On the ninth day of December in the year of our Lord 1984, the seventh episode of Murder, She Wrote aired. It was called We’re Off to Kill the Wizard. (Last week’s episode was Hit, Run, and Homicide.)

There’s a man inside the car who is on a car phone talking to someone named Horatio.

For those who weren’t alive in the 1980s, a car phone was a cell phone actually build into the car. This worked better than hand-held cell phones for several reasons, but the primary one was that it had a better antenna and could be powered by the car’s generator. Cell phones in this era were analog devices, and not very different than talking over a radio only with private channels. They were also extremely expensive and pretty rare. This means that this guy is rich and important.

Anyway, the guy promises Horatio that he will do whatever it takes to bring Mrs. Fletcher back with him.

The scene then shifts to Jessica working on a bicycle while two kids look on.

The boy’s name is Billy. The girl’s name is Cindy. You can just see their mother in the background. She walks up a moment later, after Billy rides off on the repaired bicycle. (Apparently their father couldn’t figure out how to fix it and was ready to junk it. Jessica has one just like it back home in Maine. Given that this is a BMX-style children’s bicycle, I assume that the similarity is that her bicycle also has two wheels.)

Her name is Carol Donovan and she’s Jessica’s niece (her children share her last name). She says that Jessica’s flight to Kansas City has been confirmed, but won’t she consider staying longer?

Jessica replies that she won’t because a good guest is like Haley’s comet: seen and enjoyed seldom and briefly. Right after her lecture, she goes straight home.

This is interrupted by the car pulling up and the guy on the car phone stepping out of it. His name is Michael Gardner and he’s an ardent admirer of Jessica and her work. His employer, whose name is Horatio Baldwin, who goes by the stage name Horrible Horatio, desperately wants to meet her. Little billy is excited at the mention of Horrible Horatio. He runs theme parks throughout the country and today he’s got an opening of a new venture, Horatio’s House of Horrible Horrors (or words to that effect). Little Billy and his sister are so desperate to go that Jessica relents and accepts, despite obviously hating the idea.

It’s apparently medieval themed.

The scene opens with a monk in a cart being led to a gallows. The monk is Horatio Baldwin, and he protests that it’s all a big mistake. He keeps protesting as he’s led onto the gibbet and the noose is fitted round his neck. His cries for help are eventually answered by a robin-hood like figure standing on the wall.

He swings in on that rope and wrestles with the executioner. Unfortunately for Horatio, in their tussle they knock into the lever which operates the trap door, and Horatio falls. The crowd is aghast, but then Horatio appears, laughing, at the top of the castle and assures everyone that he’s fine. The crowd applauds.

Michael Gardner approaches Jessica and her niece and grand-niece and grand-nephew and asks how they enjoyed the show. Jessica says that she found it appalling, I think because she’s morally opposed to fun. Or perhaps it pains her to see children enjoying themselves at something other than a founder’s day picnic. Anyway, Michael says that Horatio is ready to meet her and he’ll arrange for the rest of the family to tour the park.

Horatio meets her in an underground office.

He looked better in the robes, but then most people do. He also has a kind of British accent, which is never explained. He tells her that it was good of her to come and she replies, “How could I not? I had two loaded children pointed at my head.” She says that she doesn’t want to be rude but wants to get away as soon as possible.

When he says that it must seem odd to have an office complex beneath the park, she says, “perhaps you have an aversion to sunshine.”

Jessica isn’t usually this rude and I don’t know why she’s so desperate to get away from her niece, Horatio, and the entire city. It’s an odd choice for the writers because it’s just unpleasant without adding anything. I think this may be because of the idea many screenwriters had that there must be “conflict” which they took to mean everyone hating each other, rather than somebody having some goal that they can’t easily achieve.

Horatio is then accosted by Nils Highlander.

He doesn’t care that Baldwin is busy; he’s been busy for weeks but won’t be so busy if the city shuts him down for safety violations. This upsets Nils because it’s his name on the building permits and his reputation that’s at stake. I’m pretty sure that’s not how it works unless Nils is in charge of the safety situation and directly responsible for it, making the safety violations his fault. I suppose that they’re trying to set it up that Horatio personally intervened and forced the people who report to Nils to introduce safety violations in the rides in spite of what their boss was telling them. You know, like highly successful businessmen do. Because that benefits them somehow. They enjoy micromanaging operations in order to create fodder for lawsuits.

