On the sixth day of October in the year of our Lord 1985, the second episode of the second season of Murder, She Wrote aired. Titled Joshua Peabody Died Here… Possibly, it is set in Cabot Cove. (Last week’s episode was Widow, Weep For Me.)

The scene opens on a construction site:

But all is not well here, as there’s a great deal of noise from the many people who are protesting it. After some general milling about and shouting, we meet one of the characters who is organizing the protest:

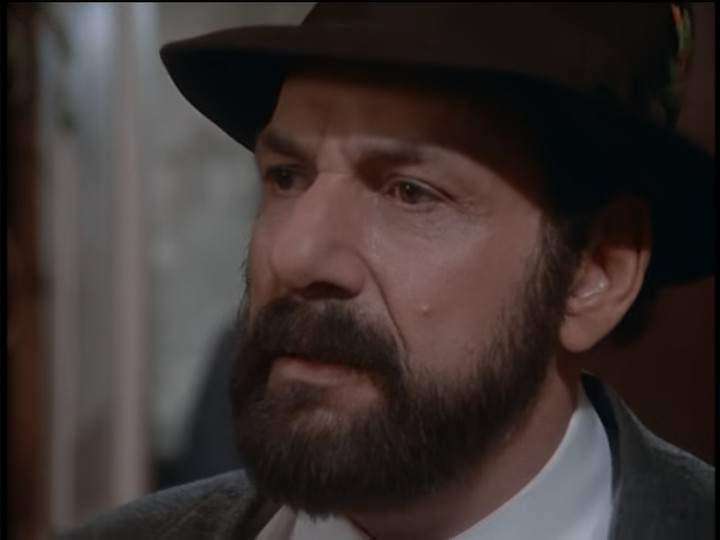

His name is David. We see him here leading everyone to sit down in front of the truck driving into the construction site.

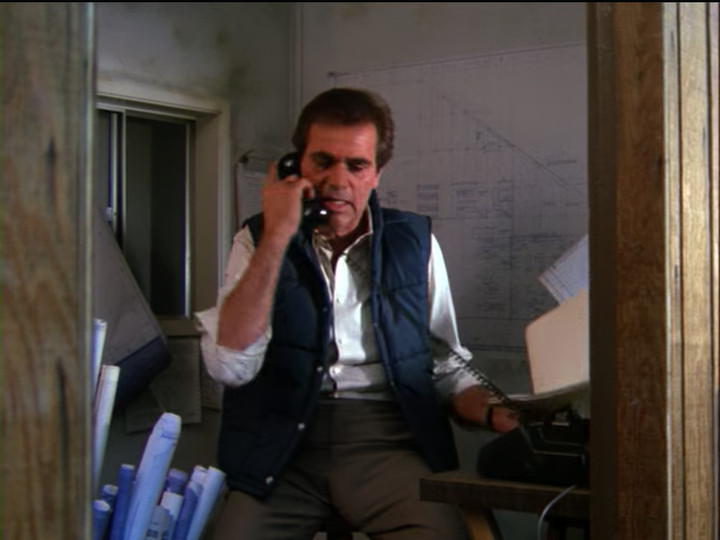

We also meet Kowalski, who is in charge of the construction, and Harry Pierce, who is a real estate agent but is generally involved in promoting the sale and development of real estate as the plot of an episode may require and is an agent of the developer in some vague, unspecified way.

Harry Pierce is played by John Astin, by the way, who is best known for playing Gomez Adams on the TV show The Addams Family. (The Addams Family ran from 1964-1966, so by the time of this episode it had been almost twenty years since Astin had played the character.)

Harry goes over and talks to David. We establish that Harry thinks that this will be great for Cabot Cove because of all of the tourists it will bring in, though not why on earth he thinks that a twenty story luxury hotel will bring tourists in. Hotels are not usually destinations in themselves and Cabot Cove hardly seems like the kind of place to bring in more guests then residents given how little there is to do here.

David claims that Harry snuck the hotel by the zoning board when half the members were out of town. Harry takes exception to this, pointing out that they had a qorum. Which is a pretty reasonable point—quorums exist for a reason.

Sheriff Amos Tupper then arrives to deal with the uproar.

There isn’t time for a discussion, though, before somebody calls out, “Hey look! Down there!” and everyone runs to look down there.

Presumably it wasn’t the camera that they were looking at, but we don’t find out because the scene then shifts to Seth’s house:

I love the “& Surgeon” as if you might be walking along the road needing an organ removed but not know where to go.

Seth replaces Captain Ethan Cragg as Jessica’s close friend for Cabot Cove episodes. Supposedly this was due in part to Angela Lansbury pushing for it because she didn’t think Jessica had anything in common with the uneducated and taciturn fisherman who often took care of her plumbing, but the town doctor does make a certain amount more sense than a fishing captain since the doctor can be called in to check out the episode’s corpse and thus is a natural part of the episode rather than a fifth wheel merely there for comic relief.

Anyway, we’re introduced to their relationship by Jessica being there looking like she’s a patient:

But despite her back pain, she’s actually here for sympathy because she’s having trouble with her book.

Arthur is trapped in the belfry. His brother Charles is on his way to the minister. Alice is in the shower. And the killer is climbing up the stairs…

Seth interrupts to ask Jessica, “Exactly how long have you had these symptoms?”

Jessica doesn’t get to respond because Amos barges in and interrupts, saying, “Listen, Seth. If you can tear yourself loose from killing off your patients you gotta get over to Main Street quick, and bring your bag.”

I’m not sure how this construction site, which doesn’t seem to be next to anything, is on “main street,” but in any event Amos drives Seth and Jessica to the construction site, where we finally find out what everyone was looking at in the hole that is, presumably, where the foundation for the hotel will one day be laid, once they dig past the loose dirt and hit rock.

Amos figures that this has to be the remains of Joshua Peabody (Cabot Cove’s most famous revolutionary war hero—though whether he existed at all is the subject of debate, with Amos being strongly on the pro- side while Seth is partisan to the con- side).

