On the thirty first day of March in the year of our Lord 1985 the nineteenth episode of Murder, She Wrote aired. Set in Texas, it’s titled Armed Response. (Last week’s episode was Murder Takes the Bus.)

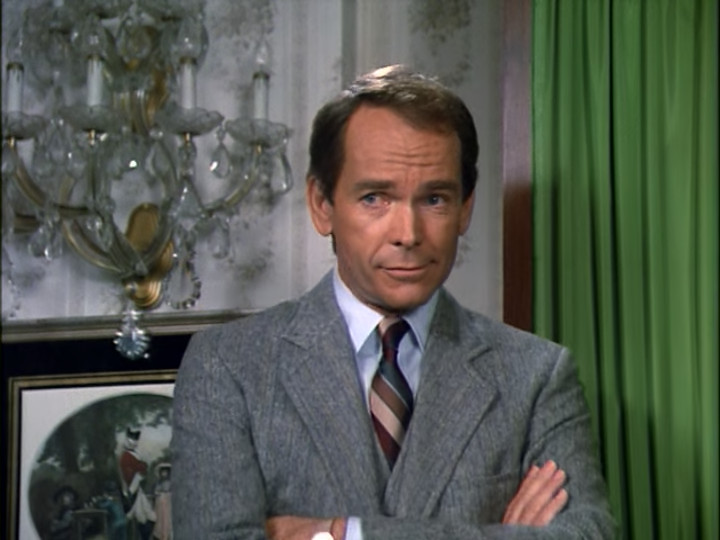

It opens with a voiceover of someone talking in a thick Texan accent telling the person on the other end of the phone to go to the jail and find someone. We then get a view of him:

His name is Milton Porter and I’d say that he’s a walking stereotype of a rich, predatory lawyer… except he’s sitting down. They lay it on thick, but the specifics don’t matter. He’s really just a convenience to get the plot started.

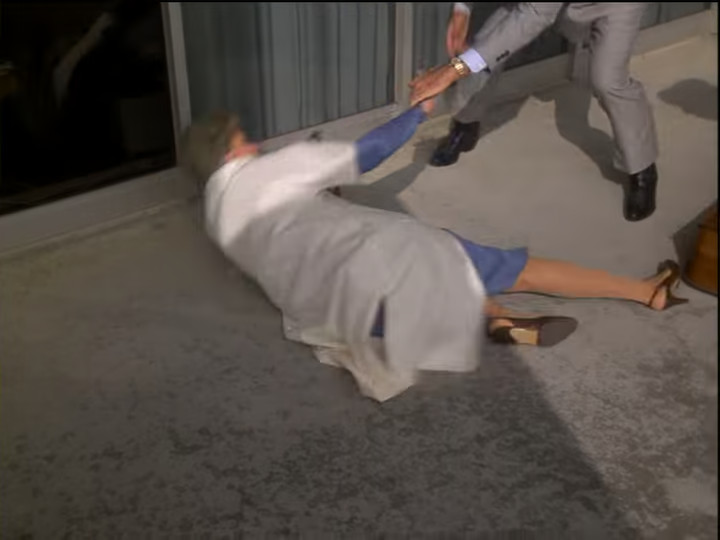

He meets Jessica at the airport. She’s come to town to testify on behalf of one of his clients. On their way to his car, some kids run into an airport employee who falls into Jessica, knocking her down. Here I have to pause to show the stunt man playing Jessica:

“Jessica” stumbles, then loses her footing, falling to the ground:

When she’s helped back up her left leg doesn’t feel too steady, so Mr. Porter packs her off into his limousine saying that he’ll take her to the fanciest hospital in Texas and promising that he’ll be able to win at least a $50,000 settlement from the airport for gross negligence. The first half of that is the important part…

…because that’s how we get to the Samuel Garver institute, where the episode takes place.

Then we meet Dr. Sam Garver and Dr. Ellison. (Dr. Garver is the older man, in front.)