Horatio yells at Nils and he leaves. Horatio then directs Jessica to his office and she pauses and asks if he’s lured her here in order to offer her some kind of job. Why she thinks this I can’t image unless it’s because she’s read the script. Anyway, Horatio responds, “Mrs. Fletcher. Please allow me the seduction before you cry rape.” Jessica smiles at this and they walk off to his office.

Somebody sticks his head out of the door this was said next to.

The name on the door is “Arnold Megrim” so perhaps that’s this character’s name. I’m sure we’re going to see more of him later.

The way to Horatio’s office is through an antechamber with Horatio’s secretary.

Her name is Laurie Bascomb. Horatio instructs her to see that they’re not interrupted, though before they go into Horatio’s office she mentions that he had an important call from “Mr. Carlson”.

He replies, “I’ll be the judge of which calls are important, Miss Bascomb.”

The dialog isn’t realistic, of course; the goal is to paint the characters as efficiently as possible, not to scenes in which it’s possible to suspend disbelief. That’s a pity because it’s possible to do both and many Murder, She Wrote episodes do, but at least we’ve learned that Horatio is the scum of the earth.

Before they go in, Jessica spots one of her books on Laurie’s desk and offers to sign it for her. Laurie says she’d be honored if Jessica did and mentions that she’s trying to write a book herself. Horatio is impatient at this, of course, because his success up til now has been achieved by alienating everyone he wants something from. Or because we’re supposed to hate him. One of those two. Probably the first one.

The scene then shifts to a different office where we meet another character.

His name is Phil Carlson. Arnold (the guy who stuck his head into the hallway before) comes in and says that J.B. Fletcher actually came, but Phil is unimpressed. Arnold turns out to be worried, not impressed. This means another park, more red ink, and more falsified accounts. Phil tells him that if he doesn’t like the job, he should quit. Arnold says that he can’t quit, anymore than Phil can. Phil says that he doesn’t want to quit, though, since he’s going to be made a vice president tomorrow. Arnold replies that he was promised a vice presidency two years ago, before Horatio snatched it away.

This is definitely how businesses work, especially successful businesses.

To be fair, people do sometimes cheat and do illegal things, and murder mysteries will, by their nature, tend to focus on those cases because it provides more suspects (as the above was meant to do) and more intrigue. That said, the hurried pace and frank discussions where people are entirely open about doing illegal things feels cartoonish.

Anyway, as Arnold leaves he says, “he’ll do the same to you, Phil, just watch.” Given that Phil will find this out tomorrow, this seems unnecessary. Phil will certainly find out soon enough, one way or another. Phil considers this after Arnold leaves, though, and then we go back to Jessica in Horatio’s office.

Horatio’s idea is “Horatio Baldwin Presents: J.B. Fletcher’s Mansion of Murder and Mayhem.” He promises her a panoply of blood and gore, chills and thrills. The kids will love it!

Obviously, Jessica hates this because she’s a schoolmarm scold whenever it comes to physical violence, but I find this weird because it’s a complete misunderstanding of the murder mystery genre. Jessica may be a literary titan who’s work is known to three quarters of humanity and is to (almost) everyone’s taste, but the among the one quarter who doesn’t know her work is the majority of people who want to go to haunted houses for fake gore and jump scares. It just makes no sense at all to try to base a haunted house theme park on a mystery writer’s books. Horatio should be even more against this idea than Jessica is, since he has better reason.

There’s an interesting bit of conversation in which Horatio says that violence is money in the bank and Jessica is appalled. He asks her where she gets her moral outrage from. He’s read her books and they’re in the same business. She replies that she writes her books for people who read, while he stages his bloodbaths for tots who have not yet learned to differentiate his sordid charades from the real world.

This is idiotic, of course, but I’ve finally remembered that back in the 1980s there was a kind of woman (whom Jessica is meant to portray) that was deeply upset by portrayals of violence in the media, thinking that it would destroy civilization and debase everyone into barbarians. Tipper Gore comes to mind as one of the champions of this line of thinking. They were wrong, especially in their expectation that graphic violence would become pervasive. Graphic violence is not interesting to most people; even to the people who find it interesting it doesn’t tap into any strong instincts in the way that explicitly sexual content does. And that’s where I have a real antipathy to the people who were only against graphic violence. A particularly stupid catchphrase for this kind of idiocy was, “I’d rather a child watch two people making love than two people trying to kill each other.” Jessica never said it, but she might have; this is one of those aspects of Jessica’s character which I didn’t notice when I was a child but notice all too well now—Jessica wasn’t a good woman. She was a shrewish scold with no real principles except for a strong dislike of unpleasantness. It’s a real pity, but on the plus side it only ruins the occasional episode.