When Harry tries to hurry things up, Jessica points out that, while it could be Joshua Peabody, it could also be a murder victim and this the site of a murder. (The skull has a large hole in it.) Amos decides that she’s right as soon as he realizes that this means that he can make the construction crew refrain from disturbing the bones.

David then goes home and we get some family life—his kid got in a fight with another kid in the gym because the other kid was making fun of David. His wife wishes David could have stayed out of these kinds of protests just once. Etc. He then gets a call from Jessica because he’s an antiques dealer. She’s examining a long rifle and reads him the inscription, “Phelps and Handley, Liverpool.” David tells her that it was issued to the British army starting in 1762. (Amos seems to regard this as evidence in favor of his Joshua Peabody theory, though why a revolutionary war soldier would have a rifle used by the British is never considered.)

The scene shifts to the other end of the call, where Jessica, Seth, Amos, and Harry are in Seth’s office as Seth takes measurements of the bones. There’s a bunch of arguing and yelling—I’m not sure why TV writers think that yelling makes for good TV—but the important part is that Jessica suggests that the corpse might be quite a lot more recent than Joshua Peabody. She suggests one of the militiamen from the recreations of the battle of Cabot Cove that used to be held until twelve years ago.

We then get a scene with Harry, Kowalski, and Henderson Wheatley (who is the developer putting up the money for the construction of the hotel). There’s some bickering amongst them which is unpleasant to watch, then finally they’re interrupted.

It turns out that they’re having this meeting in the hotel lobby, because we meet some more characters (they were the interruption) as they walk in to check into their rooms:

Her name is Del Scott, and she’s some kind of reporter. A hard-boiled one, specifically, who casually insults the subjects of her reporting (she repeatedly calls Wheatley a crook). The two men behind her are nameless and we never see them again.

We then get a scene of Wheatley, outside, ordering his lawyer around a bit, culminating in telling him to, by noon, get a court order to resume work immediately.

And on that bombshell, we go to commercial. Had you been watching back in 1985, you might have seen a commercial like this:

When we come back, we see Jessica coming out of the Cabot Cove courthouse for some reason.

As she leaves, Del Scott stops her on the street and asks her opinion, as Cabot Cove’s most famous citizen, on Henderson Wheatley’s latest construction project. Jessica replies that she’s famous for her books, not for her opinions and, in any event, this is a town matter, not one of national interest.

As they walk, Del tells Jessica about how she’s hated Wheatley for his sub-standard construction ever since she was covering the weather in Pittsburgh (that seems like the kind of detail that often comes up later—especially because as someone covering the weather in Pittsburgh she’d only have reason to hate Wheatley if a relative was killed in one of his buildings or something like that). Jessica suggests Del talk to someone like David Marsh, who would be far more eloquent on the subject than Jessica. She already tried, though, and Marsh declined. He even requested that they not film him at the construction site, though his request was too late. (This suggests that Marsh doesn’t want to be seen on national TV, perhaps because he’s a wanted fugitive who’s living under a false identity. Alternatively, that he’s someone in the witness protection program.)

The scene then shifts to a couple of hayseeds who are telling Amos that the bones don’t belong to Joshua Peabody, but to Uriah Pickett.

When Amos asks who they’re talking about, the man says that Uriah was a farmer from over “at the Blue Hill.” He disappeared fourteen years ago come April, same time as the fighting, as she recalls. Amos then replies that Uriah didn’t disappear, he ran away to Portland with a red-haired manicurist who used to work for Thelma Hatcher. (How he knows this so clearly when a moment ago he didn’t know who Uriah was, he does not say.)

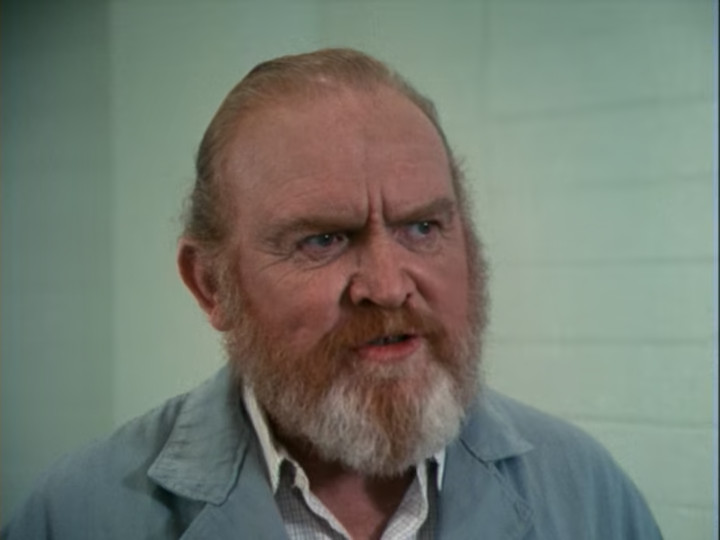

This meeting is then interrupted by Ellsworth Buffum from Kennebunkport.

He’s the vice-president of the Joshua Peabody Society. He’s hear to take charge of the last remains of Joshua Peabody.

Amos is interrupted before he can respond by an important phone call and has to leave in a hurry.

The emergency turns out to be fighting down on the construction site. Or, rather, protesters standing in the way of heavy equipment and people shouting at each other. When Amos arrives the lawyer hands him the court order that construction should resume immediately. Ellseworth Buffum then calls attention to an injunction which he has from another court stopping all work until a historical examination is completed.

Later, at dinner in Jessica’s house, Seth and Jessica discuss the dinner Seth made (Jessica says it has too much basil while Seth says that there’s no basil in it) and also the corkscrew Jessica has, which Seth dislikes and Jessica says works perfectly well if you know how to use it. Also, Jessica couldn’t find anything in historical records to prove that Joshua Peabody actually existed and Seth says that the skeleton was of a man with a bad back—a problem with his fourth and fifth vertebrae.

