On the fourth day of November in the year of our Lord 1983, the fourth episode of Murder, She Wrote aired. Titled It’s a Dog’s Life, it’s set in Tennessee, or at least some Tennessee-like place. (Last week’s episode was Hooray for Homicide.)

It’s set on a horse farm, specifically, as an establishing shot of horses frolicking on rolling fields, well… establishes. We also get an establishing shot of a grand house where I assume most of the action will take place.

Though I am a mite suspicious, given this camera angle, that the house is not in fact all that big and is just wide but narrow. Not that it matters; uneducated actors play professors, so there’s no reason that houses can’t play mansions.

We then get an establishing shot of some stables which I believe are actually big and ominous music plays. A figure clad all in black, including wearing black gloves, sneaks up and feeds a horse named Sawdust some kind of pill.

Sawdust eats it as ominous music plays.

When the horse has completely finished eating the pill, the camera cuts to inside the house and a string quartet is playing classic music as a large, expensive party takes place.

There are so many servants that two maids just stand around. They’ve spent something like four different shots establishing that there is a lot of money here, so that will, presumably, be important.

As the camera pans around we see that most of the people are in fox-hunting clothes. We then meet some characters. First is Trish and Anthony.

Then comes in her brother, Spence.

He tells Anthony that the family is sorry that his wife couldn’t make it.

Both Trish and Spence speak their lines like they hate each other, which is impressively poor manners in front of guests, especially for the South. We then get another relative who walks up and asks if they’re having a good fight.

Her name is, apparently, “Echo,” or at least her nickname is. She’s Trish’s niece, not sure whether Spence is her father, but I can guess how much hair spray she uses a day. Boy is it ever the 80s. She and Trish are extremely catty at each other then Spence asks for peace, if not for his sake, than for the sake of his father. At this, Trish leaves.

We then meet another of Spence’s sisters.

Her name is Morgana, and she’s very fond of her astral projectionist. Spence is appropriately rude, by which I mean he makes a gratuitous and unnecessarily mean-spirited comment which is carefully calculated to accomplish nothing whatever, then he walks off.

And then we come to the main characters.

His name is Denton and he’s a famous lady’s man about whom Jessica has been warned. They move on and Denton introduces a friend of his—the owner of a nearby horse farm, and Denton’s old drinking buddy. His name is Tom Cassidy.

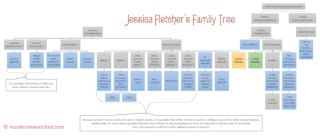

His small talk explains why Jessica is here—she’s visiting her cousin, Abby, who works on Denton’s horse farm. It also comes up that he owns a neighboring 600 acres, which is described as small, though in a tongue-in-cheek way. Tom leaves to get Jessica a refill on her coffee, and we meet Jessica’s cousin.

They make a little small talk; she tells Denton, in an English accent, to not be “an old lech.” Tom returns and interrupts the banter by saying “how about a toast?” Before he can propose one, though, Spence interrupts from across the room to say that a toast is a marvelous idea.

I find the blocking of this shot interesting. The characters are in a line to be easily seen by the camera, but it makes no sense at all as a grouping of people who had been talking to each other, and not much more as a group of people who hate each other’s company and are standing next to each other in embarrassed silence for no reason.

He proposes a toast to his father, on his 80th birthday, and many more. Morgana adds a note of affection. Denton rudely takes no notice and merely looks about and asks, “where’s that damn dog of mine?” That damn dog of his is a beagle named Teddy, who comes running from across the house. Spence and his siblings look crestfallen. I guess we can see where Denton’s children got their bad manners from. Oddly, no one else in the crowd seems to have noticed any of this, despite everyone having spoken in a loud, clear voice, to be heard.

Then a man comes in and announces, Ladies and Gentlemen: to horse.

Outside as people are getting on, Trish walks up to her horse with a champagne glass in land, takes a sip, then throws the partially full glass on the ground and mounts her horse. Abby runs over, grabs the bridle, and says, “Trish, you shouldn’t be riding in your condition. It’s dangerous to the horse.”

Trish merely tells her to go away and kiss up to Father while she has the chance. “The day he goes, Honey, so do you.”