Anyway, this speech by Jessica is idiotic, in particular, because children so young they can’t tell that fake blood is fake don’t buy tickets to parks. In fact, Horatio’s parks almost guaranteedly have a minimum age for admission without a parent for simple practical reasons. He’s running amusement parks, not daycares.

This stupid exchange goes on for a bit longer, giving us an excuse to find out that Horatio has a button on his desk that locks his door. He had it installed to keep people out but uses it to lock Jessica in when she tries to storm off, but relents when she threatens legal action. This is obviously only here in order to establish its existence for later. I really wish that the writer for this episode, Peter S. Fisher, had tried on this one. He wrote Lovers and Other Killers and (aside from the scene with Jessica, the baby, and the nuns) it was much better written.

After he unlocks the door Jessica leaves and Horatio calls someone by the name of “Mickey” on the phone, telling him that they’re going to need his special brand of research in order to convince Jessica to agree to the mystery-novel-blood-and-gore theme park. This is so dumb I had trouble typing it.

Fortunately things pick up in the next scene, which is that night. A security guard at the park hears a gunshot and runs off to investigate. He’s joined by another security guard and they go into the anteroom to Horatio’s office. They wonder what Horatio is doing there this late at night and where Laurie Bascomb is because she never leaves until he does.

They check the door and Horatio has it bolted from the inside. They knock, but no one answers. The security guards wonder what to do and one recalls that (Phil) Carlson is still here and so they give him a call on the phone in Laurie’s office. Why they’re consulting the architect, I don’t know, but he directs them to break down the door, using the fire ax if necessary, and he’s on his way.

The guard does as he is bid and breaks down the door with the fire ax, then enters through it.

They don’t enter very far, though, when they see Horatio.

The camera zooms in so we can see the gun in his hand. The guards then walk up and take a look.

The one asks the other if he’s dead, and the other simply replies, “I don’t know.”

As they start to lean in to take a pulse, Phil calls to them from the door.

Phil walks in, looks at Horatio, then we fade to black and go to commercial.

When we come back from commercial break, little Billy is talking to his father about how great a day he had at Horrible Horatio’s Medieval House of Horrible Horrors. He’s telling his father about how everyone thought that the guy really got hung when Jessica interrupts to correct Billy that the correct word is “hanged.” Drapes are hung, people are hanged.

(The father’s name is Bert, btw.) This important lesson over, the phone rings and it’s for Bert. Apparently he’s been assigned to the investigation of Horrible Horatio’s Suspicious Suicide. Also, the Captain wants to talk to Jessica. Jessica expresses her conviction that it’s not a suicide since Horatio was not the kind of man to kill himself, and they’re off.

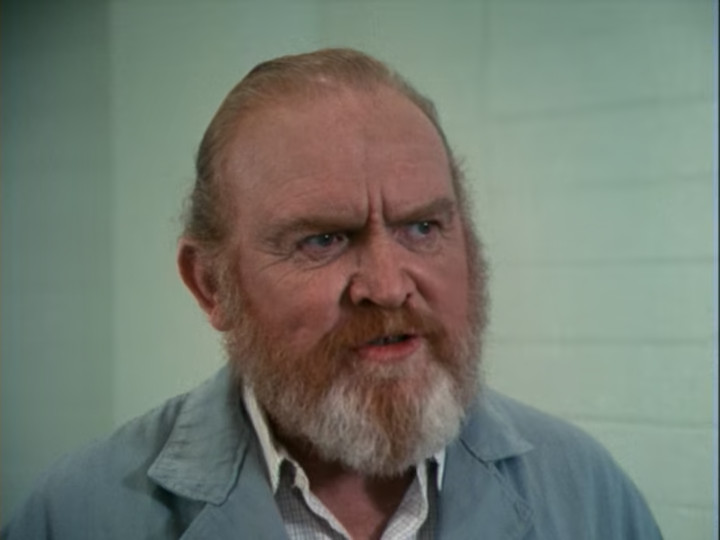

When we get to the scene of the crime we meet the Captain.

Played by delightful character actor John Shuck, the character’s full name is Captain Davis (he never gets a first name).