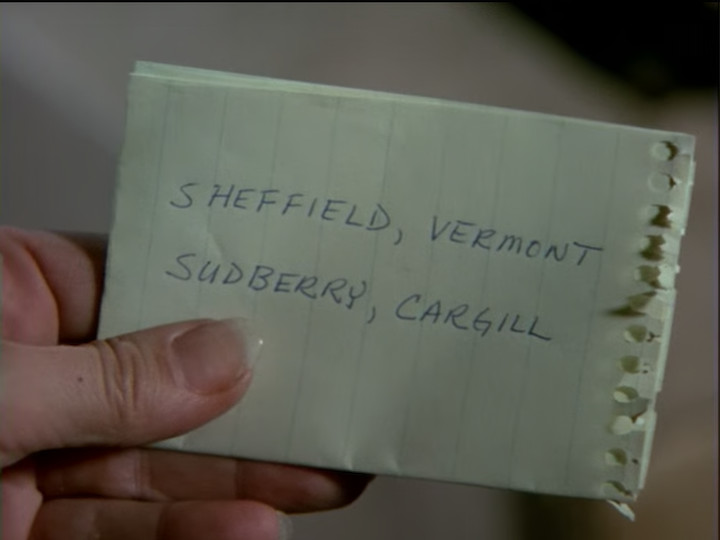

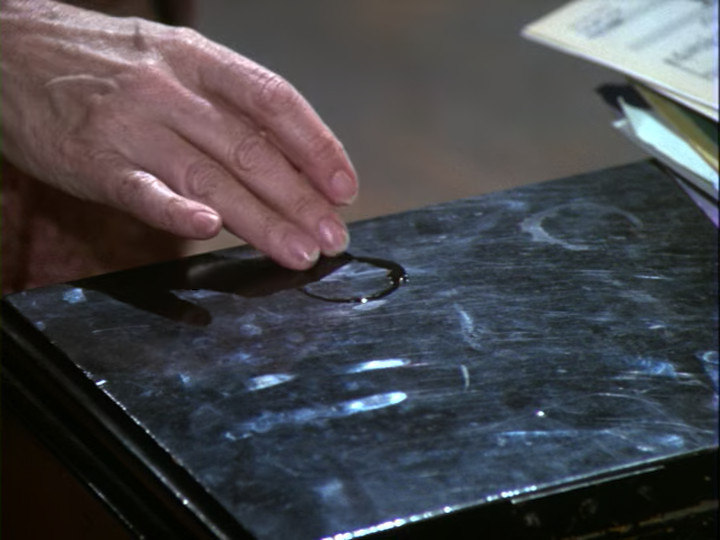

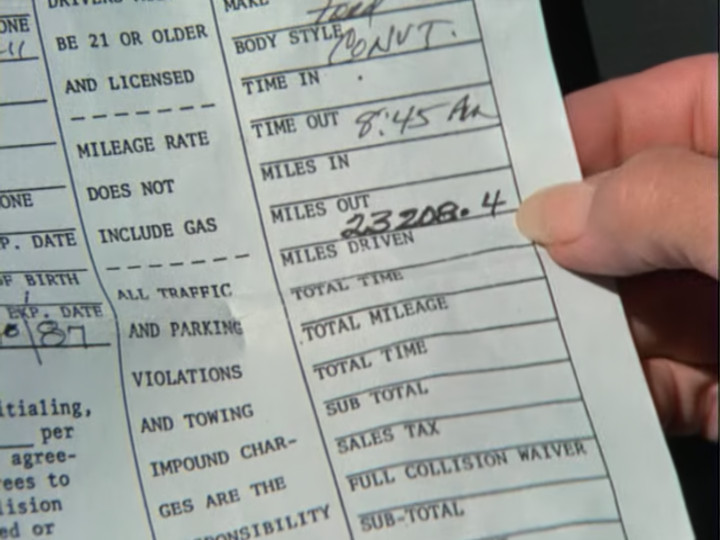

Also, David Marsh gave Seth a scrap that was pried loose from what was left of the guy’s uniform:

The idea that something this old and buried for hundreds of years would be just kept in someone’s pocket and handed around like this is absurd, but I suppose we can take this to just be the prop department saving on making some kind of realistic case for it. And, of course, what possible full sheet of paper could this have been a scrap of?