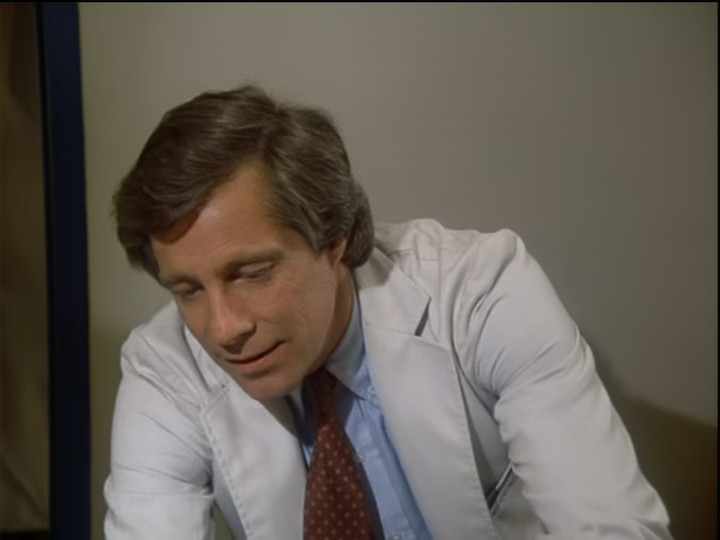

And yes, Dr. Ellison is played by Martin Kove, who played John Kreese, owner and sensei of the karate dojo Cobra Kai, in The Karate Kid (the year before).

Anyway, Dr. Garver tells Jessica that she has a small fracture in the fifth metatarsal, but the good news is that she can be fitted with a walking cast. I’m a bit suspicious of this diagnosis since the metatarsal is in the foot and Jessica didn’t put any great weight or sudden impact on her foot. I’d have expected, if anything, some kind of torsional injury to her ankle. That said, I don’t think that this is supposed to make us suspicious of the doctors; it’s probably just medical lingo thrown in to make it sound doctory.

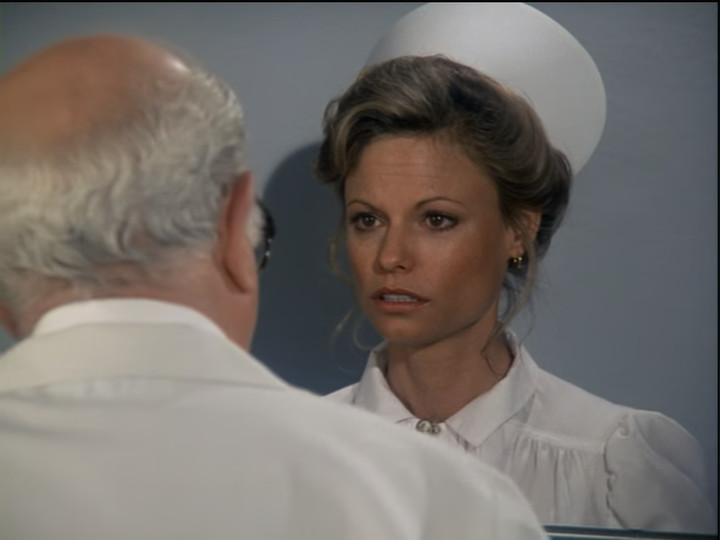

After some banter, Dr. Garver goes to leave and the nurse—her name is Jennie Wells—stops him and says that she wants to discuss a patient on her ward—Mr. Ogden.

Ah, the days before HIPAA, when you can just discuss people’s medical conditions in front of complete strangers. Anyway, Dr. Garver tells her that there’s nothing wrong with Barney, and she says nothing that would show up on a chart, and he replies, very coldly and sternly, “How nice that we agree.”

After this, Dr. Ellison puts the cast on Jessica:

It seems to be a plaster cast, which is a little odd since they had fiberglass casts at the time and one would expect them to use more modern technology in such a high-end hospital. Anyway, he says that to be safe, they want her stay overnight. Wanting her to stay overnight for observation for a small hairline fracture strongly suggests that they bilk patients through unnecessary procedures, but Jessica seems to think that this makes sense.

She then identifies his accent as being from Chicago. She has a cousin who sounds exactly like him and was born and bred on the north side. Dr. Ellison sighs and replies that he’s from the south side. (The south side of chicago is poorer and more crime-ridden than is the north side.)