Anyway, while the physical evidence rules out murder, Horrible Horatio took a blow to the back of the head which was the cause of death, not the gunshot. So we’ve got ourselves a locked room mystery!

The Captain wants Jessica’s opinion on it because she creates such ingenious plots in her books. She has a way of creating “impossible” murders that are not really impossible. So he’s hoping that creativity will help here.

I don’t know why, but Jessica always responds negatively to this kind of request for help. Approximately as negatively as she does to police detectives who don’t want her to stick her nose in when she offers help unasked. I don’t know why the writers thought that this was a good idea, because it was a bad idea.

In this case Jessica isn’t as bad as she was in Hooray for Homicide; all she says is, “I’m sorry to disappoint you but I don’t have a clue.” No offers of help or anything, or even an expression of interest.

The next morning as Jessica comes back from her morning run in a full body sweat suit she finds the newspaper at the door and looks at it.

(The full headline is “Mystery Surrounds Baldwin Death.” I can’t really make out the text of the article but from the words I can make out it’s clearly got nothing to do with the episode. Presumably this was just stuff pasted over a real newspaper. Also, it’s curious that they used the actress’s head shot rather than taking a picture of her with the haircut she had in this episode.)

As an amusing bit of scenery inspection, here’s the front of the house as Jessica runs up to it:

Now, here’s what we can see out the door when Jessica walks in:

Let’s do that computer-enhance stuff of what’s over Jessica’s shoulder:

Not as good as in the movies, but it will do. We can clearly see that the interior, if it’s not just a sound stage, is very much not of the building that the exterior was of. If this is a sound stage, I’m impressed with how much they were able to make it look like there’s a real outdoors outside that door.

Anyway, when Jessica comes in, she immediately picks up the phone and calls the airport reschedule her airplane flight to a later one and then get a flight returning in the evening.

We then cut to the inside of one of Horrible Horatio’s rides.

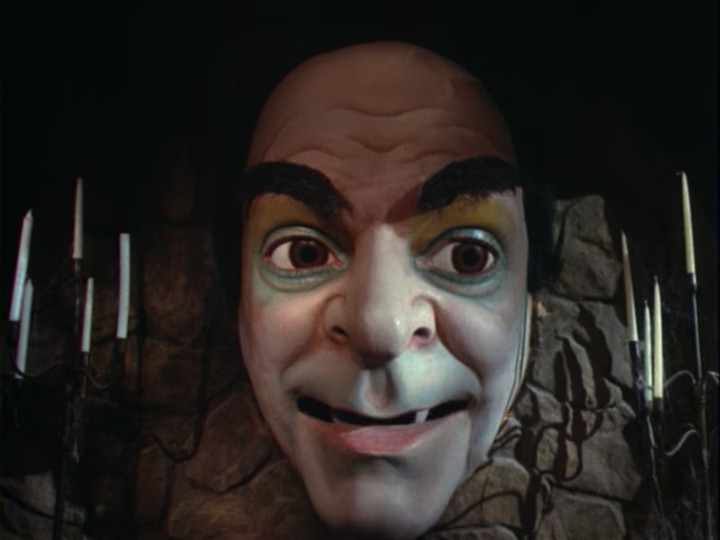

The lips move a bit as a recording of Horrible Horatio’s voice plays, telling guests that they’ll have some moments of panic but they were warned. I’m not sure whether it’s Horrible Horatio’s face and voice because he was that much of a megalomaniac/celebrity or because it saves money on casting. Maybe a bit of both.

After a few lines, it begins to slow down and eventually stops. Phil and Nils come up to it and Nils says that it’s not the relays, he’s already checked that on another machine. They open it and begin to look into its guts when Jessica walks up looking for Phil.

Jessica asks Nils if he got his problem from yesterday solved and he sourly replies that he’s got no problems, he just does his job the best he can. A phone rings and he excuses himself, explaining that he programmed his phone to forward his calls here.

Jessica talks with Phil a bit and they discuss how literally everyone who’d ever met Horatio is a suspect, at least as far as motive goes. Phil concludes by saying that, personally, he thinks that Horatio did the world a big favor, but if not, let him know who to thank. He then excuses himself as having work to do.

Jessica then goes to the airport, where Michael Gardner intercepts Jessica. He’s armed and shows her his gun by way of persuading her to come with him. Jessica does, though she protests it’s not because of the gun but because her curiosity was piqued. This is weird because she says it insincerely, but it’s completely implausible that Gardner would actually shoot Jessica in front of dozens of witnesses, so it kind of has to be true.