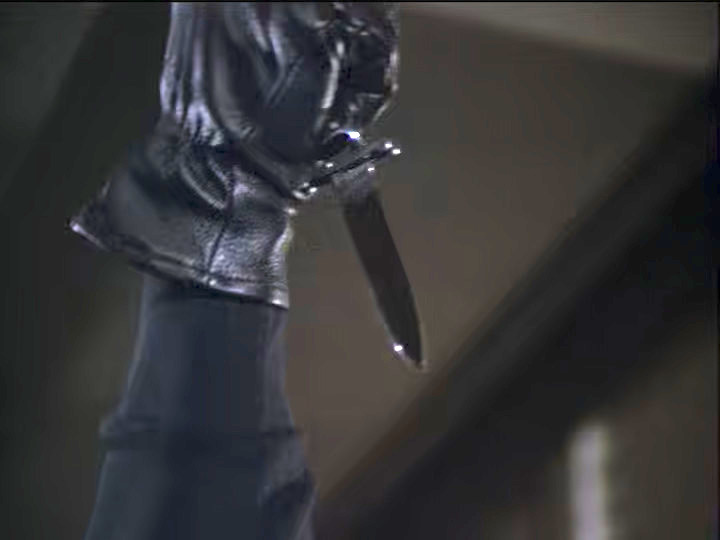

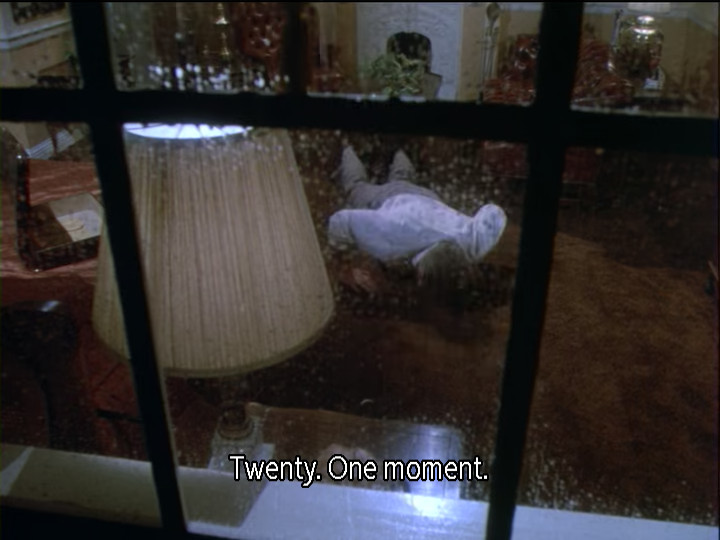

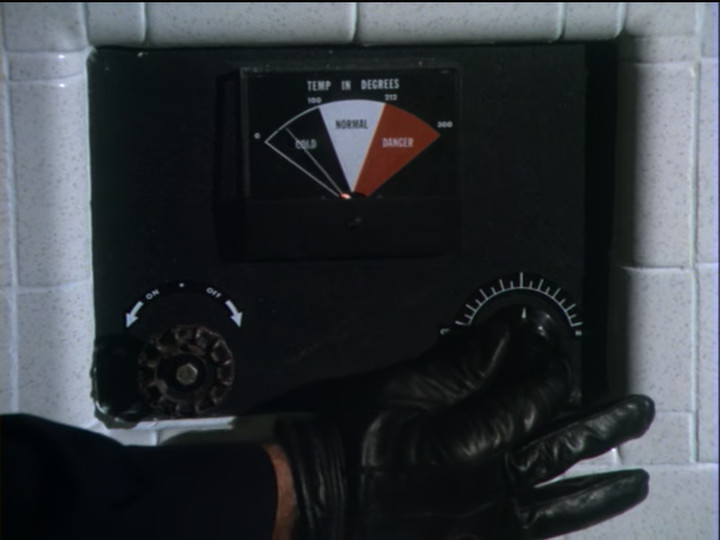

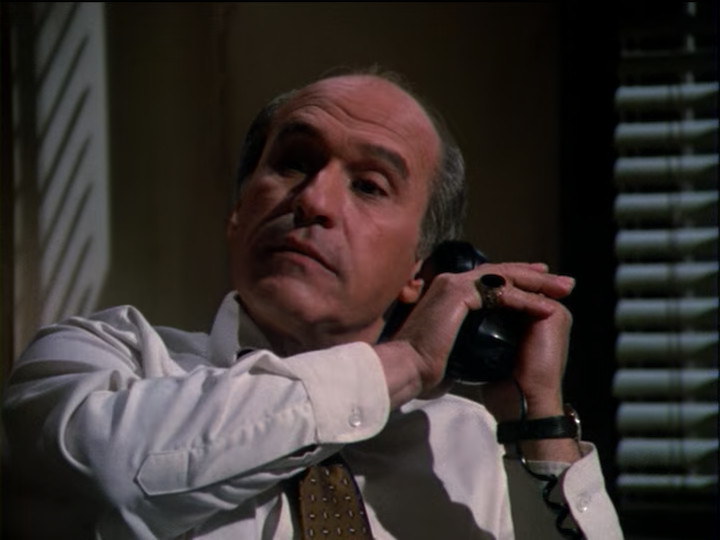

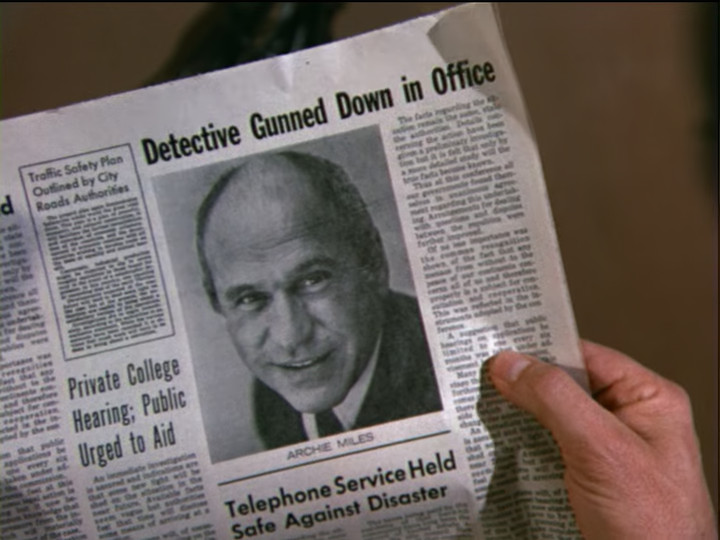

When Seth presents Jessica with a seven-layer cake that they’re going to have for desert, Jessica then gets the inspiration to dig underneath where the skeleton was found for other artifacts. How no one else came up with this idea, I can’t imagine. But it doesn’t much matter, because the actual reason that Jessica and Amos go to the site of the body is to find the murder that this episode is really about:

And on this bombshell, we fade to black and go to commercial.

When we get back from commercial, Seth is giving Amos the results of examining the fresh corpse. Wheatley probably died between 4am and 5am, having been shot at close range. (Also, it came up before the commercial break, but it started raining at 2am, at which point Amos came over and put the tarp over the place where the skeleton had been found and under which Wheatley had been found, to preserve evidence from the skeleton. They made a point of establishing it, so presumably someone is going to know something they shouldn’t about it.)

Amos also notes that Wheatley’s car is here and Kowalski sleeps in a motor home on the premises, so he’ll need to interview him.

