Clue, which goes by the name Cluedo in Britain, is a very fun game that has had an enormous number of versions and a very enjoyable, if quite odd, movie based on it.

If you don’t know, the presmise of Clue is that Mr. Boddy has been murdered in a mansion by one of the six guests: Mrs. White, Mr. Green, Mrs. Peacock, Professor Plum, Colonel Mustard, and Miss Scarlet. (The characters in the screenshot are in that order, left-to-right.) Each player (the game works for three to six players) plays one of the suspects and goes around the board collecting clues, and trying to figure out who killed Mr. Boddy, in which room they killed him, and with what weapon.

This may make a little more sense if you look at the board:

When you consider the problem of trying to make a murder mystery board game that remains interesting when played more than once, the game mechanic is rather brilliant. Each suspect, room, and weapon has a card. You group each kind of card together and shuffle them, then you randomly pick one of each kind and, without looking, put it in the solution envelope (placed in the center of the board). You then, to the best of your ability, evenly distribute the rest of the cards (now combined and reshuffled) among the players. They then take turns rolling a die and moving that many squares, going to the various rooms of the mansion. From a room you can guess that room and any player or weapon that you like (officially, you “suggest” them); you then go counter-clockwise and the first player that has one of the three shows one of the cards that matches the guess to the guesser (without revealing it to the other players). Who answered the query gives limited information to the other players, depending on what they already know and what cards they have, giving material for logical deductions. When a player thinks they know the solution they state it as an accusation, then (without showing them to the other players) look at the cards in the solution envelope. If they’re right, they win. If they’re wrong, they’re now out of the game except for answering the suggestions of other players. If everyone understands the rules and pays attention, the game moves quickly and is a lot of fun, since you stand to learn something on every person’s turn. Indeed, if you’re good, you learn more from the rest of the players’ turns (taken together) than from your own.

The game was developed by Anthony E. Pratt in 1943 while he worked in a tank factory during the second world war. He was inspired by a game called “Murder” that he and friends would play during the inter-war years where people would sneak around rooms and the murderer would sneak up behind them and “kill” them. That and the great popularity of detective fiction at the time.

It would take a number of years before it was actually published, though. He brought it to Waddingtons, a British maker of card and board games founded in 1904 as a general printer that got into games in 1922. It was eventually bought out by Hasbro in 1994. Waddingtons made a number of changes to the initial concept, most of them being to simplify it a bit (such as reducing the number of characters down to six). Something I find very interesting is that its initial marketing focused on the detective aspect, to the point where they even licensed Sherlock Holmes’ likeness from the estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle:

Another change by Waddingtons was the name. Pratt had simply called his game “Murder,” after the house party game that he and his friends used to play during the inter-war period. The name Cluedo was a portmanteau of Clue and Ludo, the later being the popular name in England of a board game Americans tend to know better as Pachisi. (Ludo is Latin and means, “I play.”) Since Ludo was not well known in America—the game was licensed to Parker Brothers for distribution in the US—the name was shortened to Clue for the American version.

There have been many editions of Clue since the original, many of them updated and more modern. The one that I own (pictured earlier) is a “classic” edition which comes in a wooden fake book. (It was a gimmick used for a variety of classic board games but works particularly well for Clue.) There’s a great deal to be said for the classic version because the game is so suggestive of the golded-age detective stories which inspired it and upon which it is (ever so loosely) based. The dinner party in a mansion is rather tied to this time period because people don’t really have dinner parties anymore. There’s so much more to do, these days.

This was actually an interesting needle that the movie needed to thread. Why would there be a dinner party with such different people in a large house? The movie partially solved this by using an earlier time period—the mid 1950s (it was specifically set in 1954). The other thing it did (spoilers ahead) was to make them all blackmail victims who were meeting each other for the first time. This was an interesting approach to giving everyone a motive for killing Mr. Boddy.

The other problem that the movie had, and only partially solved, was how on earth can it be a mystery whether a man was shot, stabbed, strangled, or bludgeoned to death? This is a place where, I think, the movie could have done a little better. It is a solvable problem, at least in the context of trying to solve the crime before the police arrive. (The solution would be to have people trying to frame others and so attack the fresh corpse with someone else’s weapon.)

The movie is rather interesting for another reason, though: it has a nod towards the replayability of the board game. Instead of having a single ending, it actually has three endings. As a gimmick during release, each movie theater was sent one of the endings at random. Fortunately for the recorded version, it was released on VHS long before DVDs were a thing and so they had to figure out something to do for the VHS version. What they came up with was to present one ending, then put in a silent-movie style text cards saying:

And then, after the second ending, we get:

I really like this version. It has style, it’s cool, and it also is an interesting way of poking fun at how mysteries are often indeterminate until some clinching evidence at the reveal. But it also is a great nod to how the board game doesn’t have a single solution.

I don’t know how much the movie led to interest in the board game—I can say that it did for me, but I don’t know many other people for whom it did. But I do know that there were versions of the board game which used art from and based on the movie. And in the 1980s it was kind of a big deal to have a feature film based on your thing—not many things did.

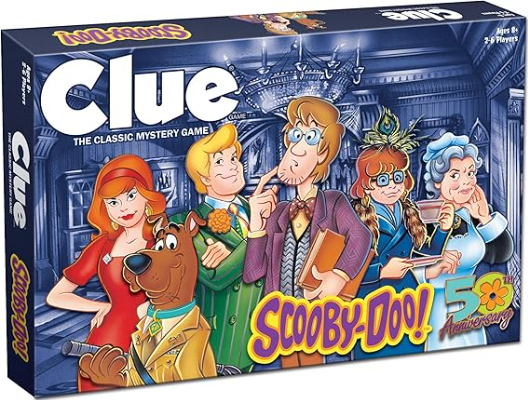

And that does point, too, to the answer to what got me looking into this in the first place: the game changed its art and style fairly often throughout its history. There were, in the last few decades, a rash of various brands trying to distance themselves from their history and from the past, but Clue was not, so far as I can tell, meaningfully caught up in that. It started with an aesthetic that was, at the time it was developed, relatively modern (except for the Sherlock-Holmes-alike, but that was a specific character rather than meant to be referencing a time period) and it changed throughout its history in ways that were contemporary. It also had a variety of tie-in versions, perhaps the most obvious being the Scooby-Doo version (still for sale on Amazon as of the time of this writing):

Having said that, I’ll take the classic version any day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.