They board a private airplane, where Jessica meets Horatio’s widow, Erica Baldwin.

There’s some small talk in which Jessica mentions that Erica has buried four husbands so far, according to her nephew, Bert. It also comes up that she used to be a showgirl. There’s also a bit where she asks if it would surprise Jessica if she said that she loved Horatio very much, and when Jessica assures her that it would, she replies, “then I won’t say it.”

Jessica asks about Michael’s attachment to her and she explains, “for the past two years, Horatio chose a celibate life. With Michael’s cooperation, I didn’t.”

Technically “celibate” means unmarried. What she actually meant was “continent” or “abstinent.” For some reason Jessica doesn’t correct her on this point of English.

Anyway, the conversation turns to the police suspecting murder and Jessica says that she’s concerned for Laurie Bascomb, and they’re very mistaken if they think that they can get her to stop investigating. On the contrary, though, Erica so much doesn’t want her to stop that she’s prepared to offer Jessica $100k ($297,766.38 in 2024 dollars) if she can prove that Horatio didn’t commit suicide. Eleven months ago he took out a life insurance policy worth two million dollars. This won’t pay if it’s suicide. He hardly seems the kind to have paid money which would only benefit other people, but life insurance policies are necessary to murder mysteries, so it’s fine.

Oh, and when Jessica says that she neither needs nor wants Erica’s money, Erica replies, “then give it to the starving orphans. They do.”

As everyone buckles up for takeoff, Jessica says that she doesn’t have the faintest idea how she can prove Horatio didn’t kill himself.

In the next scene Jessica returns to her Niece’s house via a taxi. After some apologies about them being worried and Jessica saying she tried to call the house which explains nothing that we saw, it turns out that they have company—Laurie Bascomb. She comes up to Jessica and says that she wanted to call her and doesn’t know what to do. Jessica tells her that it’s alright, but Laurie says that it’s not alright. “Horatio Baldwin is dead and I killed him.”

And on that bombshell we fade to black and go to commercial break.

When we get back, Jessica is pouring coffee for Laurie as we clear up that it’s not actually true that she killed Horatio Baldwin, she just feels responsible because she left her desk early. This absurd justification for the cliffhanger before commercial break feebly explained, we then get a flashback as to what happened.

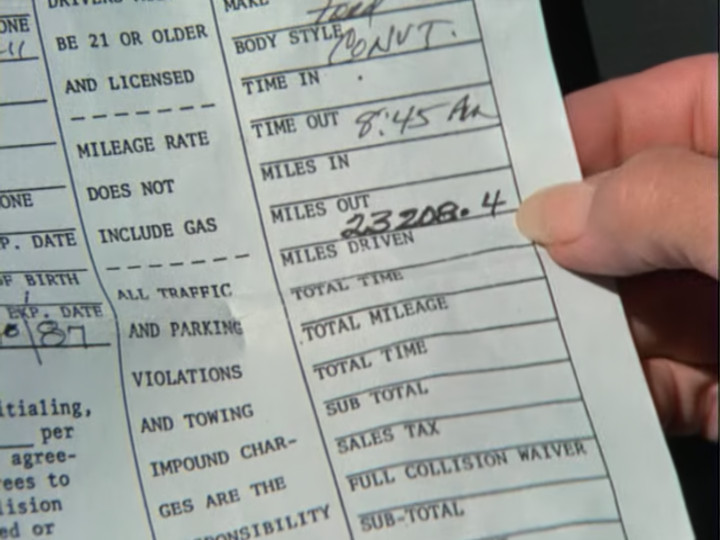

Laurie wanted to quit because she couldn’t stand how Horatio used people, but he threatened her. He would reveal certain things about her past if she quit. She followed him into his office, then ran out back into hers and he followed her. He told her that she’d never work again but she didn’t care, she just wanted to get away. He laughed at her and went back into his office, shutting the door behind him. She heard the bolt slam into place at a quarter to seven.

Bert picks up on the blackmail and Jessica points out that if he was blackmailing her, he might have been blackmailing others. Laurie says that he had files on Phil, Arnold, Nils—all his key people. Laurie didn’t know where they were kept, though.

Jessica suggests in his office, given all of his security precautions. This is ridiculous, of course, since he has theme parks and consequently offices throughout the country—this one is only his latest—and that doesn’t even matter because the best place to keep something like incriminating evidence you probably won’t have to use would be in a safe deposit box in a bank, not in the office of your latest theme park. That’s not very convenient for a TV episode, though, so he will have kept it here as a character quirk.