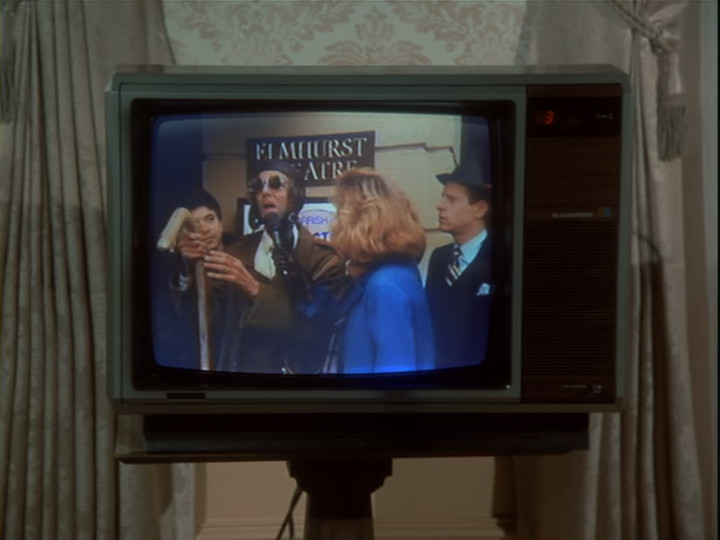

Amos is prevented in finding Kowalski by Del Scott coming up and interviewing him.

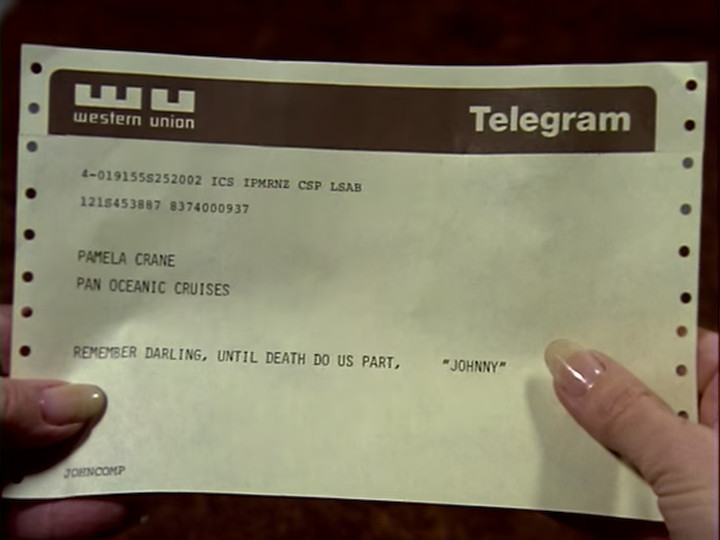

I’d ask why on earth this is in the episode except that her first question explains it:

Would you describe your feelings when you removed the tarp and discovered Mr. Wheatley’s body?

Unless she was the one who put Wheatley under the tarp, she’d have had no way of knowing that it had been under a tarp. It was clearly established that the tarp only showed up a few hours prior to the murder and Jessica and Amos thoroughly uncovered the body when they discovered it, long before Del and her film crew showed up.

In the next scene Jessica ovearhears the lawyer and Kowalski arguing in Kowalski’s trailer with the door open. The lawyer shouts:

You knew what was going on here. You knew the whole scam. Now, I’m the attorney on this corporation. You’ll get not one dime from me.

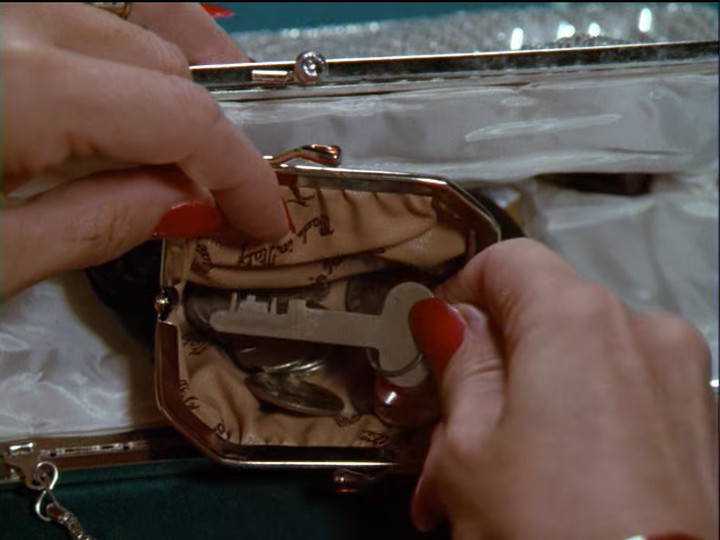

Jessica then discovers Wheatley’s tie clip, close to Kowalski’s trailer. When Amos comes up and asks what she thinks it’s doing here, her guess is that it fell off when Wheatley’s corpse was carried to the excavation. (Jessica thinks he was shot elsewhere and brought to the construction site.)

Later in the day, Jessica goes and examines the construction site and finds that one one the bulldozers has a busted tread, the wheelbarrow next to Kowalski’s trailer has a dirty handle, and Kowalski has a cut on his hand. He then tells her that she’s trespassing and she does an innocent old woman routine, then leaves.

When Jessica gets to town she’s in time to break up some fighting between David Marsh’s son and another kid. Then, as there’s general bickering, FBI Special Agent Fred Keller shows up…

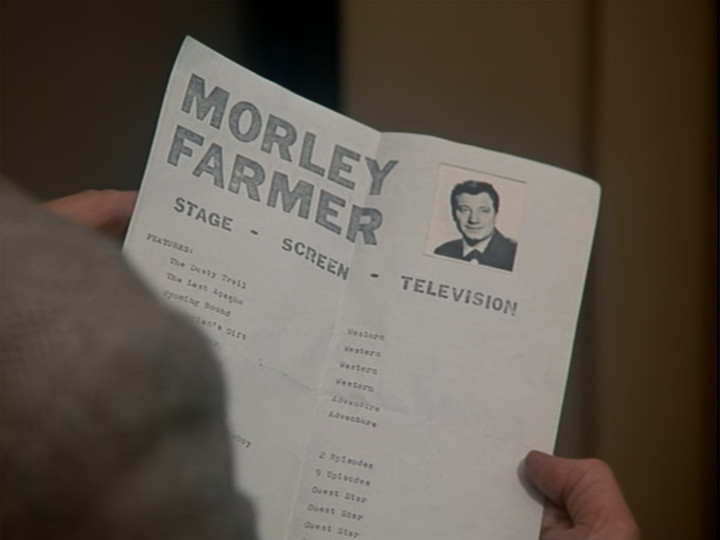

…and arrests David Marsh, noting that his name is actually Daniel Martin. They’ve been after him for seventeen years.

