Or you can watch it on YouTube:

Or here’s the script. Bear in mind that was written to be read aloud by me. It wasn’t written to be read by a general audience, though it should be generally readable.

Having looked at each of the Four Horsemen individually—Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, and Daniel Dennett—I wanted to turn my attention to them as a group. There are a number of interesting questions to ask about this group, and since it is basically defunct, but we’re still close to it historically, the answers don’t seem that hard to come by.

The first question I had was: how did these four men come to be called The Four Horsemen. I’ve heard it said that many second-string atheists aspired to be numbered among the Four Horsemen—P. Z. Myers, Lawrence Krauss, Jerry Coyne, Richard Carrier, and others—which suggests the question: what was the original selection criteria? Dawkins and Hitchens are obvious enough, and Sam Harris isn’t too hard to see, but Daniel Dennett is something of a mystery. He doesn’t really seem to be the same league as the rest—whether you’re talking about charisma or popularity. So I did a little digging, and the answer surprised me, though it shouldn’t have.

In 2006, after the success of The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins founded The Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science. Interestingly, The God Delusion was published on the second day of October in that year, so he didn’t wait long to consider it enough of a success. In late September of 2007, the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science—I love how pretentious that name is—convened a meeting of Dawkins, Hitchens, Harris, and Dennet which was recorded and released on a DVD titled, “Discussions with Richard Dawkins, Episode 1: The Four Horsemen”. So, in effect, they gave that title to themselves, which I find very fitting.

Though, in strict accuracy, it is possible that it was the producer of the DVD who came up with the title. His name is Josh Timonen. He was, incidentally, also the director, editor, and cinematographer of the DVD. According to IMDB his other credits are performer/writer for the soundtracks of Hallowed Ground and Safe Harbor, and he did visual effects—specifically the main title designs—for Carjacked, Never Cry Werewolf, and Hallowed Ground. Also interesting is that there is no episode 2 of “Discussions with Richard Dawkins,” though apparently Timonen did film a public discussion with Dawkins and Lawrence Krauss in 2009. I’m guessing that it’s not on Timonen’s IMDB credits because the DVD does not appear to have been published; the recording is available in twelve parts on the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science website, which still says that it will soon be released on DVD along with other discussions with Richard Dawkins. Also, the video continually loads without ever playing. Well, once again we see that only God accomplishes all things according to the intentions of his will; the rest of us only grope around in the dark largely doing what we don’t mean to do and not doing what we do mean to do.

So, our two possibilities for the origin of the name is that the group gave it to themselves or that a marketer employed by Richard Dawkins came up with the name to sell DVDs. Both possibilities are extremely fitting for a group of New Atheists; atheists rarely do anything glorious because, after all, what is glory? Money, everyone over the age of fifteen knows, is far more directly measurable. And indeed, the new atheists stand for nothing if they don’t stand for only believing in the directly measurable.

Also somewhat ironically, according to Wikipedia, which cites a 2012 video presented by the Australian Atheist Alliance—sorry, the Atheist Foundation of Australia—with Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennet, Sam Harris, and Ayan Hirsi Ali, Ali was invited to the 2007 conversation with Dawkins but had to cancel at the last moment. Had she been able to make it, it’s likely we’d never have had the four horsemen at all, both because “horsepersons” doesn’t scan well and because “the five horsepersons” wouldn’t really be a recognizable reference. They’d have had to have been called, “half the plagues” or something like that.

This doesn’t fully explain the four horsemen, though. Why were these particular people invited rather than others? I don’t mean in the proximal sense of exactly what were the precise criteria used in the decision, but rather why were the conditions such that the decision was made the way it was? Dawkins of course was obvious, since it was his foundation which convened the discussion, but the other three raise questions.