We then meet another patient:

Her name is Mrs. Sadie Winthrop and she’s loud and gregarious and loud. Also talkative.

We then meet the head nurse:

Her name is Marge Horton. She and Jessica chat about the weather in Texas vs. Maine, then Jessica tries to present her medical insurance card but Miss Horton says that they don’t deal with insurance here. (The lawyer stereotype is taking care of it and he expects the airport to take care of it.)

They then run into Dr. Wes Kenyon in the hallway:

He takes a look at the cast and sounds concerned when he hears that Dr. Ellison applied it, though he can find no fault with it.

After he leaves and Jessica is wheeled to her room, she asks about his reaction and Nurse Wells tells her that Dr. Garver has a habit of destroying the reputation of anyone he fires and there’s a rumor that he’s bringing in a replacement for one of Ellison or Kenyon.

Later that night, at a party at Dr. Garver’s house, we witness a rich hypochondriac who doesn’t get along with her husband squabble with him in front of Dr. Garver and Dr. Kenyon.

Dr. Garver excuses himself from this because of a telephone call which turns out to be from Nurse Wells, who says that she needs his authorization for some tests. He curtly answers “no” and tells her to never call him at his home again.

When he gets back from that, Dr. Kenyon tells Garver that he’s leaving as he’s on duty in 45 minutes. When he thanks Garver for inviting him, Garver replies that he’s inviting Ellison for brunch on Sunday, since he can’t play favorites.

Back at the hospital, Jessica meets Barney Ogden after unsuccessfully trying to buy something at one of the vending machines.

It seems a bit strange that she should have to buy something at a vending machine in a luxury hotel, but I suppose she needed to meet the other patients somehow. They actually lampshade this when Jessica goes to get change at the nurse’s station and Nurse Horton tells her that she shouldn’t be up and about and that they would have brought her tea. Jessica says that she didn’t want to trouble them because they’ve got too many people who are really sick. (I’m not sure that this is true.)

Just as a side note, Jessica is walking around on crutches with the leg in the cast held off the ground, despite supposedly being put in a walking cast. I doubt that’s supposed to mean anything, but it is strange.

Anyway, Doctors Ellison and Kenyon walk into the nurse’s area, arguing loudly. Kenyon then notices all of the people looking at them and tells Ellison that if he wants to talk they should do it in private. They then walk into an office and proceed to argue even louder. The walls and door are, apparently, quite thin, because everyone can still hear them.

We then fade to an establishing shot of Dr. Garver’s house, then we cut to an establishing shot of a security company, from which the episode derives its name:

I can’t help but also show what the interior of the security office looks like:

I can’t imagine that this security office is even slightly realistic, but it is very evocative.

Anyway, the alarm for Dr. Garver’s house goes off and the guard sitting at the computer places the olbigatory phone call. When no one answers, the guard who was over by the map says that he’ll check it out. On his way to Dr. Garver’s house he comes to a three-way stop sign and sees Nurse Wells stopped at the stop sign, on the street to Dr. Garver’s place as if she just came from there:

This is quite suspicious, of course, meaning that Nurse Wells is definitely innocent.

When the guard gets to Dr. Garver’s house he runs in and discovers Dr. Garver, dead:

The camera zooms in on the body in the pool, then we fade to black and go to commercial.

Had you been watching back in 1985, you might have seen a commercial like this:

When we get back from commercial we get an establishing shot of the Garver Institute, then we move inside where Jenny serves Jessica Dr. Garver’s “world-famous” apple flapjacks. After which Sadie Winthrop arrives. She asks for flapjacks and coffee. Jennie replies that she can have flapjacks but no coffee. Dr. Kenyon got the word from Dr. Sam that she’s been much too active. Until further notice, she’s being put on carrot juice. (Sadie does not like the look of the carrot juice.)

Barney Ogden then walks up and apologizes to Jessica about having been rude to her the night before. Jessica Demurs and Mrs. Winthrop tries to give him her carrot juice.

They then hear a scream and Nurse Horton runs through. Dr. Kenyon follows her but doesn’t catch up to her. When Nurse Wells asks what’s wrong, Dr. Kenyon tells her that Dr. Sam is dead. Murdered last night. The radio report he heard said that there was the possibility of someone having broken in.

