that it was revealed that she had a fiance.

I’m also a bit dissatisfied with Ann Dorland’s appearance at Marjorie Phelp’s apartment. When Lord Peter asked Marjorie about Ann, she barely knew the girl. That makes Marjorie a strange confidant to fly to when Ann thinks she’s about to be accused of murder.

On the other hand, Ann Dorland is a pleasingly interesting character. Intelligent but innocent, we meet her in the position of having made many mistakes but is able to learn from them quickly with a bit of guidance. Her likability redeems many of the circumstances surrounding how we meet her and I think ultimately pulls the story together. In that last part it’s especially important to notice that the character, though largely a plot point in the beginning of the story, becomes a real character with real personality in the end. There’s a good lesson in that, which is to make sure to give even minor characters their own personality. It doesn’t have to be a lot, and more importantly it doesn’t even have to be at he beginning. One shouldn’t push that too far, but when the reader learns about a character’s personality, their memory fills it in for them earlier in the book, too. (It is important that the author know who the character is early on, though, so that the character is consistent when he is finally developed.)

And in the book we come once again to the murder committing suicide rather than facing justice. It’s not really the suicide that I dislike so much, but the way that Lord Peter approves of it and worse, helps it happen. Granted, Lord Peter isn’t Christian and so it’s not out of character for him, but I don’t like having my nose rubbed in how he isn’t Christian. I suspect that’s what really gets me about it. It’s one thing to enjoy the virtues which pagans have, but it’s quite another to have to look at their vices.

You must be logged in to post a comment.