Harry recognizes the name Daniel Martin as a “nutcase Vietnam protester”. Fred explains that, fourteen years ago, Martin bombed a federal courthouse. Amos shows up and tells Agent Keller that David is actually his prisoner, as he’s arresting him for the murder of Henderson Wheatley.

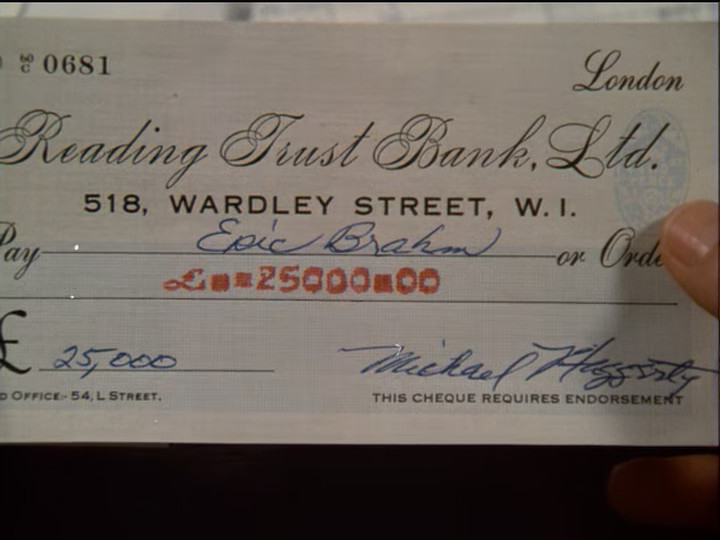

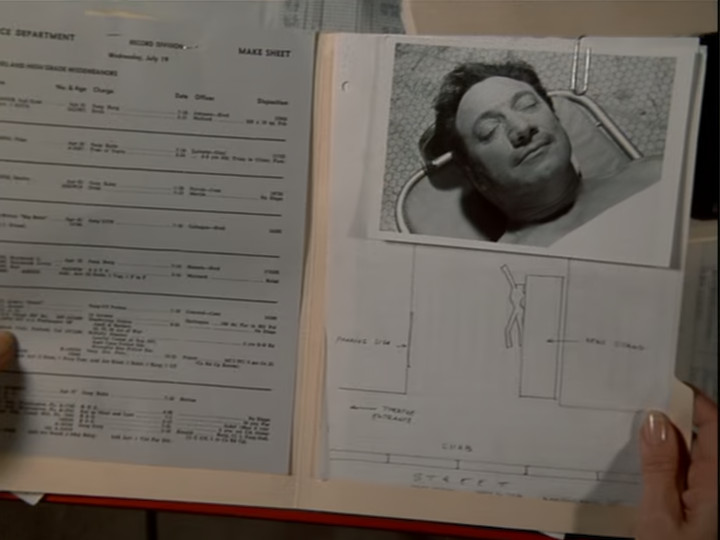

Amos explains his case—he found a note in Wheatley’s office that Wheatley discovered that David had planted the skeleton to slow down construction. David was also seen in the vicinity of the hotel at the same time that the night clerk at the hotel saw Wheatley leave the hotel. He takes David into custody, which Agent Keller isn’t too happy about, but does not stop.

The scene then shifts to Jessica and Seth in Seth’s office when Agent Keller comes in (he had an appointment with Seth). He explains that they didn’t get a chance to fingerprint Daniel Martin, but they were able to obtain his early medical records and he’s hoping that Seth can compare them with his records of David Marsh to make a positive identification. Seth looks at the medical records, but refuses to give Agent Keller a copy of David Marsh’s medical records. Keller is frustrated but assures them that he will get his man, with or without their cooperation.

After he leaves, Seth hints to Jessica that David really is Daniel Martin, and on that bombshell we go to commercial.

When we come back, Jessica is talking with David in jail, where he admits to her that he is Daniel Martin, though he denies being involved in the courthouse bombing. (The day of the courthouse bombing, he was living in Cabot Cove.)

Jessica then goes and finds Kowalski, who has moved his mobile home to a scenic overlook for some reason. Jessica brought him a salve for the cut on his hand and she insists on applying it for him, which for some reason he agrees to.

As they talk, Jessica says that she couldn’t help but notice the shabby state of the construction equipment and that it must have been difficult working for a man with so little regard for his employees.

Kowalski said that it was. Wheatley’s poorly maintained equipment got several friends of his killed. He names two examples: Bobby Scotto in Pittsburgh and Harry Pateki in Detroit (an elevator cable rusted through and dropped him 32 floors).

Of course, it’s hard to not notice that “Scott” and “Scotto” are very similar last names.

Oh, and Wheatley never paid any of the construction workers on this job; unlike before, money now seems to have been in short supply.

Over at the Sheriff’s office, Amos hands Jessica a paper that came over what sounds like a teletype machine and says that Wheatley owed money all over town. Apparently, Amos believes that the lawyer might be responsible, but Jessica doesn’t buy it. Even if the lawyer had a motive, he had no reason to hide the body on the excavation site. Hiding it there felt almost like a symbolic gesture to her.

Amos then reflects on the case and says that it goes to show that if you have something in your past, eventually it will come out. It just doesn’t pay to try and change your name.

At the words, “change your name” Jessica perks up and, presumably, realizes that it might pay to change your name if you’re changing it to sound better as the weather girl on a Pittsburgh TV station. However, Jessica only asks Amos to stop Kowalski from leaving town and to bring him back if he’s already left.