When Jessica returns to her room, she meets Lt. Ray Jenkins.

He’s the homicide detective in charge of the case and he’d like Jessica’s help. He’s not sure that the killer was just an intruder. One reason why is that the body might have been moved to the fish pool since the bullet entered at a forty-five degree angle which means that he was either sitting down or killed by an NBA center.

Lt. Jenkins has a good-ol-boy, shucks-ma’am style of speaking, but you do get the sense that it’s a Columbo-style attempt to be underestimated, not a lack of intelligence. When Jessica demurs, he tells her that he just transferred in from a rough neighborhood and doesn’t know how to talk to fancy folk like the ones at the hospital.

Jessica agrees and suggests that they start at the scene of the crime. Lt. Jenkins replies that it’s only five minutes away and the scene shifts to Dr. Garver’s house. There, he explains how the alarm works. I’m actually surprised by the amount of detail given; by the mid 1980s home security systems were far from universal but also far from unheard-of. And we already saw all the important parts anyway.

We do get some times, though. The alarm went off at 11:06pm and the officer arrived at 11:15pm. A next door neighbor thought that she heard a car backfiring a few minutes into the 11:00 news. (Backfiring, which is the rapid burning of fuel in the exhaust system, was more common in cars in the days before computer-controlled fuel injection and catalytic converters; older systems of mixing the fuel and air could easily lead to over-rich fuel-air mixtures and incomplete burning which allowed for the conditions for it to ignite in the exhaust. These explosions sounded somewhat like gun shots.)

The only other clue he has to tell Jessica about is that they found Garver’s keys by the front door. When Jessica asked what they were doing here Lt Jenkins replies that he must have dropped them. When Jessica asks why, because he was already in the house. Lt. Jenkins smiles…

…then asks her, very dryly, “Got any ideas?” His manner strongly suggests that he knew perfectly well that it makes no sense that Garver’s keys were outside of his door and we’ve come to the part why he asked Jessica to come—that is, to the hard part.

Jessica chuckles as she realizes that she can’t get away with doing only the easy part then says that she’s sorry but she doesn’t have a glimmer of an idea.

Back at the hospital, Jessica is met by Dr. Kenyon, who tells her that they were just about to send a search party out for her. She says that her leg is acting up and asks for a wheelchair. Dr. Kenyon obliges and personally pushes it. On the way back to her room, he tells her that he wasn’t surprised by Dr. Garver’s death—Garver had a lot of enemies. In ensuing conversation, Dr. Kenyon says that it was generally understood that he was next in line to run the hospital. Dr. Garver didn’t say so explicitly, but the signs were clear.

Jessica brings up Dr. Ellison and Kenyon says that he’s never liked Ellison. There’s something dangerous about him—a street kid who couldn’t leave the streets behind. He also mentions that Dr. Ellison keeps a gun in his car. I’m not sure that this would seem that out of the ordinary in Texas, but Hollywood writers generally know nothing besides Hollywood. And, to be fair, Dr. Kenyon doesn’t have a Texan accent.

When Jessica asks if Kenyon is trying to suggest that Ellison killed Garver, Kenyon replies that he’s a doctor, not a policeman, and excuses himself. (In other words: yes.)

Jessica then drops in on Barney Ogden. She’s clearly curious about what’s wrong with him. Then Mrs. Winthrop drops in and tries to bully him into being happy. When she asks if he’s only here because he likes it and doesn’t he have someplace else he’d rather be, he replies that no, he doesn’t. His wife died nine years ago and he never had any children. All he’s got is a nephew who only wants his money and a few cousins in Alaska.

After this scene winds down, Jessica spots Nurse Wells being escorted into a police car. In the lobby Lt. Jenkins is thanking Nurse Horton for her help when Jessica arrives. Ray explains that she’s been taken in for questioning since the security guard spotted her about three blocks away from Dr. Garver’s house. When Jessica says that there must be some mistake, Nurse Horton tells her that one of her nurses saw Nurse Wells sneaking out the back way at around 11:00.

And on this bombshell we fade to black and go to commercial.