Denton calls out to Jessica and Abby, telling him that he’s picked out their horses for them. Jessica thinks that Sawdust is for her, but he tells her that Sawdust is only fit for him; he hasn’t broken out of a trot for years (the horse). He then presses a button and tells Barnes, a security guard, that they’re ready to go and he should open the gates. Barnes, who is sitting in a room filled with monitors and controls, obliged by pressing the Gate 1 button (there are four) which opens the main gates, which we can see on video camera from two different angles.

We then get scenes of the fox hunt over beautiful countryside with swelling music. At one point Denton tells Abby, who is riding next to him, to go on because it can’t be much fun to ride next to an old slowpoke like him. Right after he says this, Trish comes up right next to Denton spurring her horse into a gallop with loud cries, which alarms Sawdust, causing him to bolt. Denton tries to reign sawdust in, but to no effect. Sawdust eventually runs at a bench in front of a hedge and jumps over it. Denton does his best during this, shouting “Tally Ho!”

The camera then cuts away during the landing.

Many people run up, deeply concerned, because this kind of thing can be easily fatal to an eighty year old man.

As, indeed, it proves to be. We cut to Denton lying dead on the ground and a moment later we screen wipe to a police deputy covering the corpse with his jacket.

After a bit of mourning, Jessica, Abby, and Tom go talk to the Sheriff, who says that it was a terrible accident but Denton led a full life. Jessica says that she thinks that Denton didn’t want to take the jump and Tom agrees, saying that Denton was under Doctor’s Orders to take it easy.

The vet is standing next to the Sheriff and Jessica asks if there’s a test he can perform on the horse. He understandably has no idea what Jessica is talking about, so Abby explains that a calm old horse like Sawdust doesn’t suddenly go wild. The Sheriff asks if Jessica is suggesting foul play and instead of answer we cut to Denton’s children getting into a police car (presumably to drive them home) and then we then cut to the cottage where Abby is staying.

Jessica is looking over papers saying to Abby, “I was so certain that there was something wrong with that horse. I feel so foolish. But, tests don’t lie.”

Abby asks, “Don’t they?” She points out that it was hours before they found the horse and there are drugs which leave no trace. Jessica acts like Abby is just being emotional, but of course she’s right. In fact, we know she’s right since we saw somebody give Sawdust a pill shortly before the hunt. This is an interesting choice, both in the showing us and in having Jessica act contrary to what we know to be true. She was wrong when she felt foolish, but we know that she’s now being foolish. Perhaps this is meant to make Jessica relatable by “not being too perfect”? Another possible explanation is putting the investigation on hold in order to get the episode to last the approximately 47 minutes it needs to.

Abby then goes on about what a great man Denton was, but underneath it all he was unhappy because of his selfish relatives.

Which brings up an uncomfortable issue: if Denton’s children are all awful, why didn’t he raise them better? I know that children are their own people and make their own decisions. Great sinners can be the children of great saints, and great saints can be the children of great sinners. That said, being raised well helps and being raised badly does make being a saint harder, and if all of a man’s children are terrible, it’s only fair to ask whether he raised them in a way that made being good, hard.

Anyway, there’s a bit of odd dialog which implies that Abby was in love with Denton and Jessica offers to stay with her for a few days. Abby asks her to stay until the will is read.

Which is necessary to keep Jessica around for the investigation, of course, but it’s really weird. Why would Abby be sticking around for the reading of the will?

We then cut to the day of the reading of the will, or maybe it’s the hour. The exact amount of time that’s passed isn’t specified, and all we get by way of that is an establishing shot of the front door with a black wreath on it.

Spence and Trish fight a bit, but they do establish that “Boswell,” presumably the family lawyer, is expected any minute. After some more bickering, he comes.

Denton’s will is done on video. This was quite a new technology in 1983. The first VHS player came to the United States in the summer of 1977 and they would become popular pretty quickly, but consumer video cameras that recorded onto VHS took longer. The first consumer ones actually came out in 1983. A rich man like Denton could afford to rent professional video equipment to make his will, but the thing would have felt very cutting edge at the time. Boswell describes it as “cutting edge will technology.”

Denton starts out by saying that it’s all legal as hell, so don’t get any ideas. This sets the tone. He then has a hate message for each of his children and grand daughter (it turns out that Morgana is Echo’s mother). That parting spite finished, he gets down to brass tacks.