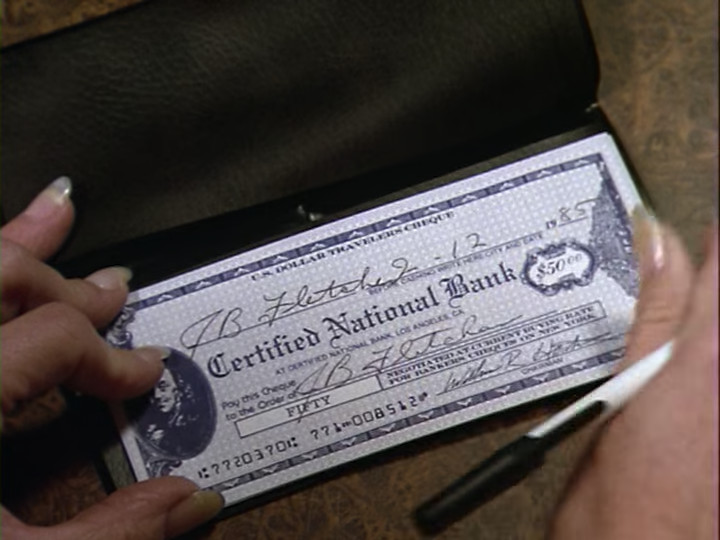

Jessica stops by the library to get some photocopies of news stories (I assume to prove that Daniel Martin alias David Marsh had an alibi for the courthouse bombing). She then calls the hotel and asks for Del Scott’s room. She gets Del and says that she’ll make a statement on Del’s news program. She’ll meet her at the construction site in an hour.

In the interview, she ambushes Del with her relation to Robert Scotto who was killed in Pittsburgh, where Del came from. Del cuts the interview short saying that it has no news value but Jessica keeps going. Jessica phoned the Pittsburgh hall of records and Robert Scotto had a younger sister, named Della Scotto. She then tells Del what happened: at 4am she called Wheatley saying that she had evidence that David Marsh had planted the skeleton. When he let her into his room so she could show him the evidence, she shot him. (How the hotel clerk saw Wheatley leave at 4am if Del killed him in his room, Jessica doesn’t say.)

Del breaks down and says that it is true that her brother died because Wheatley was too cheap to keep his crane in good repair. It broke and dropped four tons of I-beams on her brother. She admits hating him but denies having killed him. Jessica, however, insists that she did. And that after she killed him she put him in the construction site because it seemed symbolic—a grave that he dug for himself.

When the subject of evidence comes up, Jessica points out that Del knew about the tarp despite it being placed on the grave site at 2am and having been removed before her crew got there.

Del then, through tears, says that she tried for years to prove Wheatley’s guilt honestly but every time she got close he bribed witnesses and suppliers. He bought off the people he needed to so that she could never get him. She finishes with, “I’m not proud of what I did, Mrs. Fletcher, but don’t ask me to be sorry.”

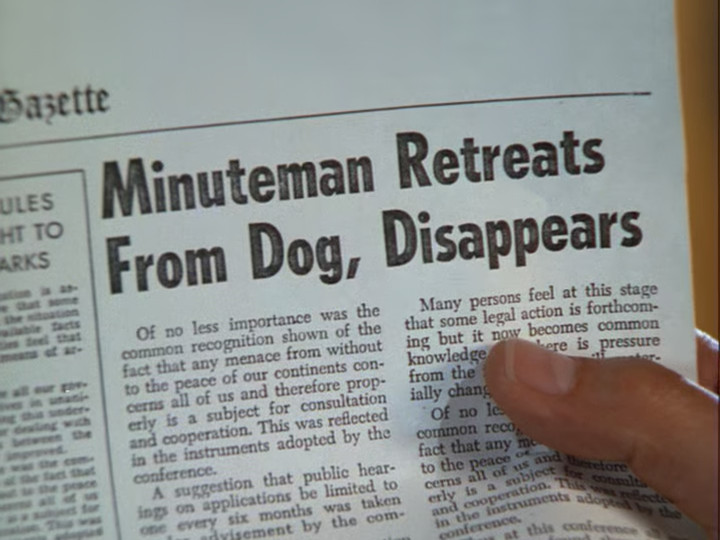

In the next scene Jessica and Seth go to the antique shop, where Agent Keller is arresting the now-free Daniel Martin/David Marsh. Jessica shows Keller a newspaper clipping that places David in Cabot Cove the day before the bombing. Jessica then shows him another clipping about a “Joey Fawcett.”

(It’s interesting that the props people didn’t bother to change the text of the newspaper that they used for this but only made up the headline.)

Jessica says that, clearly, the guy must have fallen and hit his head and died, and at least ten dozen people will swear that Joey Fawcett was actually Daniel Martin.

Agent Keller asks what happened next—the good citizens of Cabot Cove shoveled dirt over him?

Seth replies that there’s no accounting for what folks are here are libel to do.

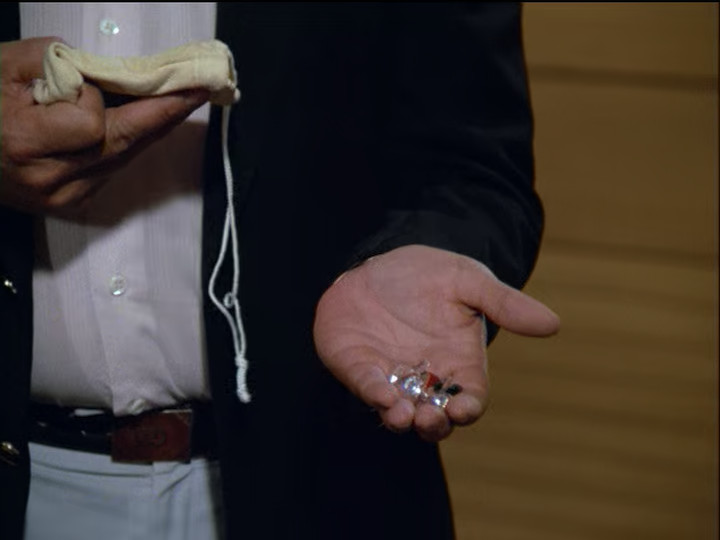

Seth then hands Keller the fractured femur of the skeleton from the dig and invites Keller to compare it with his x-rays of Daniel Martin. Keller does so and it doesn’t match, which Seth tries to explain as the x-rays of Daniel Martin being from before he was fully grown.