When we come back from commercial, the Lawyer stereotype shows up at the hospital in response to a summons from Jessica. She wants him to rescue Nurse Wells. After some back and forth, we get a bit of exposition—from an off-screen conversation that Jessica had with Nurse Wells. She did leave the hospital but only to talk to Dr. Garver. She arrived at 11:10 and there was no answer to her knock. (The lawyer stereotype balks at taking the case until Jessica threatens to not testify on behalf of his client that she’s in town to testify for.)

In the next scene Lt. Jenkins is calling Jessica from a payphone to let her know that Nurse Wells has been released. Jessica is delighted to hear this then says that she’d like another look at the crime scene.

As Jessica is waiting for Lt. Jenkins to pick her up, Dr. Ellison runs into her. She learns from him that the trustees of the hospital have named him and Dr. Kenyon to jointly run the hospital on an interim basis. She also finds out that Ellison was sure that the new doctor was to replace Kenyon. Garver didn’t like Ellison’s family tree, but he knew a good doctor when he saw one.

On the way over to Dr. Garver’s house, Lt. Jenkins tells Jessica that shortly before Dr. Garver died he called the hospital and left a message on Nurse Horton’s answering machine. He has the tape with him and plays it for Jessica.

Marge, it’s me. A couple of things for the morning. I’ll be in late. I want Peabody up and walkin’ no matter how much he complains. Second, get Sadie Winthrop on carrot juice. She’s too hyperactive for her own good. One other thing. That Nurse Wells is gettin’ to be a real problem—startin’ to think she’s a doctor. Now, find some excuse to get rid of her. Now I’m goin’ to bed. See you tomorrow. You take care now.

I really like the establishing shot of Dr. Garver’s house, by the way:

He was a rich man.

Lt. Jenkins tells Jessica that they already had Nurse Wells’ opportunity and now they have her motive. When Jessica says that this is rubbish, he asks why she’s defending Nurse Wells out of pure guesswork. Jessica replies that it’s called reading people.

This is interesting because Jessica deciding that someone is definitely innocent is a common occurrence in Murder, She Wrote. Jessica has the writers on her side so she’s always right, but it’s often hard to see what she’s going on other than the episode portraying the character as sympathetic.

Anyway, they go inside. Jessica looks around and says that the tape contradicts Jenkins’ theory that Garver was attacked while he was getting back from a walk. If he was going to bed, he must have been killed inside the house, which means that his body in the pool in the foyer was staged.

Inside they discuss some possibilities, then discuss the question of why the body was dragged out to the fish pool. Jessica says that the pond was heated because of the fish, which makes the time of death uncertain. Lt. Jenkins wonders at this because the neighbor heard the shot at 11:05 and the guard arrived at 11:16, so the time of death doesn’t seem very uncertain. Jessica then asks if he has any blanks for his gun.

They then stage the experiment where Jessica visits the neighbor while Lt. Jenkins fires the gun. They hear the shot and the neighbor says that it’s exactly like what she heard the other night. (There’s an annoying comedy bit where she’s sure that this isn’t really police business and there’s a hidden camera where she’s supposed to taste-test coffee or something.) The only thing is, Jenkins didn’t fire one shot, he fired two. The first inside the house, the second outside the house, the latter being meant to obscure the time of death.

That night at the hospital, Jessica visits Nurse Horton. After pumping her a bit, she reveals that she and Dr. Garver and an intimate relationship. She narrates how the day she learned of Garver’s death went. It’s sweet, but clearly here to give us the salient fact that she didn’t play the answering machine tape until later in the day. Then she’s interrupted by a nurse who tells her that the police are searching the locker room with a search warrant.

In the locker room Lt. Jenkins is there with some uniformed police offers and explains that he received an anonymous tip that the murder weapon was in Nurse Wells’ locker.

They find a gun—which Nurse Wells protests is not hers—in Jennie’s locker so Jenkins directs the officers to arrest and book Nurse Wells.

When Jessica tells him that he’s making a dreadful error, Jenkins replies that they have motive, opportunity, and now means. He says that they’ll let ballistics decide if it’s the murder weapon.