Bert and Jessica go to Horatio’s office to search for a secret compartment for the blackmail files. Captain Davis comes in and asks why Bert didn’t arrest Laurie Bascomb. Before Bert can answer, Phil comes in and asks what’s going on.

The blocking of this is kind of interesting. I’m not sure why they’d arrange these people like this, especially with Phil coming between Bert and the Captain. It feels like it suggests something, but I’m not sure what.

Anyway, Bert answers and says that they’re searching for a hiding place. Phil says that no one could have hidden in here, but Bert says that they’re searching for files. The Captain asks what files and Bert explains about the blackmail. While this is going on, Jessica examines Horatio’s desk and finds the hiding place.

Well, not quite, but she’s on the trail. She wonders why Horatio has a builtin thermostat on his desk. She then notices that it is covered in soot. Jessica then strikes a match on the strange match-holder on Horatio’s desk right next to the thermometer…

…and holds it up next to the thermostat. When the thermostat reads hot enough, his desk slides open, revealing an empty compartment. Horatio was an inveterate gadgeteer, so this is in character! Also, the compartment is empty and the files are gone!

Phil is deeply skeptical of the murder theory, then excuses himself. No one asked him to be there so there was no need to excuse himself, of course.

When he’s gone, Jessica remarks, “for a man whose career has been steeped in illusion, Mr. Carlson has a very closed mind.” Jessica then suggests that they should find whoever did the research for Horatio, since Horatio was unlikely to do his own dirty work.

The scene then shifts to the airport where Arnold Migram is trying to board a flight to Mexico City. There is apparently a sting operation to catch him, for some reason, as the woman at the desk presses a special button to signal the guards that Arnold is there. The guards then apprehend Arnold, though not without a minor chase. As part of that chase, Arnold trips and his briefcase falls, opens, and an enormous number of bills pop out and start blowing in the wind. Some onlookers come to help, but Arnold rushes to it and starts scooping up bills, saying, “This is my money!” over and over again.

Back at police headquarters he swears at the money is his because Horatio owed it to him for ten years of servitude. In the briefcase there’s also the blackmail documentation of him embezzling money, though he says he never took it, it was his associate, Wanda Perlstein. Also, he has no idea how the blackmail documentation got there.

Jessica asks why he ran. He ran because he received a phone call saying that the police had Horatio’s files on him and would be around to pick him up. Bert notes that it was also a phone call that alerted airport security to pick Arnold up. He says this as if it being a phone call suggests it’s the same person, since normally you’d expect the airport to be told by a registered letter or by someone having rented an airplane that does skywriting. This, at least, explains the sting operation to get Migram, at least if we’re willing to believe that airports in the 1980s arrested people on the say-so of anonymous phone calls.

Migram asks if he can go because he’s worried about his cat, and Bert says that’s fine but he shouldn’t go anywhere they can’t find him. You know, like he just tried to do. But Migram says that he can’t anymore because they have all of his money.

After Migram leaves, Jessica looks through the blackmail documentation and wonders if it’s accurate. For example, the dirt on Phil is that he fled to Canada during the Vietnam Crisis, which is hardly a devastating revelation. Also, there’s one person who’s conspicuously absent—Michael Gardner, the business manager.

That night Michael Gardner, wearing a bright red robe over his pajamas, in hotel room on a high floor, hears a cat mewing from his balcony and goes to investigate. When he finds that it’s a tape recorder a figure dressed in black grabs him from behind and throws him off the balcony.

The figure then retrieves the tape recorder and leaves. We fade to black and go to commercial.

The next day Bert talks it over with Carol. As a curious bit of character development, they begin their conversation with him saying that she’s sexy in the morning and her saying that he’s finally noticed. She asks whether Michael Gardner really killed himself and Bert says that there’s no way to know. Interestingly (to Bert), his real name was Mickey Baumgardner, and he was a former private investigator who worked for Horatio digging up dirt. (I’d always thought that “Mickey” was a nickname for Michael, making this not much of an alias.) Also, he was apparently trying to dig up dirt on Jessica, which amuses Carol to no end. Bert asks where Jessica is and Carol says she went over to the house of horrors.

He wants to talk to Jessica so he’s sorry to miss her. There’s a private line into the office so he calls it. It actually goes to Laurie’s desk, and the security guard who had stopped in picks it up and transfers the line in to Horatio’s office where Jessica is.