He gives a shotgun that Tom admired to Tom (his old drinking buddy) and there are cash gifts to each of the servants with something extra for the guard. All of the paintings in the house go to the national gallery. He then says, gleefully, “that’s right, Children, a fast three million in oils now on the way to Washington.” Bosley looks remarkably smug at this.

There’s so much wrong here, but I don’t think that we’re supposed to notice.

Anyway, the rest of his estate comes to about fifteen millions dollars and, except for a modest family trust, goes to his dog, Teddy. Denton’s descendants are upset at this but Boswell assures them that they won’t be able to break the will and if Teddy dies of anything but natural causes, the entire fortune (including the family trust) goes to the SPCA.

And on that bombshell, we go to commercial break.

When we get back, Jessica is on the phone with Ethan, telling him she’ll be gone for a few more days, and adds that Abby is convinced that somebody murdered Denton. And Jessica is afraid that she just might be right.

We then move to a scene where Abby has a pointless fight with Trish, but it is at least established that Teddy is her employer and as such only Marcus Bosley can fire her, and she’s not going anywhere until she finds out who killed Denton.

Interestingly, Morgana warns Abby to be careful of Trish. She does it with some astrological mumbo jumbo, though, so Abby takes no notice. (I say mumbo jumbo because really doubt that the writers got the astrology right, quite apart from my belief that there is nothing to astrology.)

Then there’s yelling, a horse runs out, and Spence is in a horse stall defending himself from Teddy. The scene shifts to the vet examining Teddy and holding up a test tube of clear liquid and saying, “giving this stuff to a dog is like giving loco weed to a horse,” though when asked he didn’t find any in Sawdust. The vest asks who Teddy bit, since he found blood on his collar. The Sheriff then pulls up with a man in the passenger seat who identifies Teddy as his assailant.

In the next scene Marcus Boswell is on the phone with Abby, telling her that Teddy has been released on his own recognizance and she can pick him up from the Sheriff at any time.

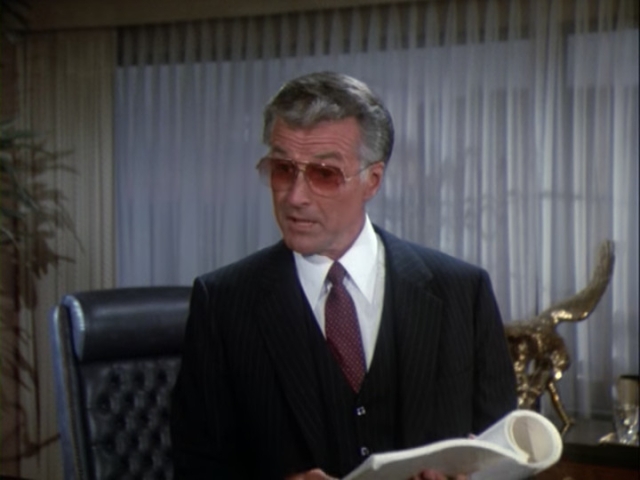

Jessica and Abby talk about the situation and Jessica thinks that they need to talk to Marcus to get more information. The shot of them waiting in his office is interesting, especially with how large and posh the office is.

To drive the point home, Jessica remarks that Marcus has done very well working for the Langley estate.

After a minute, Marcus and another lawyer come out. The lawyer says that he could drive a freight train through “that loophole” and Marcus replies that his clients need to consider the costs; it could be a long and bloody battle. Then Morgana walks out of Marcus’ office and says goodbye.

To highlight just how much of a suspect Marcus is, as Jessica and Abby enter the office, his secretary tells him, in an exasperated tone, that it’s his broker and it’s the third time he’s called today. That could, of course, mean anything—and in real life would most likely mean that the broker was trying very hard to sell something to Marcus. In Murder, She Wrote, though, it almost certainly means that Marcus is in financial trouble.