Jessica retorts, “Well of course it’s the murder weapon. Who ever heard of framing someone with the wrong gun?”

And on that bombshell we fade to black and go to commercial.

When we come back from commercial we’re at the lawyer Stereotype’s office. Jessica is telling him that the murder weapon was obviously planted in Jennie’s locker when Dr. Kenyon comes in. He informs the lawyer stereotype that the hospital stands behind Nurse Wells completely and that they will be responsible for any legal fees involved.

Back at the hospital, Jessica runs into Barney Ogden and Sadie Winthrop who are playing gin rummy together and clearly enjoying each other’s company. Barney is in remarkably good spirits as he wins the hand as Jessica walks up. A minute later Sadie gets carrot juice and this puts Jessica in mind of something. She goes off and calls Lt. Jenkins.

We then cut to Lt. Jenkins in front of the nurse’s station asking Dr. Ellison if the gun is his. Ellison denies even owning a gun, but Kenyon contradicts this. Ellison replies that he told Kenyon a lot of things, many of which were not true.

Jessica then barges in and begins angrily asking Lt. Jenkins what is doing. After a bit of bickering, she asks to speak to him privately and then goes into the same room that Ellison and Kenyon had their fight in. Lt. Jenkins follows her and the two begin yelling at each other.

Various people in the lobby comment on the fight, then Jessica walks up behind them and says hello, then calls out to the Lt. that he can come out now. Which he does, holding a boombox which is still playing their argument.

We cut to Dr. Ellison and Dr. Kenyon looking like they’ve been caught, but smart enough to not say anything. Then Jessica asks Nurse Horton whether they witnessed a similar scene two nights ago when Dr. Garver was killed. (She says yes, of course, since we obviously did.)

Jessica then goes on to produce the evidence: Dr. Kenyon switched Sadie Winthrop to carrot juice for breakfast on Dr. Garver’s orders but Nurse Horton didn’t play that tape until lunchtime. There was only one way he could have known about those orders: if he had still been at Dr. Garver’s house when Dr. Garver dictated them onto Nurse Horton’s answering machine. He must have killed Dr. Garver right after the phone call, but before 11:00. Then someone had to go to Dr. Garver’s house and fire the gun outside then set off the alarm during the very public argument behind closed doors.

Ellison breaks down and explains what happened. It was Kenyon’s idea but he went along with it. He then narrates what happened, which is basically what we already knew. Kenyon stayed behind and shot garver, then they staged the argument and Ellison went back and opened the door, setting off the alarm, and fired a shot into the air. He came in the same way he left.

The next day Jessica is walking to a car without crutches, talking with Nurse Wells. Jennie thanks her lucky stars that Jessica was here to help her and asks why they did it . Jessica says that it was simple survival. One was about to replaced and his career destroyed, but they didn’t know which, so they decided to put aside their differences and eliminate the threat that faced both of them. They only decided to pin the murder on Jennie after the fact. Jessica wishes Jennie well and then asks her to write and let her know how the love birds (Sadie and Barney) are doing.

As the final thing in the episode, the lawyer stereotype pulls up. He banters with Jessica and we learn that he’s taken on the case of defending Kenyon and Ellison. He wishes her farewell and as she gets into her taxi, she tells him, “See you in court!”

And we go to credits.

This episode had some really fun things in it and some really stupid things in it. Let’s start with the fun things.

The basic mystery was fun. A murder in a big, empty house with apparently tight timeline is always interesting. There were clues which weren’t obvious that turned out to be meaningful, such as the body being in the fish pool and the keys being found outside the house. The apparent alibi of the two most likely suspects was also interesting.

I also really liked Lt. Jenkins. I think that the character fell a bit short of his promise but he felt like a Columbo-like character, which is very interesting to pair with Jessica. Jessica is used to estimating the competence of the police to be very low—accurately, most of the time—so that part fits. Seeing her surprise, and the contrast of detective styles, was interesting. I wish that they had leaned into this more; it would have been fun to see Jessica having a little bit of competition and rising to the occasion.

Unfortunately, that’s about it for the stuff I liked.

I really disliked the lawyer stereotype. All of his scenes should have been replaced by more characterization of actual characters. (This is a knock against the writers, not the actor—he did a fine job with what he was given to work with.)