The most obvious answer seems to be book sales. The Four Horsemen conversation took place on the thirtieth day of September in the year of our Lord’s incarnation 2007; Christopher Hitchens’s book God is Not Great was published in May of 2007. Dennet’s book Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon was published in February of 2006. Sam Harris had two best sellers, The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason in 2004 and Letters to a Christian Nation in 2006. Ayan Hirsi Ali’s autobiography, Infidel, was also published in 2006. The other aspirants to horsemanship I mentioned before didn’t publish anything relevant until after the fateful conversation which crowned the four men it did.

But this only pushes the question back a little; there have been atheists writing books about atheism for over a hundred years. Why did these men become popular in the time period they did? A few pages of The God Delusion are sufficient to prove it wasn’t for the quality of their thinking or writing.

One interesting answer is giving by The Distributist in his video on why he isn’t a New Atheist any more:

[CLIP<8:23-8:43>: And you see here how the new atheist narrative really rescued the optimism and the idea of the end of history that was popular in the 90s from a lot of events that I think should have caused a much deeper cultural consideration of that optimism.]

He develops his point in some depth and I recommend watching his video in full; this clip doesn’t do it justice. But as much as he makes a very good case, I take a somewhat different view, though I think a compatible one.

As I mentioned, atheism has been on the rise in the west for a long time; in the early 1900s G.K. Chesterton talked about the absurd pretence that then-modern England was still Christian. Both Freudianism and Marxism are doctrinally atheistic, and both were popular for quite some time—Marxism is still popular—despite being thoroughly discredited over and over again. But there is a facet of Christianity which, outside of Marxist hellholes, tends to let atheists get along with Christians, which is that Christianity recognizes a distinction between the natural and the supernatural. Edward Feser goes into this in depth in an essay called, “Liberalism and Islam” where he explains them as opposite Christian heresies, where liberalism denies the supernatural and Islam denies the natural. It’s an interesting essay where he argues that this makes them essentially invisible to each other, especially Islam to liberalism, but that’s not my concern here. More to the point is that Islam does not have any sort of mode of co-existence with atheists in the sense that it doesn’t have any secular principles an atheist could agree with for their own reasons.

As the Distributist rightly points out, the secular west became significantly aware of Islam on September 11, 2001 and was more than a little bewildered by it. This could itself be the subject of an entire video, so suffice it for the moment to point out that people who had never thought about the supernatural had no idea of what to do with a religion that didn’t think much about the natural. And you need to know something about an idea to argue against it, which because of an accident of geography, UV intensity in sunlight, and the pigment animals use to protect themselves from UV radiation, secularists were in a bad position to do. And I think this is where the New Atheists got much of their popularity from. People who could not reject Islam specifically had to, instead, reject it generally.

At the same time, I think that the Distributist is right that dashed utopian hopes make people long for an alternative utopian promise, and the New Atheism did tend to have a sort of promise of scientific utopianism. For example, Ray Kurzweil’s book, The Singularity is Near, came out in 2006, in the thick of things. Yet at the same time the New Atheists were remarkably light on actual utopian promises; they tended to concentrate on the implied utopianism of identifying a major problem. It’s all too easy for people to confuse that with having a solution.

There are, I think, other, longer-term factors which also come into play. The New Atheism movement came on the scene as the Internet was revolutionizing culture and bringing people into closer contact with strangers than they ever had been before; the same is broadly true of college, which due to explosions in student debt had been mixing people far more than they had in previous decades. At the same time there’s a heavy marxist strain of thinking—if you can call it that—which is popular in universities. And yet proper Marxism can exist in few places besides universities, in the modern west, especially so soon after the fall of the soviet union. Communism’s legacy of death and misery was too well known in the 1990s and early 2000s for it to be respectable anywhere else. Freudianism was old and largely the butt of jokes—such as people blaming all their problems on how they were potty-trained. There was no vital atheist movement. And that vitality is very important, because we live in a world which is dying. Death lurks around every corner, and indeed every corner is itself withering and decaying. Even on a basic biological level we are heterotrophs. We don’t make our own food, even in the limited sense in which plants make their own food. And even they are only converting the energy of spent star-fuel into food for themselves. The whole world longs for a source of life which is not running out, but within the world we have to settle for the second-best of finding sources of life which are running out more slowly than we are in order to feed.