Marcus’ office is even more impressive than his waiting room:

They get down to business. Jessica asks about whether the man who Teddy bit has filed a lawsuit and Marcus says that while he’s made noises, he hasn’t yet and Marcus intends to head him off (whatever that means). They then switch subjects to the will, and the fancy lawyer’s supposed loophole is the question of “sound mind.” Not Denton’s mind, but the dog’s. If a court rules Teddy mentally incompetent…

He doesn’t finish his sentence and I can’t imagine what the end of it might be. You don’t need to be of sound mind to inherit under a will. If Teddy was ruled not of sound mind, he’d require a guardian appointed for him. But he’s a dog, so he needs a guardian anyway. This could only be an issue of the dog literally, rather than figuratively, inherited the money. But that would be nonsense. Animals can’t own property. I assumed that what Denton meant was that a trust was set up with Marcus as the administrator for the benefit of Teddy. That would certainly be, in colloquial English, Teddy inheriting, but it would make legal sense and the fact that Teddy requires a guardian would be irrelevant. I can’t believe that the episode is trying to claim that a dog has literally inherited money and land. You don’t need a loophole, that would be simply impossible. You can only give your property, in your will, to some kind of legal entity capable of owning it. (It can be a fictional person, as in the case of giving it to a corporation, but it has to be some kind of legal person.) I wouldn’t bring this up except that they’re actually making a plot point of it having been done in an impossible way.

Anyway, Marcus says that Denton’s descendants won’t win, but it might take long years and a lot of legal feels to win the battle. He leaves off how much this would benefit him and also explain away the missing money he’d embezzled. (I’m just guessing about that last part, of course.)

He’s interrupted by yet another call from his broker, who insists on speaking to him. Why his secretary seems to work for the broker and not for her employer is not explained. Anyway, he takes the call and after some embarrassing half-phrases, he promises his broker that he’ll send a check today and even put a stamp on the envelope this time.

After hanging up, Marcus tells the women to never, ever buy stock touted by Spencer Langley. His only consolation is that Spencer bought more of it than Marcus did.

This can, in no way, explain why his broker needs a check. No matter how badly a stock does, you’ve paid all of the money when you bought it and can only recoup some money, even if far less, after its sale. Between the purchase and the sale, you do not use money for anything. The only possible way for stock transactions to need cash quickly is if you sold futures and need to buy the stock to cover the future. There’s no way that’s what happened, though.

Jessica only picks up that Spencer is in debt, and Marcus replies, “right up to his Adam’s apple.”

This is not even slightly how stocks work. The only way for a stock doing badly to sink you into debt is… well, there is no direct way. You simply have to take on the debt separately. But you can take on debt in order to buy stock, which you intend to pay off and get profits from when you sell the stock at a higher price. But in that case it would be your banker, not your broker, who is calling you demanding money.

I’m really not sure which is more ridiculous: a dog literally inheriting property or a broker calling demanding money because a stock you bought is doing badly.

Oh well.

We then get a shot of the moon at night to establish that it’s nighttime. Since all pictures of the moon are basically the same, I’ll use one that I took instead of a screenshot. It’s not exactly the same, but you get the idea, and I only use screenshots when they’re necessary for my commentary on the episode:

We then cut to Barnes, the security guard, sitting in front of his collection of monitors. I wonder if the idea is that he lives here in the cave of security cameras on twenty four hour duty. No wonder he got something extra from Denton’s will.

He then hears a sound and the door and goes to open it. It’s Teddy. Barnes says something about “like clockwork,” implying that Teddy always comes to be with Barnes at this time. “I guess you know you’re safe in here,” Barnes explains.

He then notices Trish’s car pulled up to the front gate. He comments that she shouldn’t be allowed to drive. On the security camera she stumbles out of her car and buzzes for Barnes to open the gate. He presses the button and as the gate begins to open she falls down with her head between the gates that just opened.

Barnes puts Teddy down saying that he needs to go check that she’s OK. He leaves, with Teddy remaining behind on his chair.

When Barnes gets near, the gates start to close. Barnes runs to try to save her but he’s too late. The gates crush her head (off camera, of course). We then cut back to Teddy in the guard room, partially standing on the console, wagging his tail.

And on that bombshell, we go to commercial break. (I think that the implication is that Teddy pressed the button and killed Trish.)

When we get back from commercial break, we’re outside by the gate while a bunch of police cars are in the area, presumably investigating. Inside the guard room, someone is dusting for fingerprints on the gate button.

Then in a large room with the Sheriff and the family gathered, Morgana says that she saw her sister’s ghost rising from her earthly form and crying like a morning dove. We get some other backstory about her aura thriving on moonlight and such-like, but we also learn that her bedroom has the only clear view of the gate, and she looked out because she heard a car’s horn.

The doorbell rings and it’s Marcus. He’s come as soon as he heard, for some reason.