After Jessica is done with the call she’s about to leave but then gets an idea and picks up the phone, takes off the back cover, and looks at it.

One of the red wires has been cut. Jessica then gets an idea. Talking with the security guard, she establishes that there are two lines, 1998 and 1999, and if 1998 is busy, the call is automatically kicked over to 1999. Like if you use 1998 to call 1999. She demonstrates, and on Laurie’s phone 1998 doesn’t light up and in Horatio’s office the phone doesn’t ring for 1999.

Ned (the security guard) asks what this is all about and Jessica says that she just figured out who killed Horatio and how it was done.

Ned then goes and visits Phil, giving him a note saying that Mrs. Fletcher stopped by and wants him to call her at her Niece’s house. He obligingly does so. She tells him that Michael Gardner had some microfilm that he had hidden. Her nephew thinks she’s bonkers but she knows exactly where it is and so does he—in the attraction that’s not quite working right. She asks if they can meet in forty minutes with the blueprints? It will take that long to get across town. Phil says sure.

This is silly, but since it’s clearly just a setup, it’s fine.

Phil then immediately goes to the ghoulish head of Horatio and turns it on for atmosphere, because when you’re trying to find hidden microfilm you want all of the circuits to be live. Anyway, he finds something he takes to be microfilm and as he does, Jessica, off to the side, says, “How wonderful, Mr. Carlson. You’ve found our prize.”

Jessica then explains that Phil killed Horatio because Horatio didn’t make him a vice president and also had some sort of really bad dirt on him which he replaced before planting the blackmail files in Arnold Migram’s briefcase. He used call forwarding to make it seem like Horatio was killed in a locked room, as Jessica had to seem forty minutes away. That and some misdirection.

Phil says that she’s clever and pulls out a gun. Jessica tells him that he can’t expect to get away with murder and he replies, “But I already have.”

He then shoots and a sheet of glass shatters. It turns out that it was just a mirror and Jessica was safely out of harm’s way. Bert, after cocking his pistol, tells Carlson to freeze and drop the gun. There’s an entire crowd who was watching, apparently, including armed backup.

Phil complies.

Jessica walks up and, after thanking Nils because the illusion was perfect, Phil says that she got lucky that he didn’t know about the microfilm. Jessica takes it from him and says, “Oh, this? No, this is just a roll of negatives from my trip last year to Spain.”

Back in Horatio’s office, Bert explains Jessica’s theory (he gives her credit).

After Laurie left, Phil came to Horatio’s office and Horatio and he quarreled because Horatio reneged on the promotion. Somehow Horatio was struck on the head, possibly when he fell. Carlson thought quickly. He got the gun he kept in his own office, then forwarded his phone to Horatio’s office. He disconnected the light under the line in Laurie’s office. He went into the office and bolted the door. He also disconnected the bell on Horatio’s phone. He then put the gun in Horatio’s hand and shot him in the head.

When the security guards called Phil, the call was forwarded to Horatio’s office where Phil took it. He then moved to the shadows next to the bolted door (there’s a cabinet there which is quite concealing) and pulled the black turtleneck sweater he had been wearing up over his head. There isn’t a great picture of this area of the room; the best one I can find is actually from a flashback when Laurie is telling the story of her fight with Horatio when she quit:

The cabinet is big enough and that corner of the room dark enough to make concealment plausible. When the guards broke in they were focused on Horatio. After they walked up to the desk and while their attention was on Horatio he quietly left the room behind them. In the corridor he got rid of his sweater (for some reason) and rushed back towards the office, calling as he did so.

Jessica remarks that it might have worked, had it not been for their medical examiner.

Later at the airport Bert and Laurie are dropping off Jessica. (Apparently, Jessica forbade Bert from bringing Carol and the kids to say goodbye to Jessica because she hates public goodbyes.)

Laurie tries to thank her and Jessica says that the best way to do that is to start writing that book she’s wanted to write. Laurie says that unfortunately she needs to find a job, and Jessica gives her the check that Erica Baldwin gave her for proving her husband’s death wasn’t suicide. Jessica has already endorsed it over to Laurie.

Jessica then tells Bert, “see you next year” and walks off to her flight.

There’s then a very weird scene where Laurie opens the check as Jessica leaves and is overwhelmed. She hugs Bert for some reason, and mouths “thank you” to Jessica, who is a bit far away to shout to. Jessica smiles and waves back, and we go to credits.