Keller then says:

You know, a man must be very special to have people willing to stand up before an agent of the United States Department of Justice and each of them willing to risk charges of perjury, obstruction of justice and harboring a fugitive. Not many men have friends like that.

He then tells David that he (Keller) was wrong and has been pursuing a dead man, and leaves. Before Keller fully gets into his car, he tells Seth that he might want to brush up on his anatomy. The bone he showed Keller was an arm bone, not a leg bone.

After he drives off, Seth remarks that he didn’t think that Keller was that smart.

Seth then says that one good thing has come of this, though. Now that they’ve proved that the bones belong to Daniel Martin, they can put the Joshua Peabody nonsense to rest.

Jessica tells Seth that’s going too far and they laugh and we go to credits.

It was definitely good to be back in Cabot Cove again. Even though it’s a minority of episodes, Cabot Cove keeps Murder, She Wrote grounded. And it’s nice to meet Seth. As much as I did like Claude Akins as Captain Ethan Cragg, Seth is better. And as the town doctor he fits better with murder mysteries, too. This is discussed a bit in a New York Times article from October 27, 1985 which gives a bit of insight into this change:

The weekly arguments between Mr. Fischer and Miss Lansbury come because she wants to expand the character. When the series began, Jessica Fletcher was a substitute schoolteacher riding her bicycle in Cabot Cove, Me., who had written one detective novel. Now, as the famous author of a half-dozen best-sellers, ”She must avoid at all costs being sophisticated or jaded or superior,” says Mr. Fischer.

”She must consort with people of a certain intellectual level,” says Miss Lansbury, who fought ”tooth and nail” against Jessica’s relationship with the owner of a Cabot Cove fishing boat who also served as her handyman, a recurring character last season. ”There’s something wrong with Jessica if she enjoys spending more than 15 minutes a week with that man,” says Miss Lansbury.

The character has been dropped and replaced by a doctor (played by William Windom) with whom Jessica plays chess. Miss Lansbury has also ”fought and won a battle” against the network, which wanted to supply her with a sidekick. ”The whole basis of the show is that Jessica is a middle-aged woman alone,” says Miss Lansbury, ”and the network wanted to have a character joined at the hip who drove a car for me.” She has also resisted a serious romance, though, for a while last season, it seemed as though a different murderer was falling in love with her every week. ”I said no to those slight romantic liaisons. It makes her seem as though she has round heels,” says Miss Lansbury, using a British expression that decribes a woman who tumbles quickly into bed.

Seth being a good change is about the only positive thing I can say for this episode. The problem that most galls me is that it had far more loose ends than tied up ends. The biggest loose end, of course, being how on earth the skeleton—whoever it is—became buried under eight feet of ground on a cliff by the shore. The only way for it to have happened would have been for someone to have buried him quite remarkably deep for a grave, because dirt does not accumulate at anything like the rate of four feet per century, to say nothing of half a foot per year if this really was from a reenactor. You can easily tell this by going to a cemetery with two hundred year old tombstones and noting that they’re not buried under six feet of dirt.

And how on earth was this skeleton uncovered in a way that anyone noticed? A large, deep cut like this would be done with earth moving equipment. That doesn’t lend itself to noticing dirt-colored bones, even if by pure luck you happened to excavate right above the skeleton, exposing it, rather than picking it up in the excavator’s scoop.

And then there’s the way that the identity of the skeleton is never decided and, in fact, just dropped. The skeleton is hugely important to the episode; it drives most of what happens. And, after a few initial snippets about a British musket near to it and a scrap of paper that is oddly durable, we get nothing more. Everyone just stops caring about it.

I also don’t know why David Marsh/Daniel Martin is supposed to be a sympathetic character. All we know about him is that he’s against an absurdly large hotel in a place that would have great trouble filling it to a quarter capacity, leads a protest that Jessica is sympathetic to though it’s not clear why she should be, is always causing trouble in Cabot Cove, and fifteen years ago he did a bunch of “nutty” Vietnam war protest stuff. Oh, and his son gets into an awful lot of fights. I’m not seeing what we’re supposed to like about this guy. Are we even sure he didn’t plant the skeleton? He certainly was the person in Cabot Cove with the most access to things that can be planted to lend credibility to the “find” and we’ve established that he isn’t scrupulously honest. (Just as a side note: how would tiny little Cabot Cove support an antiques dealership?)

We also get a villain in the episode with all of the sophistication and nuance of Luten Plunder from Captain Planet. So far as I can tell, Henderson Wheatley cheats because he would rather be corrupt than honest. Are we really to believe that it costs more to settle a worker’s death, repair a broken crane, clean up dropped I-beams, suffer delays during which people get paid but work doesn’t get done, and bribe all manner of people to cover it up than it would be to just repair the crane’s cable before it breaks? People do skimp on necessary maintenance when they’re short of money and, instead of doing the things that will reliably make them more money, hope that things will work out until they have the money to cover the repairs. People don’t skimp on necessary when they’re rich because paying for maintenance is much cheaper than paying for repairs. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure to the rich as well as to the poor. In fact, one of the ironic things about poverty is that it’s more expensive to be poor because the rich can avoid all sorts of major expenses by paying much smaller ones to prevent the big expenses from being necessary. All of which makes the character of Wheatley being so rich he can get away with anything not make any sense in the episode.

Especially because it’s actually a plot point that he isn’t so rich. They very clearly established that money was in short supply on this job. They even went so far as to have the lawyer angrily yell at Kowalski that he (Kowalski) knew what the scam was when he started the job. But once Kowalski shares the useful information of “Robert Scotto” having been killed through Wheatley’s negligence, this is entirely dropped.

Overall, this episode is a mess. We don’t get our body until right before the mid-point commercial break, the victim is a cardboard cutout of evil, the supposedly sympathetic characters aren’t sympathetic, and most of the interesting plot threads are dropped for no reason. Heck, we even get unambiguous evidence of who the killer is less than a minute and thirty seconds (not counting the commercial break) from finding the body, making the rest of the investigation obviously pointless.

Oh well. Next week we’re in New York City for Murder in the Afternoon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.