Then the Sheriff’s deputy comes in and tells him that they found a print on the gate button, but not a fingerprint—a paw print.

Given that they found it by dusting, blowing away the dust and then using tape to pick up the dust which remained after being blown away, I guess we’re supposed to believe that the digital pads on a dog’s paws leave oil residue? I can’t easily find out whether dogs even have oil pores in their digital pads (they do have sweat pores) but my experience of dog feet is that they are very, very dry. I really doubt that they have sufficient skin oil as to leave enough residue to be able to lift a paw print. It’s not impossible, so far as I know, but it’s still a bit… far fetched. And even so would leave entirely open the possibility that someone used Teddy’s paw to press the gate button so as to leave no fingerprints. It can’t be supposed that Teddy understood that pressing the button would hurt Trish as a human could.

Anyway, there’s some arguing and bickering over how this gets rid of the will—I guess everyone has forgotten that if Teddy dies of anything but natural causes, all of Denton’s money goes to the SPCA. Though I don’t see how that would come into play since the dog would likely just be put into prison for life—even if he got sentenced to death, it takes so long to work through the appeals and so on that he would die of natural causes anyway.

I can’t believe I’m actually thinking that through. Why is this episode demanding that we take a dog seriously as a human being?

Anyway, Marcus shouts, “Sheriff, you cannot possibly believe that a dog is capable of murder!” At that, Abby says, “of course not. He’d have to be trained.” Then everyone stairs at her since she’s an animal trainer.

The scene shifts to Jessica going down to the front gate. She runs into Tom driving up in an old blue pickup truck. He asks how the family is doing then says he came as soon as he heard on the police band on his CB radio. He then drives on up to see what he can do to help.

Jessica wanders on down and meets Will, who’s trying to get the victim’s coat into a large plastic bag. Jessica offers to help and examines the coat in the process. Will gratefully accepts the help because he feels that the coat requires a “lady’s touch” to fold.

As you can see, the deputy is a young man and Jessica comes on with a matronly tone. This part actually feels quite realistic. Also, Jessica’s examination shows that the coat is quite new but the seams are split, just like her “car coat.”

After a bit of small talk, Jessica then walks around, examining the ground. After that she goes and interviews Barnes in the security room.

He left Teddy alone and the door automatically locks when it’s closed. He’s got the only key, and Teddy was left alone in the room. When he asks Jessica if she really thinks that Teddy pushed the button, she replies that she’s quite sure of it. She asks if he heard anything unusual while he was on his way to the gate and he replies no, just the usual. Crickets and a night bird calling.

She then asks the way to Morgana’s room.

Morgana’s room does, indeed, have a decent view of the gate. While Jessica is looking, we also hear some music which suggests that this is an important clue.

Jessica then joins Abby in the kitchen for tea. (When stressed, the English always go for tea.) When Marcus comes in to fetch ice because everyone in the main room needs a drink, Jessica notices that he has a nasty grease mark on his trousers. It’s important to the plot because we get the kind of closeup necessary in 1980s televsion to make sure we can see the clue even if there’s interference in the signal.

He says that he had a flat tire on the way over and he supposed that he got some grease off of the jack. A jack is a device for lifting the car up so that one can put the wheel on and take it off, which a human could not possibly do if the weight of the car is still on the tire. They look something like this:

(Not shown is a bar that goes through the hole and is used to give the mechanical advantage necessary to turn the screw.)

There is no realistic way those grease marks came from a jack. Given that this episode has several impossible things already, I’d have figured that this was yet one more unrealistic thing, but the fact that they gave us a close-up suggests that it’s meant to be a clue and not a plot hole.

Jessica then asks where he got it and how long he stopped. He figured about half a mile away and he stopped for about twenty minutes. Jessica asks if that means that anyone who left the house would have had to pass by him.

Marcus says that Jessica is right, but that no one passed by him. Abby says that that means that the killer had to be someone in the house, and Marcus concurs.

After he leaves, Jessica asks Abby how one would go about training a dog to press a button. The answer is endless repetition, and the command could be anything. A voice, snapping your fingers, a whistle—at that Jessica perks up. A whistle was just the kind of thing she had in mind.