The conditions were ripe for Sam Harris and Daniel Dennet to write popular books, so that when Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens added more books to the genre it became, for a time, something growing. And growth always attracts for where there is growth there is nourishment. It’s one reason why our society has grown so fascinated with youth; young people aren’t tired.

Of course the attractiveness of growth only lasts for a while; eventually growth only signifies the swarming of people looking for life to feed off of, rather than people who may have found some source of it themselves. To borrow a metaphor, vultures will circle lions with a fresh kill, and will even follow other vultures flying down to a carcass, but they have to find something once they get there or they will just leave again; vultures don’t tend to follow vultures who are leaving. This is why the saints are so important to the church; by being so profoundly counter-cultural they continually prove that there is a source of life they’ve found even though they’re surrounded by a crowd not nearly as sure of where it is.

Clearly that didn’t happen with the new atheists, and for the most part people have moved on. Christopher Hitchens died, and his tomb is still with us. Daniel Dennett is lecturing neuroscientists that they shouldn’t tell people they don’t have free will. Sam Harris has a podcast, which is a bit like having an AM radio show. And the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science has become a subdivision of the Center for Inquiry.

I’m not sure how much longer any of the four horsemen will be remembered; no one remembers any of the atheists G.K. Chesterton publicly argued with a hundred years ago. Except, perhaps, George Bernard Shaw, who’s only remembered as a playwright. Bertrand Russell is only remembered (popularly) because of his wretched tea pot, and while Antony Flew was the world’s most famous atheist in the 1970s, in 2004 he became a deist and it doesn’t seem that anyone remembers who he was any more (he died in 2010). They don’t even know that he was the one who first proposed defining atheism as a psychological state to avoid having to come up with some reason to believe in it.

But whatever the fate of the New Atheists, I think that this appearance of vitality played a key part in the movement’s popularity, and the very fact of its fading only a few years later is key to seeing that. Things which are popular for being popular don’t last more than a few years; once everyone has jumped on the bandwagon they must do something, and if it turns out that they don’t like the music they’ll hop off again. And here’s where I partially disagree with the people who believe that Atheism+ killed the New Atheism.

For those who aren’t familiar, Atheism+ was the somewhat indirect result of what was called elevatorgate; at an atheist convention a man followed Rebecca Watson into an elevator and asked her if she wanted to come to his room for coffee and conversation. She publicly complained about this and it sparked a large conversation within the atheist community about what we might loosely call sexual morality and propriety. We might alternatively summarize it as some atheists realizing that without God to enforce good behavior, society must do it through repressive authority. This didn’t sit well with the atheists who thought that in becoming atheists they had finally thrown off the shackles of conventional morality, and long story short: the atheist community split into the feminists versus the anti-feminists. Atheism+ was created to be the feminist side, though it never went very far and last I checked the only activity consisted of a few people who got to know each other through the forums occasionally talking with each other about what courses they’re taking at school.

It is fairly incontrovertible that New Atheism was different before and after Atheism+, but I think it’s a mistake to think that Atheism+ had much of a causal effect. Just as in 2006 the time had been ripe for the New Atheist movement, by 2012 the time had become ripe for something else, because New Atheism was rotting. Actually, rotting is the wrong metaphor; it turned out that New Atheism was infertile. Once you were a New Atheist there was nothing to do but complain about God. But while supernatural movements can be eternally new since they draw their energy from eternity, natural movements must always grow old. Basically, one can only complain about God so much before getting bored. It is true that New Atheism did supply an enemy to continually fight, but one need only watch the recruiting video for the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science titled, “if you are one of us, be one of us” to see how toothless this enemy is. People who don’t believe in ghosts can only be so frightened of the ghost of Jerry Falwell. At some point one has to accept that the scopes monkey trial happened in 1925; it is history, not prophecy.