I also think that the character of Nurse Jennie Wells was a big mistake. Admittedly, she’s a pretty, young woman in trouble so she is automatically sympathetic, but this has to work against the character as she was written. She’s meant to be the kind of medical practitioner who cares and goes the extra mile, and we’re supposed to approve of her for it. In the end of the episode she asks Jessica how she can thank Jessica for saving her and Jessica replies she can thank Jessica by continuing in her career because medicine can use a lot more like her. The thing is, it really couldn’t. Nurse Wells never actually helps anybody—she just gets in the way of the people who are. The episode even spends several minutes showing us conclusively that Dr. Garver was right and there was nothing wrong with Barney Ogden. He didn’t need treatment, he just needed a friend. Running the tests on him that Nurse Wells wanted to run would have turned up nothing useful and created the possibility of misleading results that led to unnecessary treatment.

Moreover, calling the head doctor at home, then skipping on her shift and driving over to his house in order to talk him into tests was highly inappropriate. Doctors go off duty for several reasons. For one, they’re human beings and deserve time off. For another, they need to rest so that they can do a good job when they’re on duty. People who are burned out because they never rest don’t do a good job. It’s also the case that there is an on-duty doctor at a hospital who can handle any emergencies which come up. There’s no way to need emergency tests at 10pm at night and have to call an off-duty doctor rather than finding the on-call doctor and asking him. Even worse than this, a nurse doesn’t order tests and require someone’s permission to do it; the doctor is the one who orders tests. This is because doctors have trained extensively under supervision from other doctors in order to have a sense of what’s needed and what isn’t and the complex interplay of many different things. That’s not to say that doctors are always right and there’s nothing that would prevent a nurse from extensive study and gaining this knowledge on the side, but if she did this, it’s only reasonable to take the time to prove it to people before she asks them to trust her. But we’re given no reasons to believe that Nurse Wells has done any of this training and we are given reasons to believe that she hasn’t. The only beneficial things we actually see her do anyone are to push Jessica around in a wheelchair and serve pancakes.

Frankly, Dr. Garver was right to want to get rid of her.

Probably the worst thing about this episode was that the episode hinged on carrot juice replacing coffee. Everything about this plot point was stupid. First off, the order to put Sadie Winthrop on carrot juice makes no sense. She has a broken leg and she’s a fiesty, energetic woman who’s bored and looking for stimulation. She’s not active because she has coffee. She’s active because that’s the kind of person she is. Putting her on carrot juice will just make her more bored and make her look for more trouble to liven up her day. And it’s not even a problem if she is active—she’s got a broken leg that’s in a cast. As long as she’s not whacking things with her cast as hard as possible, she’ll be fine.

But even if we accept this, the next step was that Dr. Kenyon, who was hiding out at Dr. Garver’s house, listened to the message he left on Nurse Horton’s answering machine carefully enough to hear the instructions, then after murdering Dr. Garver, he still dutifully carried out Dr. Garver’s orders about the carrot juice when he knew that Dr. Garver had left them on an answering machine for someone else! He wouldn’t have done that if he’d just stayed late at the party because he lost his favorite tie-pin, because people don’t ordinarily rush to implement orders that were given to someone else. But after committing a daring murder, he decided that ridiculous medical instructions are the better part of valor and put the carrot juice order in himself, lest the patient have an extra cup of coffee in the morning before Nurse Horton heard the message and put the order into effect. As unscrupulous as he was to plan a murder instead of just securing another job before Dr. Garver could fire him, he couldn’t bear the thought of an excitable patient—moreover, a patient with a broken leg and not something sensitive to caffeine like a heart condition—having one extra cup of coffee. And if it weren’t for that level of dedication to his patients, he and Doctor Ellison would never have been caught!

This is almost Encyclopedia Brown levels of “you made one mistake.”

(To be clear, I like Encyclopedia Brown stories quite a lot; but they are highly simplified for their intended audience of children and mostly don’t stand up to exacting scrutiny because they rightly prioritize intelligibility to children over verisimilitude.)

Oh, well. Next week we’re in California for Murder At The Oasis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.