Some bickering later, Jessica is forced to explain her theory to everyone, including the Sheriff. Basically, it’s that someone impersonated Trish—whoever got out of the car never spoke on the intercom. At this point Trish was inside the car. After a minute the person impersonating Trish got up, dragged Trish (who was drunk or unconscious) to the spot where her head was in the way of the gate, then gave Teddy the signal over the intercom.

The Sheriff then asks if a whistle like the one he’s holding would do it. When Jessica says that it’s possible, the Sheriff asks if anyone in the house has the initials A.B.F. and Abby replies “Abigail Benton Freestone.” The Sheriff adds that they found the whistle down by the driveway.

The scene then shifts to the Sheriff’s office, where both Abby and Teddy are in jail.

I really don’t know what, if anything, we’re expected to take seriously anymore.

We cut from Abby bemoaning her fate to Teddy to Jessica being angry at the Sheriff. After she insults him and complains at him, he says that the inquest is on Friday and until then Teddy is going to be held as an accessory after the fact. Which is not what he would be. An accessory after the fact is somebody who did not take part in the crime but did take part in trying to help the person who committed the crime to evade justice. Even if you ignore the fact that Teddy is a dog, that’s not what he did. He took part in the commission of the crime, which would make him an plain old accessory. At this point I’m starting to wonder if they’re just getting things wrong on purpose. I guess we should count our blessings that on the fox hunt they rode the horses and followed the hounds, rather than riding the hounds and having the horses follow the scent trail.

In the next scene Jessica is given a lift back to the house by Marcus. She has him drop her off about a half mile away from the house, saying that she needs some exercise. He drives off and she looks at his tire tracks.

I’m going to guess that the issue is that both tires are bald, or else both tires are the same size, meaning that Marcus did not, in fact, have a flat tire recently. It’s a bit of a problem for this clue to show us that because we’re only seeing the marks of two tires (kind of next to each other, from when the car was turning slightly to get back onto the road). The flat could have been on the other side of the car, which stayed on the road and whose tracks we don’t see. Marcus never said which tire went flat. However, the fact that they’re showing this to us pretty much means that the flat tire had to be disproved. Things are not looking good for Marcus; we’ve had two close-ups on clues related to him.

As Jessica is looking around, the nice young deputy Will shows up and asks her what’s up. He asks if she’s looking for something and she said just a hunch. She asks if he has one of the Sheriff’s new metal detectors and he says that he can get it. She’s looking for a bicycle clip. A plain, ordinary bicycle clip. He doesn’t know what she means and she says that he’ll know it when he sees it.

Later on Jessica is mounted on a horse when Echo comes up. She asks where Jessica is going, and she says that she’s going to see a man about a dog bite. (Jessica asks about Spencer, whose horse is missing.)

We cut to Potts operating a chainsaw while his arm bandage is on a shotgun. Jessica rides up the horse then sneaks up and steals Potts’ arm bandage. When she gets back to her horse it’s actually Spencer’s horse, he took the liberty of putting her horse in the stable. He then calls Potts.

Potts and Spencer interrogate Jessica at gunpoint. Potts is in favor of killing her and hiding the body, but she talks him out of it, saying that his little scheme of fraud will hardly be noticed once she reveals who killed Trish. There’s a bit of bickering, but then we cut to a court house. Well, some kind of building in which court is in session. It feels more like a gymnasium.

I’m not sure what it’s supposed to actually be. When the deputy brings in a speaker on a long wire, the judge—or whoever he is—asks what’s going on and Jessica says that this is part of her presentation. I suppose that this is actually supposed to be an inquest, and I must confess that I need to do more research on them to get a sense of whether this set makes any sense. It doesn’t feel like it, and from the rest of this episode I would guess that it doesn’t.

The judge indicates that the proceeding is going to begin with Mrs. Fletcher acting as an amicus curiae. He then says that, for the yahoos in the back, that’s a friend of the court.

Jessica get up, makes an introductory remark, and then says that to keep this short she’s only going to call one witness: Teddy.

Sure. Whatever. I don’t see any way to care at this point that an Amicus Curiae presenter (they’re more normally written briefs, but this is TV) would have no right to call witnesses. She’s calling a dog as a witness and everyone is OK with it, so I guess we’re just in clown world.