The mystery in this episode was pretty neat. Locked room mysteries only ever have so many solutions, of course—either the room wasn’t really locked, the victim wasn’t dead until after people broke in, or the murderer hid out and left after people broke in. Each of these has variants, though, and it’s in these variations that people can be clever, which this episode was.

It did play a little unfairly with us by not really showing the part of the room that could hide the murderer until late in the episode, but it did show us the guards being focused on the body in a way that might have let someone slip out behind them, so I wouldn’t go so far as to say that it cheated.

In terms of locked-room solutions, I would say that this one is decent, though not brilliant. They do a fairly good job of piling on the evidence that Horatio was alone, or at least that Phil wasn’t in the room. In general they don’t stretch plausibility too much to do it. Phil’s hiding place was pretty concealing and if he chose his time well, he probably could have snuck out behind the guards. He was taking a big risk that they both came in but he didn’t have many options since he had never intended to kill Horatio. Probably the biggest risk was in firing the shot with no clear indication of where it came from. In an underground complex with neither of the guards nearby they’d have no way of knowing which office it came from and with Phil being the only person known to be working late one would expect them to check on him first. Him not being in his office would certainly be a problem. (And you can’t solve this by having the guards nearby since then you’d have expected them to hear Horatio and Phil fighting.) That said, since this wasn’t planned it works for him to take his best chance and the only reason that there’s a mystery is because it happened to work out. It’s fine for the murderer to be audacious and lucky… at first.

It’s also interesting that we’re seven episodes into Murder, She Wrote and have met two nieces and a (female, niece-aged) cousin of Jessica’s. (I didn’t start with the pilot, but that has Jessica’s favorite nephew, Grady, so we can bring the relatives up to four at the expense of considering this the eighth episode.) Throughout the twelve seasons of the show we would only get about twenty relatives of Jessica’s, which is an average of 1.67 relatives per season. We’re currently averaging just under one relative per two episodes. I think that this may have contributed to the perception that Jessica had hundreds of nephews and nieces, since with (around) 260 episodes, the current rate would give us almost 110 relatives. Obviously, the rate of new relatives will go down pretty quickly.

There are a few odd choices in this episode, such as having Horatio’s widow offer Jessica one hundred large to do what she was going to do anyway. It didn’t make her a suspect and I don’t know that else it was supposed to add to the story otherwise.

There’s also the ridiculous business stuff. I really don’t know what to make of it; it’s so absurd that it’s tempting to think it was meant as comedy, except that the serious part of the plot depends on it. A businessman who runs his business by hiring key people at reduced salaries because he’s blackmailing them is not, strictly speaking, impossible. But how much money could he save this way? If he pays his top people $50k instead of $100k, this isn’t much of a savings when you take into account the fifty people making $10k each for each person at the top. Amusement parks are labor-intensive, especially when you include maintenance, security guards, etc. And what sort of quality of employee will you get if you only hire people who’ve done blackmail-worthy things in their life? It would be one thing if Horatio took over a business he didn’t know how to run and was basically managing its decline, but that’s not what’s portrayed. Horrible Horatio is a celebrity who built an empire. Again, anyone can do any evil, but this is just not in character. Someone making money hand-over-fist on his way up would very believably over-extend himself then be desperate to try to cover things, but that’s not what was depicted. Horatio, as we saw him, was still on his way up.

Also, if Horrible Horatio was in financial trouble to the point of cutting corners on safety for his slow-moving flat rides past barely-moving animatronics, why did he go to the expense of building an underground office complex? Excavating enough ground to fit a dozen large offices and then putting a roof on top of it which can hold an uncovered dirt floor (that gets really heavy in the rain) and multi-story buildings would cost a fortune.

And getting back to the issue of character consistency, Horatio was simultaneously charming and went out of his way to pointlessly antagonize people. It is generally good advice to “never make enemies for free” and Horatio gave out being his enemy like he was Santa Claus, if you’ll pardon me mixing my metaphors. It was helpful in establishing suspects, but it felt very much at odds with the charming bits.

This episode was a bit rushed and a bit silly, but at least it was not wacky, so I think that we’re starting to see Murder, She Wrote settle in to what it would be for the main part of its run. It was common for TV shows to need a half dozen episodes or so to find its footing, so we’re not doing too bad.

Next week we’re in both Boston and Cabot Cove for Death Takes a Curtain Call.

You must be logged in to post a comment.