Something with more substance needed to be found, and in particular something winnable—you have to be an idiot to believe religion can be eradicated in our lifetime—but equally importantly something not yet won. Refighting old fights is safe but unexciting. This, I think, is the best explanation for the bifurcation of New Atheism into feminism and anti-feminism. A civil war satisfies both criteria rather well. But as of the time of this video, which is mid 2017, it seems that the feminist/anti-feminist civil war is itself winding down. It’s too early to write a history of it; looks are often deceiving and wars often have lulls in them before surges in violence; even metaphorical wars with metaphorical violence. But it is interesting to speculate what will happen next.

Certainly the atomizing tendency of modern technology is likely to play some role. With several hundred TV channels and several hundred thousand youtube channels, the ability to find entertainment which suits one very precisely is having an effect on making more people popular, but fewer people very popular. On the other hand people do need community; they must have movements to join. But these two things do not seem necessarily contradictory; it is possible that we will see minor cults of personality largely replace more major movements. You can see precedent for this in the church hopping which evangelicals are famous for; it’s common for people to feel a lack where they are, go looking, find a new church they fall in love with—the feeling of infatuation and novelty usually being described as “feeling the holy spirit”—stay there for a while but then acclimate and return to feeling normal, at which point they have to go looking for a new church again. (It’s a far less harmful version of what some people do with husbands or wives.) I see no reason this couldn’t happen with minor cults of personality around youtube personalities, effectively depopulating larger movements.

There are of course still some elements of traditional morality which are yet to be overturned; polygamy and incest are not yet legal in the west and at some point atheists will notice that their arguments in favor of every other overthrow of traditional morality work here too. There are people who long for a race war since they have nothing else to fight about and this could have a certain appeal to some atheists; after all, evolution could be turning the races into different species. Sure, that’s got no scientific basis, but being on the wrong side of science rarely seems to bother atheists.

Oh well, as has been said, of all things the future is the most difficult to predict. Whatever does happen, though, it is very likely to be governed by the two big problems atheists can’t get rid of: it’s not good for man to be alone, and without God, they have no intrinsic reason to get together.

Until next time, may you hit everything you aim at.

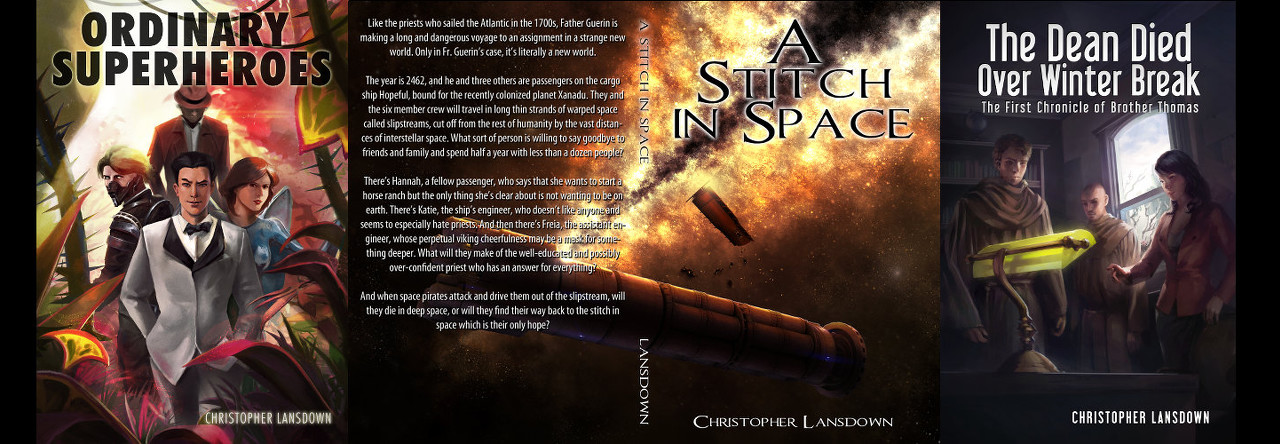

Pingback: Christopher Hitchens is Dead and His Tomb Is Still With Us – Chris Lansdown