Teddy is carried in by a deputy and put in the chair next to the small table. Jessica then has the deputy blow on the whistle that was found by the gate. No one hears it but Teddy because it’s an ultrasonic whistle. She then has the deputy go into the other room and blow the whistle over the speaker. After he says that he blue the whistle, Jessica notes that Teddy didn’t react, because the whistle is above the range of the speaker. She actually says “any loudspeaker” which is probably wrong, but it probably would be above the range of a speaker system used in a security system, even back in the 1980s when they were all analog. (Most modern digital systems have a hard cutoff at either 22.05 or 24KHz, while according to Wikipedia most dog whistles are in the 23-54KHz range, so for most dog whistles it would be impossible to record or transmit them over normal digital systems. I only bring this up because it relates to adapting this kind of idea to modern stories.)

Jessica then explains that it was Marcus—he desperately needed the money years of litigation would bring him. He persuaded Trish to drug Denton’s horse by lying to her about whether she would inherit under Denton’s will. Trish was, of course, furious when she found out the truth, but he had prepared for this and trained Teddy long in advance.

She then starts interrogating him. Does he own a bicycle, does he ride out by the Langley manor, etc. When he denies having ridden by the Langley manner on the night of Trish’s death, Jessica then confronts him with the bicycle clip. While he quite reasonably points out that the bicycle clip could have belonged to anyone, she counters with her observation of the characteristic grease stains of a bicycle chain being on his pants that night. When he claims it came from changing a tire as he said that night, she counters that all four of his tires had identical tread, while a spare tire should have had deep, new tread. She then suggests settling the matter by looking in his trunk.

Before he can answer, she calls out to Will to “go ahead, please” and places the gate button next to Teddy. When a mockingbird whistle plays over the loudspeaker, Teddy presses the button several times, then goes over to Marcus and looks to him for a treat.

Jessica in fact asks him, “why don’t you feed him his treat? Just like you did when you trained him to help you murder Trish.” Marcus looks around and seeing no way out sinks into a chair, crying, his face in his hands.

Back at the Langley manner Jessica and Abby are talking. Abby confesses that she doesn’t understand why Marcus did it and Jessica points out the obvious that he would have found a hundred ways to bleed off as much money as he needed from Teddy.

Then Tom drives up and takes Teddy, while Abby and Jessica say that Teddy will be very happy in his new home. After a bit of small talk in which he promises to do absolutely nothing for Denton’s children, he drives off with Teddy in the back of his pickup truck and we go to credits.

What an episode.

I have no idea what to make of this—is it supposed to be a parody? It’s early enough in the first season that they may well have tried several different kinds of episodes to see what felt right or hit it off with fans. If this wasn’t meant to be a campy parody-type episode, a lá the 1960s Batman series starring Adam West, then this was a really stupid episode. If it was supposed to be a campy parody, it wasn’t very funny.

I really don’t know what to say about it.

If we ignore all of the asinine stuff about the dog actually inheriting the money directly, being charged with murder, etc. we do have the skeleton of a decent murder mystery. The family lawyer needed money and convinced one of the millionaire’s heirs to murder him, then when she found out she wasn’t inheriting, he murdered her. That’s pretty solid. Training a dog to do it isn’t wonderful, but it does have a bit of a golden-age “clever twist” feel to it.

Unfortunately, the dog training doesn’t really make sense in this story. For one thing, how on earth did Boswell train Toby to scratch on the door every night? He’d have to be there to do it, and are we really to believe that the security guard didn’t notice Boswell there giving Toby treats every time he scratched on the door? For another, dog training isn’t a context-independent thing. When you train a dog to a command in a place, it mostly only responds to the command in that place. This is why police dogs get trained to a command in about twenty different contexts—that’s what’s necessary to get them to respond to a command in any context. And the specificity of pressing a specific button out of a collection of buttons—that’s doable, but it would basically require training Toby in the security guard’s office. All of which might possibly be a stretch of the imagination if Boswell lived on the grounds and had constant access to the contexts necessary to train Toby. As somebody who did not have regular access either to Toby or to the grounds? That’s just not how dog training works.

Of course, I don’t know why I’m bothering with that because this is an episode where a dog inherits money and is arrested for murder.

Ultimately, I’m inclined to write this episode off as an early episode where the writers hadn’t decided on the tone for Murder, She Wrote yet. It had some nice visuals and the hint of a decent mystery, but if this was what Murder, She Wrote was generally like, well, I don’t think I’d be writing these reviews, forty years later.

Next week we go to Virginia for Lovers and Other Killers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.